Looking into the phrase “Underground Railroad” also suggests two essential questions: who coined the metaphor? And why would they want to compare and inextricably link a wide-ranging effort to support runaway slaves with an organized network of secret railroads?

The answers can be found in the abolitionist movement. Abolitionists, or those who agitated for the immediate destruction of slavery, wanted to publicize, and perhaps even exaggerate, the number of slave escapes and the extent of the network that existed to support those fugitives. According to the pioneering work of historian Larry Gara, abolitionist newspapers and orators were the ones who first used the term “Underground Railroad” during the early 1840s, and they did so to taunt slaveholders.[1] To some participants this seemed a dangerous game. Frederick Douglass, for instance, claimed to be appalled. “I have never approved of the very public manner in which some of our western friends have conducted what they call the underground railroad,” he wrote in his Narrative in 1845, warning that “by their open declarations” these mostly Ohio-based (“western”) abolitionists were creating an “upperground railroad.”[2]

Publicity about escapes and open defiance of federal law only spread in the years that followed, especially after the controversial Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. Anxious fugitives and their allies now fought back with greater ferocity. Douglass himself became more militant. In September 1851, he helped a former slave named William Parker escape to Canada after Parker had spearheaded a resistance in Christiana, Pennsylvania, that left a Maryland slaveholder dead and federal authorities in disarray. The next year in a fiery speech at Pittsburgh, the famous orator stepped up the rhetorical attack, vowing, “The only way to make the Fugitive Slave Law a dead letter is to make half a dozen or more dead kidnappers”.[3] This level of defiance was not uncommon in the anti-slavery North and soon imperiled both federal statute and national union. Between 1850 and 1861, there were only about 350 fugitive slave cases prosecuted under the notoriously tough law, and none in the abolitionist-friendly New England states after 1854.[4] White southerners complained bitterly while abolitionists grew more emboldened.

Students often seem to imagine runaway slaves cowering in the shadows while ingenious “conductors” and “stationmasters” devised elaborate secret hiding places and coded messages to help spirit fugitives to freedom. They make few distinctions between North and South, often imagining that slave patrollers and their barking dogs chased terrified runaways from Mississippi to Maine. Instead, the Underground Railroad deserves to be explained in terms of sectional differences and the coming of the Civil War.

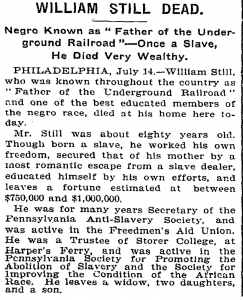

One way to grasp the Underground Railroad in its full political complexity is to look closely at the rise of abolitionism and the spread of free black vigilance committees during the 1830s. Nineteenth-century American communities employed extra-legal “vigilance” groups whenever they felt threatened. During the mid-1830s, free black residents first in New York and then across other northern cities began organizing vigilant associations to help them guard against kidnappers. Almost immediately, however, these groups extended their protective services to runaway slaves. They also soon allied themselves with the new abolitionist organizations, such as William Lloyd Garrison’s Anti-Slavery Society. The most active vigilance committees were in Boston, Detroit, New York, and Philadelphia led by now largely forgotten figures such as Lewis Hayden, George DeBaptiste, David Ruggles, and William Still.[5] Black men typically dominated these groups, but membership also included whites, such as some surprisingly feisty Quakers and at least a few women. These vigilance groups constituted the organized core of what soon became known as the Underground Railroad. Smaller communities organized too, but did not necessarily invoke the “vigilance” label, nor integrate as easily across racial, religious, and gender lines. Nonetheless, during the 1840s when William Parker formed a “mutual protection” society in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, or when John Brown created his League of Gileadites in Springfield, Massachusetts, they emulated this vigilance model.

