by Jacob Heybey, HIST 288, Spring 2015

On July 13, 1858, the New York Times commented, “Illinois is from this time forward, until the Senatorial question shall be decided, the most interesting political battle-ground in the Union.”[1] Democratic Senator Stephen A. Douglas had just announced the start of his reelection campaign and the contest between Douglas and his Republican challenger, Abraham Lincoln, held national interest. For Douglas, a well-known and respected Senator, the election promised to be one of the biggest political challenges of his career. Having recently split with Democratic President James Buchanan and his supporters over the admission of Kansas to the Union, Douglas not only had to deal with his opponent, but also had to defend himself from the administration’s supporters.

Seeking to capitalize on the split between Douglas and his party, the Illinois Republican convention took the unprecedented step of officially endorsing Abraham Lincoln as their “first and only choice” for Senate on June 16, 1858.[2] The ensuing election was hotly contested and both candidates heavily canvassed the state. By himself, Lincoln traveled 4300 miles and gave 63 notable speeches, plus numerous smaller ones. Douglas made a comparable number of speeches and covered even more ground.[3] “Such exertions for a Senate race” writes Richard Brookhiser, “were unheard of in American politics.”[4]

In late July, encouraged by prominent Republicans to put pressure on Douglas, Lincoln proposed a series of debates with the incumbent. Douglas agreed, on the condition that he be allowed to set the times, places, and format of the debates. He proposed (and Lincoln accepted) seven “joint discussions” starting in late August and ending in October, each with the same format; one candidate delivered an hour long address, the other was allowed an hour and a half to reply, and then the first candidate concluded the debate with a short half hour long speech.[5]

The third debate was held on Sep. 15, in Jonesboro, Illinois, in the southernmost part of the state. In comparison to the first two debates, held in Ottawa and Freeport, attendance was sparse, tallying approximately 1500 spectators, as opposed to the large crowds that had gathered for the previous debates. This was in part because Jonesboro was in one of the poorest, most unpopulated, and heavily Democratic regions of the state; Allen Guelzo mentions “not only were the Buchanan loyalists undisposed to show up for Douglas’s benefit, but the Illinois State Fair had opened the day before… and that pulled still more of Union County’s thin population away from the debate.”[6] Lincoln spoke second at Jonesboro, using the vast majority of his time to directly answer Douglas’s opening speech. (Lincoln’s full speech here, featured excerpt here)

Overall Summary

Lincoln opened on a conciliatory note; he declared that he had no disagreement with Douglas on the basic doctrine of states’ rights. He then quickly shifted to discussing Douglas’s views on slavery from a historical perspective, claiming that Douglas had strayed from the ideas of the Founders on slavery, whereas Lincoln was true to their original intent. This section comprises the featured fragment, which is analyzed in detail below.

As in any political campaign, conspiracy charges abounded. Douglas had accused Lincoln of conspiring with Democrat turned Republican Senator Lyman Trumbull to “abolitionize” both the Illinois Whig and Democratic parties.[7] Lincoln flatly denied the charge and challenged Douglas to provide proof.

Lincoln then abruptly changed course and began defending his House Divided doctrine (discussed in detail later). Douglas had pointed out that each state necessarily and rightfully had different local laws and institutions and that the same should be true in regards to slavery. Popular sovereignty, Douglas asserted, would calm the debate over slavery by leaving it in the hands of the people, rather than the partisans in Congress.[8] Lincoln countered that slavery was a special case; while he agreed that variety in other institutions had been “the very cements of this Union,” slavery had always been divisive and Congress merely reflected this reality. “Have we not always had quarrels and difficulties over it [slavery]?” Lincoln asked.

