By Cooper Wingert

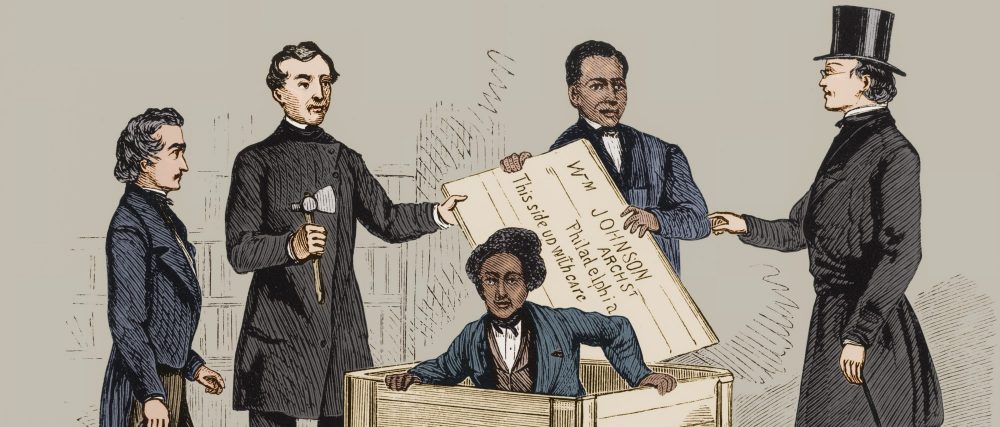

In early December 1837, James Williams, a fugitive slave from Alabama, found his way to a stable near Carlisle, Pennsylvania. At first offering to hire himself out as “a house-servant or coachman,” Williams was met with a chorus of unsympathetic responses—until, that is, a group of black men approached him. “[T]aking me aside,” Williams later recalled, they “told me that they knew that I was from Virginia, by my pronunciation of certain words—that I was probably a runway slave—but that I need not be alarmed, as they were my friends, and would do all in their power to protect me.” With their assistance, Williams was placed in a wagon and driven some fifteen miles to Harrisburg, where he was informed he “should meet with friends.” He would not be safe in Harrisburg, however, but must travel “directly to Philadelphia” and along the way speak to no white man “unless he wore a plain, straight collar on a round coat, and said ‘thee’ and ‘thou.’”[1]

The Narrative of James Williams, An American Slave, published in 1838, remains a controversial (and often discarded) historical resource. Much of what Williams recounted was soon afterwards proved false, and even the abolitionists who had taken down and published his narrative grew uneasy over Williams, labelling him a “doubtful character[.]”[2] Nevertheless, there are teachable moments in observing what Williams chooses to conceal. Further, abolitionist reactions prompt us to reexamine how anti-slavery propaganda was created and defended (or abandoned) against the attacks of pro-slavery Southerners.

The story which Williams had recounted to his African-American “friends” in Carlisle, Quakers on the route to Philadelphia and, ultimately to influential abolitionists in New York such as Lewis Tappan, James Birney and the poet John Greenleaf Whittier, was a heartrending tale of the domestic slave trade. Born and raised in Virginia, James had been a faithful servant who had accompanied his master (and some 200 other slaves) to Alabama, on the pretense that once his master’s affairs were settled in Greene County, Alabama, he too would return home to Virginia. But on reaching Alabama, Williams was “cruelly deceived,” and left behind at the mercy of a hard-drinking, violent overseer. After remaining “for several years,” he had run away in a dramatic escape through the heart of the deep South spanning multiple months.[3]

Soon after its publication, John Beverly Rittenhouse, editor of the Alabama Beacon, a paper published in Greene County, denounced the Narrative as a “lying abolition pamphlet[.]” Rittenhouse was quick to note that no slaveholder of the name given by Williams had recently moved into Greene County. Nor had a sudden arrival of 200 slaves (as described by Williams) been recorded.[4]

In the wake of Rittenhouse’s attacks, much of Williams’ support melted away. Even Whittier, from his new post as editor of the Pennsylvania Freeman (the official organ of the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society), declared that “[o]ur cause needs no support of a doubtful character[.]” Reluctant to discard Williams altogether, he noted that “we are still disposed to give credit in the main to his narrative,” but from a strategic standpoint, backing Williams would give “the slaveholders of Virginia and Alabama” a critical opportunity to assail abolitionist credibility.[5]

John Greenleaf Whittier, an abolitionist poet, took down Williams’ narrative. (National Park Service)

