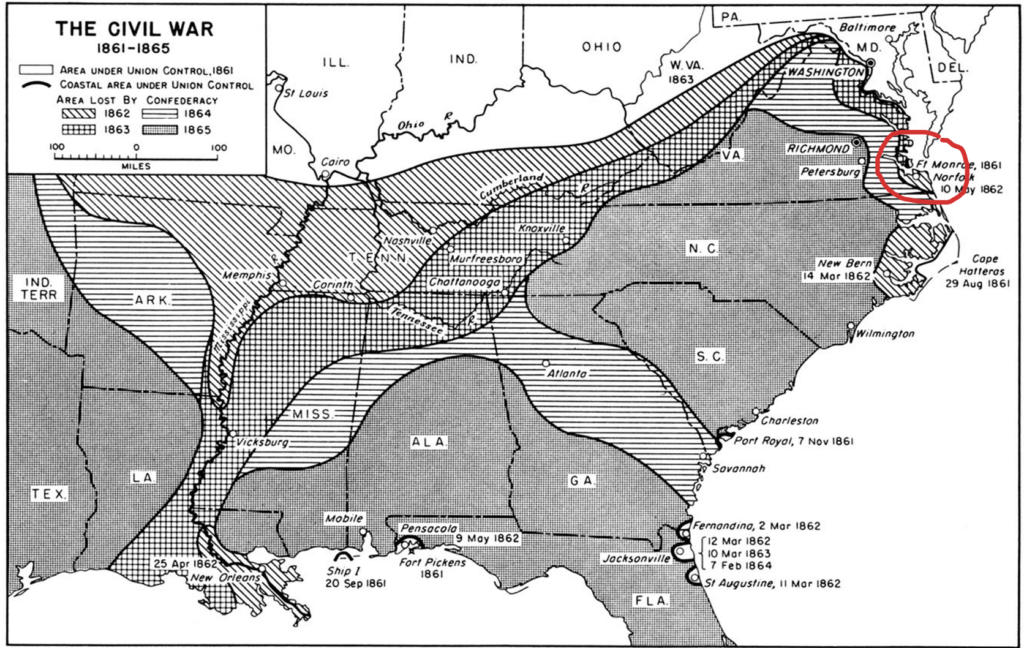

Peninsula Campaign (March – July, 1862)

Second Confiscation Act (July 1862)

“Went to Cabinet at the appointed hour. It was unanimously agreed that the Order in respect to Colonization should be dropped; and the others were adopted unanimously, except that I wished North Carolina included among the States named in the first order. The question of arming slaves was then brought up and I advocated it warmly. The President was unwilling to adopt this measure, but proposed to issue a Proclamation, on the basis of the Confiscation Bill, calling upon the States to return to their allegiance — warning the rebels the provisions of the Act would have full force at the expiration of sixty days — adding, on his own part, a declaration of his intention to renew, at the next session of Congress, his recommendation of compensation to States adopting the gradual abolishment of slavery — and proclaiming the emancipation of all slaves within States remaining in insurrection on the first of January, 1863.”–Diary of Salmon P. Chase, Secretary of Treasury, Tuesday, July 22, 1862Greeley & Lincoln

Varon on the interpretative arguments

“Seen in this light, Lincoln’s August meeting with the black delegates and his letter to Greeley were command performances, each with its own distinct purposes…Together, the two performances were evidence of Lincoln’s political genius: he would free the slaves by presidential edict only after having demonstrated to the public that he had in good faith tried the other options, and that colonization and gradual, voluntary emancipation had fallen short as measures for weakening the Confederacy. Dissenting voices among modern historians reject the ‘political genius’ interpretation. They argue that Lincoln persistently lagged behind the antislavery vanguard of abolitionists and Radical Republicans –he was not ready to consider the prospect of black citizenship and equal rights– and that we should take him at his word when he professed to put reunion above all other considerations and to favor colonization as the destiny for freed slaves.” –Varon, Armies, pp. 114-15

Close Reading: Lincoln to Greeley (August 22, 1862)