These committees functioned more or less like committees anywhere—electing officers, holding meetings, keeping records, and raising funds. They guarded their secrets, but these were not covert operatives in the manner of the French Resistance. In New York, the vigilance committee published an annual report. Detroit vigilance agents filled newspaper columns with reports about their monthly traffic. Several committees released the addresses of their officers. One enterprising figure circulated a business card that read, “Underground Railroad Agent”.[6] Even sensitive material often got recorded somewhere. A surprising amount of this secret evidence is also available for classroom use. One can explore letters detailing Harriet Tubman’s comings and goings, and even a reimbursement request for her worn-out shoes, by using William Still’s The Underground Railroad (1872), available online in a dozen different places, and which presents the fascinating materials he collected as head of the Philadelphia Vigilance Committee. Anyone curious about how much it cost to help runaways can access the site where social studies teacher Dean Eastman and his students at Beverly High School have transcribed and posted the account books of the Boston vigilance committee. And the list of accessible Underground Railroad material grows steadily.

But how did these northern vigilance groups get away with such impudence? How could they publicize their existence and risk imprisonment by keeping records that detailed illegal activities? The answer helps move the story into the 1840s and 1850s and offers a fresh way for teachers to explore the legal and political history of the sectional crisis with students. Those aiding fugitives often benefited from the protection of state personal liberty laws and from a general reluctance across the North to encourage federal intervention or reward southern power. In other words, it was all about states’ rights—northern states’ rights. As early as the 1820s, northern states led by Pennsylvania had been experimenting with personal liberty or anti-kidnapping statutes designed to protect free black residents from kidnapping, but which also had the effect of frustrating enforcement of federal fugitive slave laws (1793 and 1850). In two landmark cases—Prigg v. Pennsylvania (1842) and Ableman v. Booth (1859)—the Supreme Court threw out these northern personal liberty protections as unconstitutional.

Students accustomed to equating states’ rights with South Carolina may be stunned to learn that it was the Wisconsin supreme court asserting the nullification doctrine in the mid-1850s. They may also be shocked to discover that a federal jury in Philadelphia had acquitted the lead defendant in the Christiana treason trial within about fifteen minutes. These northern legislatures and juries were, for the most part, indifferent to black civil rights, but they were quite adamant about asserting their own states’ rights during the years before the Civil War. This was the popular sentiment exploited by northern vigilance committees that helped sustain their controversial work on behalf of fugitives.

That is also why practically none of the Underground Railroad agents in the North experienced arrest, conviction, or physical violence. No prominent Underground Railroad operative ever got killed or spent significant time in jail for helping fugitives once they crossed the Mason-Dixon Line or the Ohio River. Instead, it was agents operating across the South who endured the notorious late-night arrests, long jail sentences, torture, and sometimes even lynching that made the underground work so dangerous. In 1844, for example, a federal marshal in Florida ordered the branding of Jonathan Walker, a sea captain who had been convicted of smuggling runaways, with the mark “S.S.” (“slave-stealer”) on his hand. That kind of barbaric punishment simply did not happen in the North.

What did happen, however, was growing rhetorical violence. The war of words spread. Threats escalated. Metaphors hardened. The results then shaped the responses the led to war. By reading and analyzing the various Southern secession documents from the winter of 1860–1861, one will find that nearly all invoke the crisis over fugitives.[7] The battle over fugitives and those who aided them was a primary instigator for the national conflict over slavery. Years afterward, Frederick Douglass dismissed the impact of the Underground Railroad in terms of the larger fight against slavery, comparing it to “an attempt to bail out the ocean with a teaspoon”.[8] But Douglass had always been cool to the public value of the metaphor. Measured in words, however—through the antebellum newspaper articles, sermons, speeches, and resolutions generated by the crisis over fugitives—the “Underground Railroad” proved to be quite literally a metaphor that helped launch the Civil War.

[1] Larry Gara, The Liberty Line: The Legend of the Underground Railroad (1961; Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1996), 143–144.

[2] Frederick Douglass, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass: An American Slave (Boston: Anti-Slavery Office, 1845), 101 (http://www.docsouth.unc.edu/neh/douglass/douglass.html).

[3] Frederick Douglass, “The Fugitive Slave Law: Speech to the National Free Soil Convention in Pittsburgh,” August 11, 1852 (http://www.lib.rochester.edu/index.cfm?PAGE=4385).

[4] See the appendix in Stanley W. Campbell, The Slave Catchers: Enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Law: 1850–1860 (New York: W. W. Norton, 1970), 199–207.

