As I begin my next project, it is important to organize the research into a coherent structure for the best effect. My task is to document the connections between Dickinson’s founders and slavery, a subject that holds particular relevance today as many colleges and universities such as Brown, Georgetown and Harvard are examining their own ties to the institution.

First, I sought out biographical information concerning four individuals who were crucial in Dickinson’s early years—Benjamin Rush, the college’s founder, John Dickinson, its chief financier and namesake, John Montgomery, a Carlisle resident and early board member and Dr. Charles Nisbet, a Scotsman who served as Dickinson’s first president. All but Nisbet owned slaves at one point in their lives, and with the apparent exception of Montgomery, they all leveled at least some criticism towards slavery, even if their words did not appear to match their actions.

Examining their roles within the college, I found that Montgomery and Rush were particularly close. When problems arose with the new college, Rush frequently leaned upon Montgomery for assistance. A generic search of their names through the Dickinson College Archives’ JumpStart Catalog turned up a student essay from 1982, which further fleshed out the relationship between the founder and the prominent townsman. It was clear, after just some preliminary research, that the stories of Montgomery and Rush might be told best together. Both were slave owners and Dickinson founders, yet each characterized his slaveholding in a vastly different light.

To better understand both men (particularly Montgomery), I began to further explore their connections to slavery in Cumberland County. Montgomery was one of the largest Cumberland County slaveholders, and both men frequently associated with other local slave owners. I started my research in the Board of Trustees papers in the Dickinson archives (RG 1/1), where I found evidence of many slaveholding families—the Montgomerys, the Duncans, the Wilsons to name a few—serving on the board or making important contributions. For instance, in 1800, Revolutionary War veteran William Irvine (another Carlisle slaveholder) was given power of attorney by the Board. [1] The point—Dickinson’s early operating Board was heavily dominated by slaveholders. In order to explain this, I might employ a visual representation of board seats and demonstrate how many were occupied by members of slaveholding households.