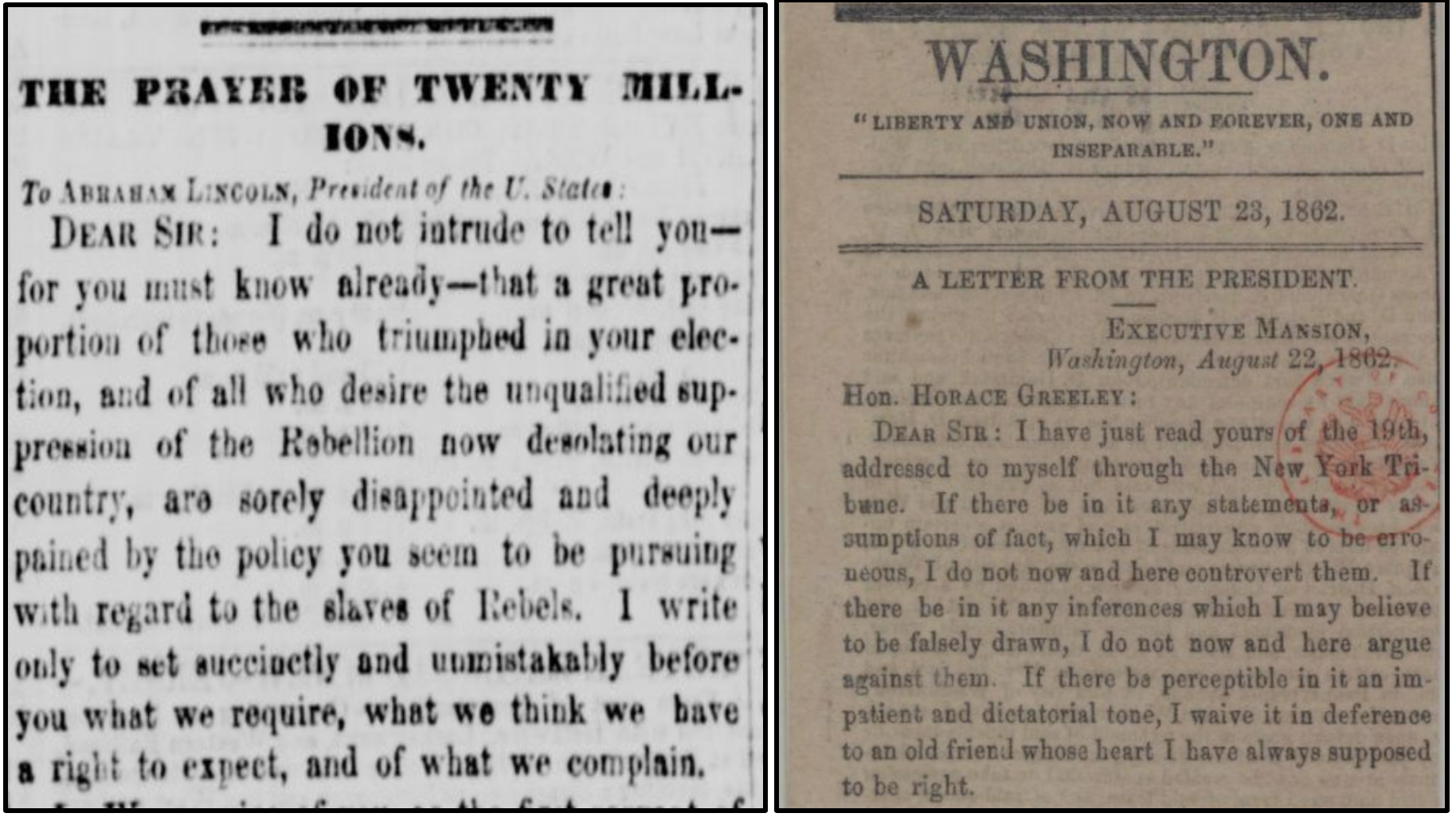

On August 20, 1862, Horace Greeley, editor of the New York Tribune, published a scathing open letter to Abraham Lincoln, entitled, “The Prayer of Twenty Millions.” Here is an excerpt:

I do not intrude to tell you–for you must know already–that a great proportion of those who triumphed in your election, and of all who desire the unqualified suppression of the Rebellion now desolating our country, are sorely disappointed and deeply pained by the policy you seem to be pursuing with regard to the slaves of the Rebels. I write only to set succinctly and unmistakably before you what we require, what we think we have a right to expect, and of what we complain. We think you are strangely and disastrously remiss in the discharge of your official and imperative duty with regard to the emancipating provisions of the new Confiscation Act….Why these traitors should be treated with tenderness by you, to the prejudice of the dearest rights of loyal men, We cannot conceive.

Lincoln’s response, dated August 22, 1862, appeared in the Washington Daily National Intelligencer on the following day. The transcript below (with spelling errors and corrections) derives from his handwritten original.

Executive Mansion,

Washington, August 22, 1862.

Hon. Horace Greely:

Dear Sir–

Horace Greeley (1811-1872)

I have just read yours of the 19th. addressed to myself through the New-York Tribune. If there be in it any statements, or assumptions of fact, which I may know to be erroneous, I do not, now and here, controvert them. If there be in it any inferences which I may believe to be falsely drawn, I do not now and here, argue against them. If there be perceptable in it an impatient and dictatorial tone, I waive it in deference to an old friend, whose heart I have always supposed to be right. As to the policy I “seem to be pursuing” as you say, I have not meant to leave any one in doubt.

I would save the Union. I would save it the shortest way under the Constitution. The sooner the national authority can be restored; the nearer the Union will be “the Union as it was.” Broken eggs can never be mended, and the longer the breaking proceeds the more will be broken. If there be any those who would not save the Union, unless they could at the same time save slavery, I do not agree with them. If there be any those who would not save the Union unless they could at the same time destroy slavery, I do not agree with them. My paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union, and is not either to save or to destroy slavery [emphasis added]. If I could save the Union without freeing any slave I would do it, and if I could save it by freeing all the slaves I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing some and leaving others alone I would also do that. What I do about slavery, and the colored race, I do because I believe it helps to save the Union; and what I forbear, I forbear because I do not believe it would help to save the Union. I shall do less whenever I shall believe what I am doing hurts the cause, and I shall do more whenever I shall believe doing more will help the cause. I shall try to correct errors when shown to be errors; and I shall adopt new views so fast as they shall appear to be true views.

I have here stated my purpose according to my view of official duty; and I intend no modification of my oft-expressed personal wish that all men every where could be free.

Yours, A. LINCOLN

Dueling public letters between the New York Tribune’s Horace Greeley (left) and President Lincoln via the Washington National Intelligencer (right)