Changing topics once again, Lincoln took a page from Douglas’s book. Douglas had attempted to tie Lincoln to abolitionist platforms adopted by radical Republicans in Illinois. Responding in kind, Lincoln brought up various Democratic anti-slavery platforms written at various times and places in Illinois, and even one from Vermont, Douglas’s home state. Lincoln tried to dispose of this particular accusation by asserting that Douglas was just as responsible for the anti-slavery Democratic platforms as Lincoln was for the abolitionist Republican ones.[9]

In his final major argument, Lincoln attacked Douglas’s Freeport Doctrine. The Freeport Doctrine (named for the site of the previous debate, where Douglas most famously advocated it) claimed that the Dred Scott decision did not undermine popular sovereignty because slavery could not exist without local police regulations supporting it.[10] If the majority did not support slavery, then they would not pass the necessary regulations, regardless of the Supreme Court’s decision. Lincoln attacked the doctrine on two fronts. First, he pointed out that the doctrine was empirically false; Dred Scott had been held as a slave despite the lack of local police regulations in Minnesota. Second, he accused the doctrine of being inherently hypocritical; Douglas had sworn to uphold the Constitution, and the Dred Scott decision declared that the Constitution protected slavery in the territories. How could Douglas support the Court’s decision while simultaneously arguing that the territories had a right to subvert it?[11]

Lincoln concluded his address with a revealing (and in hindsight, amusing) complaint. Douglas had proclaimed in an earlier speech at Joliet that Lincoln had been so overwhelmed after the first debate at Ottawa that he had to be carried off the platform by his disheartened supporters. While it was true that Lincoln had been carried off the platform, it was by celebratory supporters and against his will. Lincoln indignantly pointed out the bizarre falsehood, wondering if “the Judge is crazy” before yielding the stage to Douglas, saying, “…let him set my knees trembling again, if he can.”

Featured Excerpt Analysis

Lincoln began his reply in a typically understated fashion, saying that “There is very much in the principles that Judge Douglas has here enunciated that I most cordially approve…” Guelzo notes that Lincoln liked “to give ‘away 6 points’ in a case, then turn and hang the case and the opposing counsel ‘on the 7th.'”[12] Following this strategy, Lincoln stressed that he entirely agreed with Douglas’s sentiment “that all States have the right to do exactly as they please about all their domestic relations, including that of slavery…”

With that said, Lincoln turned his attention to two of Douglas’s rhetorical questions. First, “Why can’t this Union endure permanently, half slave and half free?” and second, “Why can’t we let it stand as our forefathers placed it?”

On the date of his nomination for the Senate seat, Lincoln delivered his famous “House Divided” speech, the most memorable line being, “‘A house divided against itself cannot stand.’ I believe this government cannot endure permanently half slave and half free.”[13] As David Zarefsky notes, Douglas attacked the “House Divided” speech throughout the campaign, and the Jonesboro debate was no exception.[14] Douglas devoted a fair portion of his opening speech in Jonesboro to accusing Lincoln of insulting the Founders and the Constitution. “When” Douglas roared, “did he learn, and by what authority does he proclaim, that this Government is contrary to the law of God and cannot stand?…Surely, Mr. Lincoln is a wiser man than those who framed the Government.”[15]

At Jonesboro, Lincoln countered Douglas by arguing that his two questions were not actually equivalent; in Lincoln’s view, it was Douglas, not Lincoln, who had deviated from the Founders’ original thoughts on slavery. The Founders, Lincoln explained, prohibited slavery in the territories, and he merely wanted to reimpose those limits. Furthermore, Lincoln argued that the Founders had thought slavery was on the path to extinction, and wrote the Constitution accordingly. It was Lincoln and the Republicans, not Douglas, who wanted the country to stand as their forefathers placed it. Lincoln and Douglas represent two sides of a debate still being argued today; does the original version of the Constitution (and by extension, the Founders themselves) support slavery, or merely tolerate it as an existing evil? Throughout his political career Lincoln firmly maintained that the Constitution merely tolerated slavery and the Founders had assumed and intended that slavery would ultimately become extinct.[16]

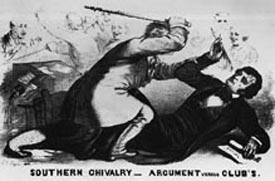

Lincoln goes on to support his argument by quoting the vehemently pro-slavery Representative Preston Brooks, who, Lincoln is happy to remind his audience, famously caned abolitionist Senator Charles Sumner on the floor of the Senate two years earlier[17], receiving “dinners, and silver pitchers, and gold-plated canes…for the feat.” Brooks himself, Lincoln noted, agreed with Lincoln’s view of the Founders, observing “when this Government was originally established, nobody expected that the institution of slavery would last until this day.” Lincoln goes on to sardonically remark that some Southern Democrats would admit this, but a Northern Democrat never would.

