April 1861

“In June 1861, delegates to a convention in the Unionist stronghold of Wheeling elected Francis H. Pierpont governor of this new ‘state,’ and in July the Wheeling convention elected two prominent Unionists Waitman T. Willey and John S. Carlile, to represent the loyalists of western Virginia in the U.S. Senate. For these Unionists, defiance of the Confederacy was an extension of a decades-old battle against the slaveholding elite of eastern Virginia…” (Varon, Armies of Deliverance, Chapter 1)

Willey’s son was a student at Dickinson College (Class of 1862). He wrote some anxious letters home in April at the outbreak of the war. He seemed unsure as to how his own father felt about secession.

| William Willey to Waitman Willey, April 22, 1861 | |

| William Willey to Waitman Willey, April 29, 1861 |

Green Together –First Bull Run

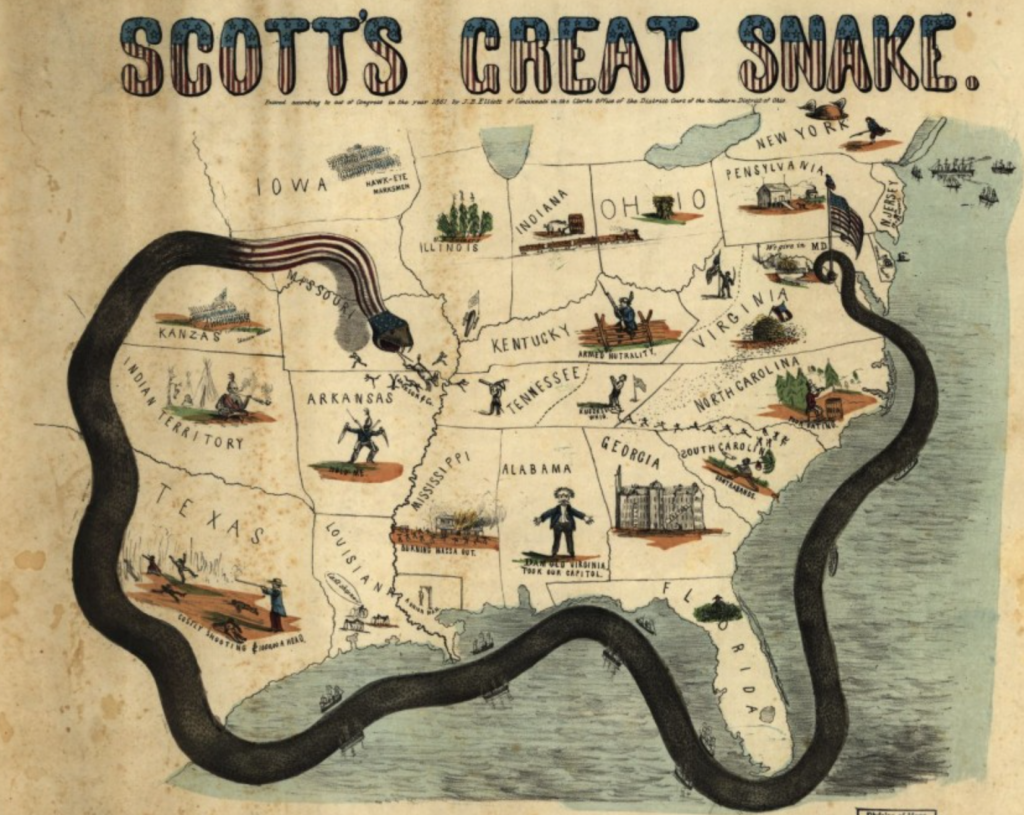

Winfield Scott served as general in chief of the Union armies at the outset of the Civil War at the age of 74. He was a Virginian by birth and a Constitutional Unionist by choice. During the Sumter crisis in March and April 1861, he clashed with President Lincoln over strategy. Once the war began, Scott outlined a deliberate strategy for the Union forces which newspaper’s nicknamed “The Anaconda Plan.” After months of tension, Scott finally retired from active duty in November 1861 replaced by 34-year-old Gen. George McClellan, a well-trained officer with Democratic leanings who largely tried to follow Scott’s original plan despite pressure from both the Republican president and the Republican-controlled Congress.

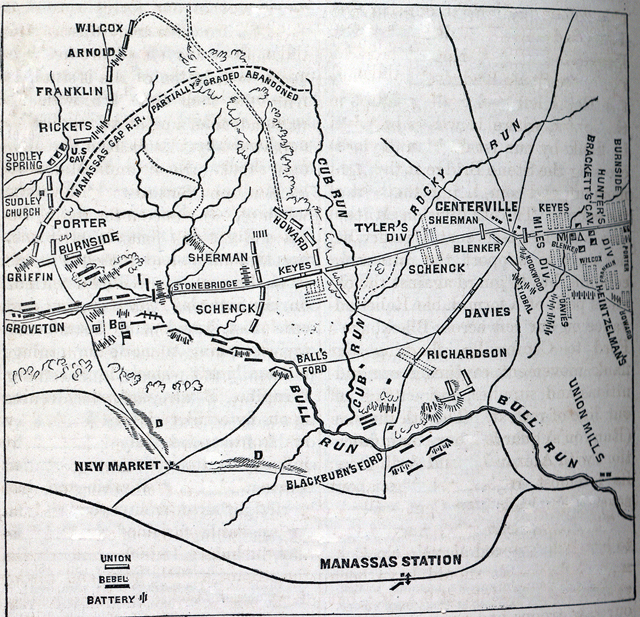

First Major Battle –Bull Run (July 1861)

The Battle of Bull Run or Manassas on July 21, 1861 was a small engagement by later Civil War standards, but it was a pivotal confrontation that illustrated almost all of the challenges each side faced in mobilizing for war. Students in History 288 should be able to identify at least two or three major elements of the episode that demonstrate important trends in the war’s first year.

