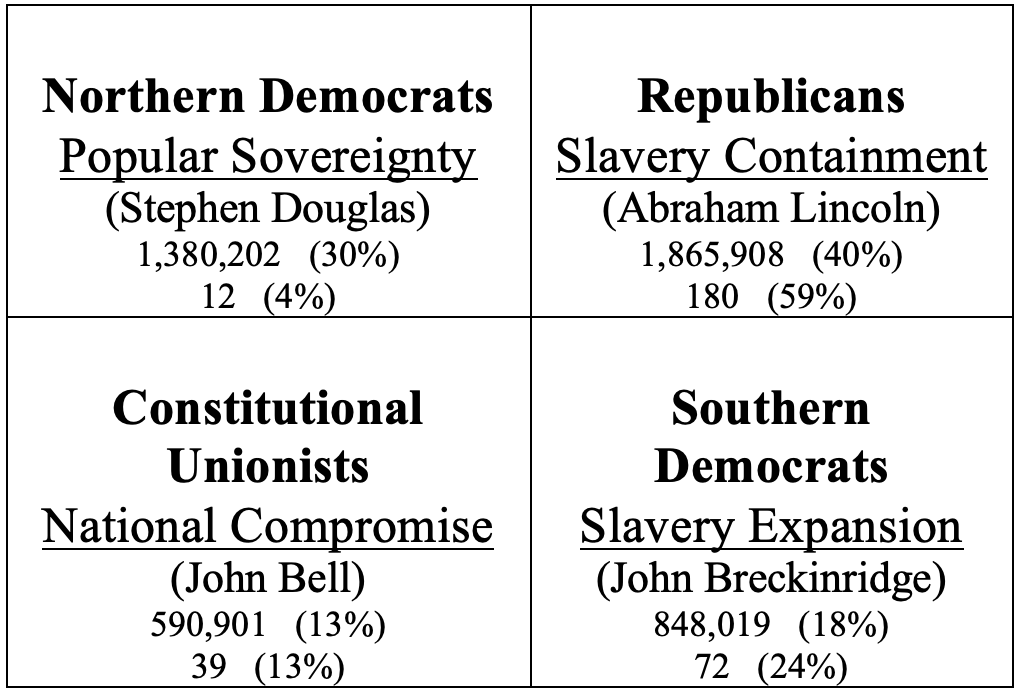

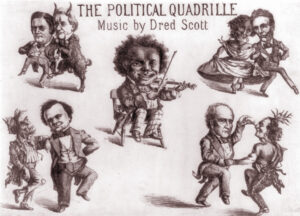

The election of 1860 was unique in American history because it was the only contest (so far) where one of the losing parties refused to accept the results as legitimate. There were actually four political parties vying for the 1860 victory. Students in History 288 should be able to identify all four factions. One way to do so would be to interpret the political cartoon on the right. Who are the four candidates dancing to Dred Scott’s “quadrille”? But students in History 288 also need to understand the issues at stake in 1860. As the cartoon indicates, the legacy of the Dred Scott Decision still loomed large over the electorate, but another cartoon from the campaign also suggests that a different event was just as salient.

The election of 1860 was unique in American history because it was the only contest (so far) where one of the losing parties refused to accept the results as legitimate. There were actually four political parties vying for the 1860 victory. Students in History 288 should be able to identify all four factions. One way to do so would be to interpret the political cartoon on the right. Who are the four candidates dancing to Dred Scott’s “quadrille”? But students in History 288 also need to understand the issues at stake in 1860. As the cartoon indicates, the legacy of the Dred Scott Decision still loomed large over the electorate, but another cartoon from the campaign also suggests that a different event was just as salient.

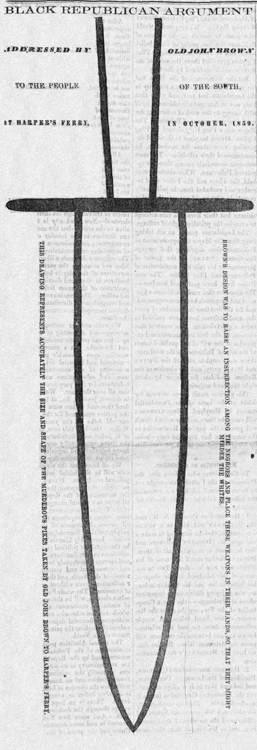

The image to the left, entitled “Black Republican Argument,” actually appeared in a Pennsylvania newspaper late in the campaign. The stark image depicts the use of John Brown’s Raid by southern Democrats. Brown was an abolitionist originally from Connecticut who had become notorious because of his actions in the Kansas Territory. Brown and his sons had been deeply involved in the battles of “Bleeding Kansas,” and he stood accused of murdering at least five pro-slavery settlers in cold blood. Brown, however, was a hero to many abolitionists and northern blacks who revered his fierce anti-slavery stance and his remarkably modern form of egalitarianism. Brown was almost a romantic revolutionary in areas of the North, because of his bold plans of action. Brown’s plans culminated at the end of the 1850s with a series of raids into southern territory, first in Missouri in 1858 and then at the federal arsenal in Harpers Ferry in what was then western Virginia (and what is now West Virginia). Brown was captured during his October 1859 raid at Harpers Ferry, put on trial by the state of Virginia and then executed in December. His execution for treason in 1859 marked an important bookend with the Christiana treason trial of 1851 and helps explain why the nation appeared closer to disunion at the end of the decade than at the beginning.

For most of the 1860 campaign, Abraham Lincoln himself was absent. Like most (but not all) presidential candidates of that era, Lincoln did not campaign openly for the office. According to his law partner, Lincoln was left feeling “bored –bored badly” by this tradition. His boredom, however, might help explain a fascinating exchange candidate Lincoln conducted with an eleven-year-old girl from New York in October 1860. Young Grace Bedell wrote Lincoln urging him to grow a beard because his face was “so thin.” Lincoln responded asking whether or not such a move might appear as an “affectation,” but within days after his November victory, Lincoln began growing the beard. Later, President-Elect Lincoln met the young girl and the two of them had an ongoing correspondence during the Civil War –although this fact was not known to scholars until very recently. The full story of the relationship is detailed here at the Blog Divided.