Lincoln’s “House Divided” doctrine was a key point in the Lincoln-Douglas debates. It may surprise modern readers that the speech was seen as a liability for Lincoln. According to Zarefsky, the speech, though often praised as visionary today, was seen as ominous and war-mongering by Lincoln’s contemporaries. Douglas not only criticized it as contrary to the Founders views, but also blurred the lines between prediction and desire, depicting Lincoln as a radical waging war on slaveholders.[18]

However, Lincoln maintained his position, and in the process, revealed the fundamental difference between himself and Douglas. Douglas viewed the debate over slavery in the territories as having three sides; pro-slavery in the form of Southern Democrats, anti-slavery Republicans, and popular sovereignty. Having been heavily influenced by Andrew Jackson, Douglas was committed to the idea of popular sovereignty, consistently promoting it as the best way to deal with the question of slavery in the territories.[19] Even in the face of strident opposition from his own party and president, Douglas continued to support the right of territories to decide their own laws.[20]

This arrangement set Douglas up as the reasonable middle-ground between two unbending factions. Lincoln deconstructed this idea. In his “House Divided” speech, Lincoln said the Union can’t stay permanently half-slave and half-free; it must become all one or the other. Therefore, there is no middle ground; if you are not opposed to the spread of slavery, then you are for it. Douglas attempted to combat this characterization by relying on the Founders for support; America’s revered forefathers had set the country up as half-slave and half-free and the country could endure half-slave and half-free. But Lincoln says the half and half nature of the country was necessity, not choice. Therefore, Lincoln argues, Douglas’s attempt to portray himself as a reasonable compromise between the two sides using the Founders as support was an illusion; in fact, Founders agreed with Lincoln, not Douglas. Secondly and most importantly, Douglas’s policy would lead to the spread of slavery as surely as Brooks’ or any other Southern Democrat’s policy; the difference, Lincoln caustically pointed out, is that Brooks was honest about it.

Lincoln’s argument as stated at Jonesboro (referred to as the historical argument by Zarefsky) was only one part of his argument with Douglas regarding the House Divided doctrine. The historical argument lent the Founders’ support to the concept, but the full import of the doctrine would become clear in later debates. Lincoln placed Douglas in the same boat as more vocal supporters of slavery by contending that, in practice, there was no significant distinction between Douglas’s doctrine of popular sovereignty and the Southern Democrats’ pro-slavery doctrine. Douglas’s neutrality in regards to slavery was the same as support due to the moral significance of the issue.

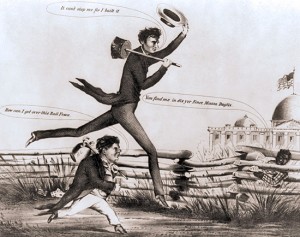

1860 Lincoln-Douglas cartoon. Despite being two years later, it still captures the public perception of the two candidates. Courtesy of House Divided.

Lincoln concluded the debates in Alton with that very point; “[Douglas] contends that whatever community wants slaves has a right to have them. So they have, if it is not a wrong. But if it is a wrong, he cannot say people have a right to do wrong.”[21]