[5] Out of these four notable black leaders, only David Ruggles has an adult biography available in print. See Graham Russell Gao Hodges, David Ruggles: A Radical Black Abolitionist and the Underground Railroad in New York City (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010).

[6] Jermain Loguen of Syracuse, New York. See Fergus M. Bordewich, Bound for Canaan: The Underground Railroad and the War for the Soul of America (New York: HarperCollins, 2005), 410.

[7] See secession documents online at The Avalon Project from Yale Law School (http://avalon.law.yale.edu/subject_menus/csapage.asp).

[8] Frederick Douglass, Life and Times of Frederick Douglass (Hartford, CT: Park Publishing, 1881), 272 (http://docsouth.unc.edu/neh/douglasslife/douglass.html).

This essay was reposted from History Now (Winter 2010), an online magazine of the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History.

![1865-04-14 Garrison [?] at Sumter](http://blogs.dickinson.edu/hist-288pinsker/files/2015/03/1865-04-14-Garrison-at-Sumter-163x300.png)

![Image 3 Garrison [?] standing center](http://blogs.dickinson.edu/hist-288pinsker/files/2015/03/Image-3-Garrison-standing-center-1024x638.png)

Even to begin a lesson by examining the two words “underground” and “railroad” helps provide a tighter chronological framework than usual with this topic. There could be no “underground railroad” until actual railroads became familiar to the American public–in other words, during the 1830s and 1840s. There had certainly been slave escapes before that period, but they were not described by any kind of railroad moniker. The phrase also highlights a specific geographic orientation. Antebellum railroads existed primarily in the North–home to about 70 percent of the nation’s 30,000 miles of track by 1860. Slaves fled in every direction of the compass, but the metaphor packed its greatest wallop in those communities closest to the nation’s whistle-stops.

Even to begin a lesson by examining the two words “underground” and “railroad” helps provide a tighter chronological framework than usual with this topic. There could be no “underground railroad” until actual railroads became familiar to the American public–in other words, during the 1830s and 1840s. There had certainly been slave escapes before that period, but they were not described by any kind of railroad moniker. The phrase also highlights a specific geographic orientation. Antebellum railroads existed primarily in the North–home to about 70 percent of the nation’s 30,000 miles of track by 1860. Slaves fled in every direction of the compass, but the metaphor packed its greatest wallop in those communities closest to the nation’s whistle-stops.

precarious freedom also applied indirectly to runaways who had nothing to do with the war effort. The War Department had begun issuing orders to field commanders as early as

precarious freedom also applied indirectly to runaways who had nothing to do with the war effort. The War Department had begun issuing orders to field commanders as early as

field makes it obvious that this must have been the eldest child of widow Barbara

field makes it obvious that this must have been the eldest child of widow Barbara

For more on George J. Dinkel (or Dinkle)’s service in the 114th Illinois Infantry, see

For more on George J. Dinkel (or Dinkle)’s service in the 114th Illinois Infantry, see

A quick check of the 1900 census confirms that 75-year-old Barbara Dinkel (mother) was living in Barry County, Michigan with her 53-year-old son George (b. Dec. 1846 in Illinois), his much younger second wife Emily (born in Michigan) and their three small children. According to the census, George J. Dinkel was then a dry goods merchant in town. There is also a death record from 1909 for a “George S. Dinkel” from Barry, Michigan transcribed in Ancestry that lists his birth year as 1846 and his father as Philip Dinkel. He is buried in nearby Riverside Cemetery in Kalama

A quick check of the 1900 census confirms that 75-year-old Barbara Dinkel (mother) was living in Barry County, Michigan with her 53-year-old son George (b. Dec. 1846 in Illinois), his much younger second wife Emily (born in Michigan) and their three small children. According to the census, George J. Dinkel was then a dry goods merchant in town. There is also a death record from 1909 for a “George S. Dinkel” from Barry, Michigan transcribed in Ancestry that lists his birth year as 1846 and his father as Philip Dinkel. He is buried in nearby Riverside Cemetery in Kalama