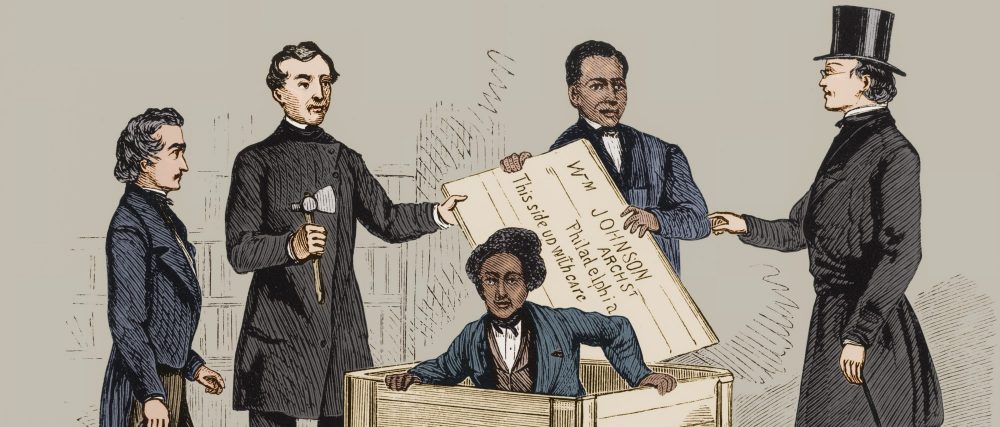

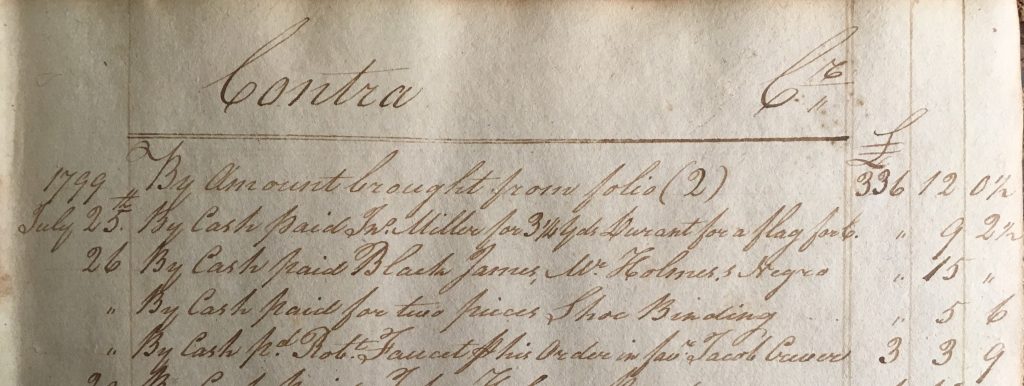

Then, Cory Young, a graduate student from Georgetown University specializing in slaveholder migration, shared his newest finding with me—evidence in Dickinson’s financial records (kept by Treasurer John Montgomery) that slave labor was used in constructing the college. On July 26, 1799, records show a single 15 shilling payment made to”Black James, Mr. Holmes’s Negro.” [2] This could be the same “Negroe Boy named Jim” who was about 10 years old when he was registered by William Holmes of Carlisle in October 1780, under the state’s Gradual Abolition Law. Nevertheless, this represents an important point of research. Young informed me that there are many other payments made by the college to local slaveholders, leaving the potential that more enslaved people were involved in building Dickinson. (He has experience in this. As a student at Georgetown, he worked on finding records of Georgetown’s use of slave labor, which included the hiring out of college-owned slaves). As all funds were approved by the Board, an important aspect of my research going forward will be to determine how widespread slave labor was in Dickinson’s construction, and if the Board consistently contracted with local slaveholders.

On July 26, 1799, “Black James,” an enslaved man, was hired out to the college by his master. Dickinson’s early financial ledgers show a 15 shilling payment for work done on the initial college building, which burned down in 1803. (Dickinson College Archives)

Turning to Charles Nisbet, I find that he and college namesake John Dickinson had a less than amiable relationship. Apparently not a fan of Nisbet, Dickinson wrote several disheartening letters to the Scotsman, attempting to put the brakes on his trans-Atlantic voyage to assume the college presidency. The delaying tactics angered Rush and Montgomery, who wondered on paper if Dickinson was seeking to sabotage the school. [3] Nisbet’s views on slavery are often considered set in stone—in 1792, he penned a frequently quoted letter in which he predicted that a “Negro war… may probably break out soon” and would do much to further the anti-slavery cause. [4] Perhaps not surprisingly, once he arrived the cantankerous Nisbet made few friends among Dickinson’s majority slaveholder Board. By 1787, one correspondent claimed that “[t]he whole board of Trustees condemn” Nisbet, for having “reflected upon some persons in Carlisle most grossly maliciously and falsely[.]” According to the correspondent, the Duncan family in particular (a slaveholding family) were “very angry” at Nisbet. [5] One important theme of this project will be to discover what was the source of underlying tension between Nisbet and the Board, and if his reputed abolitionist proclivities played any role in estranging him from men such as the slaveholding Duncans and Montgomerys.

Notes

- Power of Attorney from Board of Trustees to William Irvine, January 14, 1799, RG 1/1 Board of Trustees Papers, Series 3, Box 2, Dickinson College Archives & Special Collections.

- Financial Ledger, RG 1/1 Board of Trustees Papers, Series 6, Dickinson College Archives & Special Collections.

- Lisa Rainier, “Benjamin Rush and his Relationship with John Montgomery in the Founding of Dickinson College,” November 15, 1982, Essays, History, Dickinson College Archives & Special Collections.

- Charles Nisbet, quoted in Merton L. Dillon, Slavery Attacked: Southern Slaves and their Allies, 1619-1865, (Baton Rouge: LSU Press, 1990), 48.

- Unknown correspondent to Benjamin Rush, September 1787, Photoduplicate in Benjamin Rush Drop File, Dickinson College Archives and Special Collections.