While Douglas could directly contradict Lincoln concerning the Founders’ opinions on slavery with some justification, he had very little answer for Lincoln’s overarching moral argument. Douglas refused to argue that slavery was either a moral good or even neutral, primarily because he did not view slavery as moral issue. The closest he came to directly addressing Lincoln’s moral argument was the sixth debate at Quincy, where he said, “I do not discuss the morals of the people of Missouri, but let them settle that matter for themselves… they bear consciences as well as we, and… are accountable to God and their posterity, and not to us.”[22] Zarefsky likens their debate to the modern debate over abortion. Pro-life supporters have moral objections to abortion, as Lincoln had moral objections to slavery, while many pro-choice supporters, like Douglas, claim it is not a moral issue at all or that it is not their place to make moral judgments on the behalf of others. The two arguments exist “on different planes altogether. Neither participant can imagine the other’s categories as relevant to the matter ultimately at hand.”[23] It was the moral argument and the fundamental disconnect it created that made Lincoln and Douglas, and by extension, the nation, incapable of avoiding the coming conflict.

[1]New York Times, “Senator Douglas at Chicago,” July 13, 1858, House Divided, Dickinson College, transcribed May 15, 2008, http://hd.housedivided.dickinson.edu/node/16382

[2]”Online Essay.” House Divided, Lincoln-Douglas Debates Digital Classroom. Accessed March 16, 2015. http://housedivided.dickinson.edu/debates/essay.html

[3]George H. Mayer, The Republican Party, 1854-1964 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1964), quoted in David Zarefsky, Lincoln, Douglas, and Slavery: In the Crucible of Debate (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1990), 51.

[4]Richard Brookhiser, Founder’s Son: A Life of Abraham Lincoln (2014; Basic Books, 2014), chap. 8, http://site.ebrary.com/lib/dickinson/reader.action?docID=10956815

[5]Stephen Douglas, “Stephen Douglas to Abraham Lincoln, July 30, 1858,” House Divided, Dickinson College, adapted March 3, 2009, http://hd.housedivided.dickinson.edu/node/25347

[6]Allen C. Guelzo, Lincoln and Douglas: The Debates that Defined America (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2008), 172-173.

[7]Ibid., 173.

[8]Ibid., 175.

[9]Michael Burlingame, Abraham Lincoln: A Life (2008: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008), chap. 13, http://www.knox.edu/about-knox/lincoln-studies-center/burlingame-abraham-lincoln-a-life

[10]Among other things, the Supreme Court’s ruling in the Dred Scott case said that any law barring slavery in the territories was in violation of the Fifth Amendment, seemingly making Douglas’s simultaneous support of popular sovereignty and support of the Court’s decision contradictory.

[11]Burlingame, Abraham Lincoln: A Life, chap. 13.

[12]Guelzo, Lincoln and Douglas, 151.

[13]Abraham Lincoln, “A House Divided,” House Divided, Dickinson College, adapted May 30, 2013, http://hd.housedivided.dickinson.edu/node/40361

[14]Zarefsky, Lincoln, Douglas, and Slavery, 142.

[15]Stephen Douglas, “Third Joint Debate at Jonesboro, Mr. Douglas’s Speech,” Bartleby.com, accessed March 17, 2015, http://www.bartleby.com/251/31.html

[16]Brookhiser, Founder’s Son, chap. 8.

[17]”The Caning of Senator Charles Sumner,” The United States Senate, accessed March 19, 2015, https://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/history/minute/The_Caning_of_Senator_Charles_Sumner.htm

[18]Zarefsky, Lincoln, Douglas, and Slavery, 141-142.

[19]Eric T. Dean Jr., “Stephen A. Douglas and Popular Sovereignty,” Historian 57, no. 4 (1995): 739-740, https://envoy.dickinson.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=hlh&AN=9508234209&site=eds-live

[20]Douglas split with Buchanan and Southern Democrats over Kansas’ admission to the Union under Lecompton constitution. Pro-slavery Kansans gathered in Lecompton, Kansas to write the state constitution. Suspecting fraud, Free-Soilers boycotted the convention and refused to have anything to do with the product. While many Democrats, including Buchanan, strongly advocated for Kansas to be admitted as a slave state under the Lecompton constitution, Douglas openly defied them, arguing that the document was not the result of popular sovereignty and should be discarded. See http://hd.housedivided.dickinson.edu/node/9601 and Burlingame, Abraham Lincoln: A Life, chap. 12.