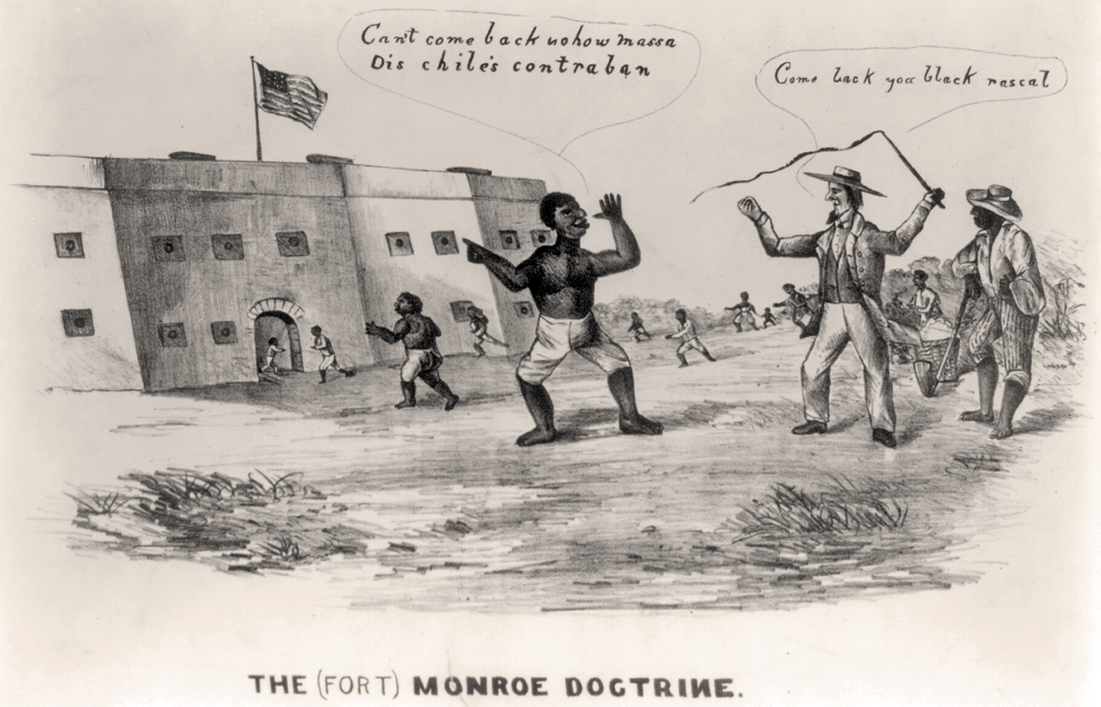

Contraband Policy

Adam Goodheart has an excellent piece adapted from his book 1861 and available online from the New York Times magazine that details the story of three Virginia slaves –Frank Baker, Shepard Mallory and James Townsend– who rowed across the James River on May 23, 1861 and presented themselves to Union army officials at Fort Monroe near Norfolk, setting in motion a chain of events that led General Benjamin Butler to get approval from the War Department effectively declaring these men as “contraband of war” and preventing them from being returned to their Confederate army masters. You can read Butler’s first dispatch on the subject (May 24, 1861) and the encouraging response from the War Department (May 30, 1861), which tentatively authorized the contraband policy. See also a more complete authorization from Secretary of War Simon Cameron on August 8, 1861.

Missouri, Kentucky and the West

When Fremont balked, Lincoln removed him from command.” –Varon, chapter 1

- John Fremont

- Jesse Benton Fremont

Wilson’s Creek (August 10, 1861) was the first major battle in the West and like Bull Run was a devastating defeat for Union forces, including the first death of a general: Nathaniel Lyon. On August 30, 1861, Union general John Fremont issued a martial law declaration for Missouri that also included a general emancipation of rebel slaves. In an exchange of private letters, President Lincoln pushed Fremont to modify his order. “When Fremont balked,” writes historian Elizabeth Varon, “Lincoln relieved him from command” (p. 42).

Fremont had actually sent his wife, Jesse Benton Fremont, an experienced politico herself, to deliver his response to the White House. She did so apparently around midnight on September 10, 1861. There was some kind of dramatic confrontation between Mrs. Fremont and President Lincoln that evening at the White House although its nature has been disputed. Two years later, the president recalled, according to the wartime diary of a close aide, that she “taxed me violently” during their conversation, although much of their argument by his recollection concerned rumors of Fremont’s administrative incompetence and factional politics in Missouri and not either martial law or emancipation (John Hay diary, December 9, 1863). This claim of the president’s is supported by a private memo from another White House aide (John Nicolay) produced just a week after the confrontation which asserted that the “matter of the Proclamation … did not enter into the trouble with the Gen” (September 17, 1861). Years later, Jesse Fremont remembered it much differently, claiming in 1891 that Lincoln was focused almost solely on the dangers of emancipation and had told her: “the General should never have dragged the Negro into the war.” This is not a very credible recollection, but it has appeared in various forms in many secondary sources and presumably helped inform Varon’s outlook.

Moncure Conway

The war vaulted [Moncure] Conway to prominence. In his popular lectures in the North and in his antislavery treatises The Rejected Stone (1861) and The Golden Hour (1862), Conway defended Fremont as the ‘Warrior of Liberty’ and denounced his removal. He implored Lincoln to enact immediate abolition under his constitutional war powers and argued that slavery, not the South was the Union’s true enemy. –Varon, Armies of Deliverance, Chapter 1