[21]Abraham Lincoln, “Last Joint Debate at Alton, Mr. Lincoln’s Reply,” Bartleby.com, accessed March 18, 2015, http://www.bartleby.com/251/1001.html

[22]Stephen Douglas, “Sixth Joint Debate at Quincy, Mr. Douglas’s Reply,” Bartleby.com, accessed April 8, 2015, http://www.bartleby.com/251/62.html

[23]Zarefsky, Lincoln, Douglas, and Slavery, 195.

Bibliography

Brookhiser, Richard. Founder’s Son: A Life of Abraham Lincoln. 2014. Basic Books, 2014. ProQuest ebrary. http://site.ebrary.com/lib/dickinson/reader.action?docID=10956815

Burlingame, Michael. Abraham Lincoln: A Life. 2008. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008. http://www.knox.edu/about-knox/lincoln-studies-center/burlingame-abraham-lincoln-a-life.

“The Caning of Senator Charles Sumner.” The United States Senate. Accessed March 19, 2015. https://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/history/minute/The_Caning_of_Senator_Charles_Sumner.htm.

Dean Jr., Eric T. “Stephen A. Douglas and Popular Sovereignty.” Historian 57, no. 2 (1995): 733-748. https://envoy.dickinson.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=hlh&AN=9508234209&site=eds-live

Douglas, Stephen. “Stephen Douglas to Abraham Lincoln, July 30, 1858.” House Divided. Dickinson College. Adapted March 3, 2009. http://hd.housedivided.dickinson.edu/node/25347.

Douglas, Stephen. “Third Joint Debate at Jonesboro, Mr. Douglas’s Speech.” Bartleby.com. Accessed March 17, 2015. http://www.bartleby.com/251/31.html.

Douglas, Stephen. “Sixth Joint Debate at Quincy, Mr. Douglas’s Reply.” Bartleby.com. Accessed April 8, 2015. http://www.bartleby.com/251/62.html

Guelzo, Allen. Lincoln and Douglas: The Debates that Defined America. New York: Simon and Schuster, 2008.

Huston, James L. “Democracy by Scripture versus Democracy by Process: A Reflection on Stephen A. Douglas and Popular Sovereignty.” Civil War History 43, no. 3 (1997): 189-200. http://eds.a.ebscohost.com/eds/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?sid=b86ad2be-b0fd-4ea9-92ac-2ff9c00887e9%40sessionmgr4002&vid=6&hid=4211

Lincoln, Abraham. “A House Divided.” House Divided. Dickinson College. Adapted May 30, 2013. http://hd.housedivided.dickinson.edu/node/40361.

Lincoln, Abraham. “Last Joint Debate at Alton, Mr. Lincoln’s Reply.” Bartleby.com. Accessed March 18, 2015. http://www.bartleby.com/251/1001.html

Mayer, George H. The Republican Party, 1854-1964. New York: Oxford University Press, 1964. Quoted in David Zarefsky, Lincoln, Douglas, and Slavery: In the Crucible of Public Debate (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 1990), 51.

New York Times. “Stephen Douglas at Chicago.” July 13, 1858. House Divided. Dickinson College. Transcribed May 15, 2008. http://hd.housedivided.dickinson.edu/node/16382.

“Online Essay.” House Divided, Lincoln-Douglas Debates Digital Classroom. Accessed March 16, 2015. http://housedivided.dickinson.edu/debates/essay.html.

Woods, Michael E. Review of Stephen A. Douglas and Antebellum Democracy by Martin H. Quitt and The Failure of Popular Sovereignty: Slavery, Manifest Destiny, and the Radicalization of Southern Politics by Christopher Childers. Civil War History 60, no. 2 (2014): 205-208. http://eds.a.ebscohost.com/eds/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?sid=b86ad2be-b0fd-4ea9-92ac-2ff9c00887e9%40sessionmgr4002&vid=4&hid=4211

Zarefsky, David. Lincoln, Douglas, and Slavery: In the Crucible of Public Debate. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1990.

Leave a Reply