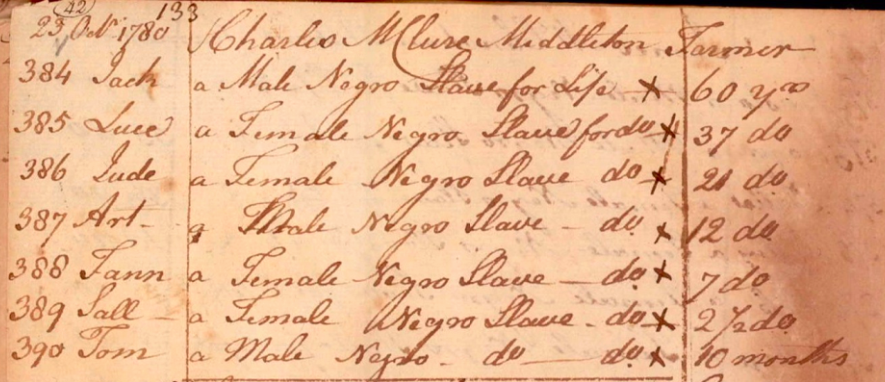

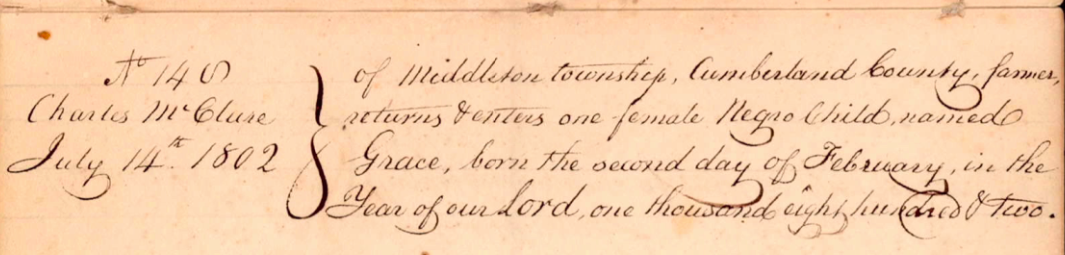

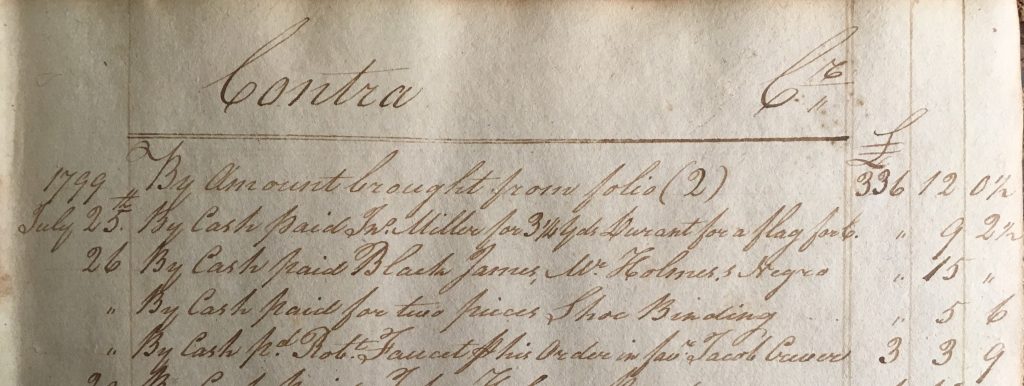

Williams’ account was generally discarded as a fraud, until 2014, when the Narrative was finally reevaluated by researcher Hank Trent. In doing so, Trent was forced to confront a complex reality—he found that while Williams had genuinely been a slave, he had fabricated much of the Narrative. Born as Shadrach Wilkins in Essex County, Virginia, Williams had changed not only his own name, but those of his owners, and the counties in which he resided (Essex County, Virginia, became Powhatan County; Dallas County, Alabama, where he was actually held in slavery, became Greene County). Two reasons prompted these changes—first, Williams’ had been implicated in a scheme to poison the owner of a neighboring plantation. While two other slaves involved were hanged, Williams escaped the noose, and was instead sold south to Alabama. Secondly, Williams sought to cover up his involvement with a huckster. To do so, he changed the date of his escape to the fall of 1837, by which time he was already on free soil. Williams had actually escaped in October 1835, falling in with James B. White, a self-proclaimed abolitionist, although Trent labels him a “con artist.” With White, Williams engaged in a racketeering business—the two travelled, posing as master and slave, with White “selling” Williams into slavery, only to return, aid his escape, and repeat the act at another location. All the while, the two pocketed the money.

Their arrangement unraveled in Baltimore on April 12, 1836, when White sold Williams to James Franklin Purvis, a slave trader. Williams confessed in full, and White was quickly jailed. Returned to his owner’s family, Williams was soon sold, transported to New Orleans, where he was purchased. Intent on freedom, however, Williams made his escape up the Mississippi on the steamer Henry Clay in January 1837, acting the part of a waiter. Once the boat docked near Illinois soil, Williams departed, and disappears from the historical record until the fall of 1837, when he appears in Cincinnati.[6] By early December, Williams was in Carlisle, with a well-developed story of his escape by land through the deep South.

Even falsified, the Narrative offers key insights into abolitionist propaganda. Williams goes to great lengths to portray himself as an obedient servant who was wronged by the slave system, when in fact it was his involvement in a poisoning plot that resulted in his sale south. As portrayed in the narrative, Williams’ story of being “cruelly deceived” by his master was fodder to antislavery activists, cutting right through the heart of Southern paternalistic ideology.[7] The complex truth, however, would not produce such an effect. Williams understood this, and thus incorporated elements of his real life experiences into a framework he felt best suited an anti-slavery message. His breathtaking depictions of going weeks without hearing “the sound even of my own voice,” although placed in a false narrative, came from actual events.[8]

The Narrative also challenges us to reexamine our notions of abolitionists. Williams’ understandable reluctance to disclose his actual life story to the abolitionists he met during the winter of 1837-1838 suggests a more nuanced relationship between anti-slavery activists and the fugitives they helped. Escaped slaves who had something to hide (such as Williams) routinely changed the names, dates and locations of their life stories, to protect against recapture. Abolitionists were faced with the challenge of sifting truth from fiction. In both New York and Boston, Vigilance Committee members trained themselves to spot “discrepancies” in fugitives’ stories that would reveal them as impostors, either seeking money or working as the agents of slaveholders. [9]

Despite its variations between biography and story-telling, Williams’ Narrative challenges us to consider how escaped slaves presented themselves to abolitionists, and also how abolitionists then presented them to the world. It is, therefore, a crucial piece to understanding the production of abolitionist propaganda in the decades leading up to the Civil War.

Notes

[1] James Williams, Narrative of James Williams, An American Slave, who was for Several Years a Driver on a Cotton Plantation in Alabama, (New York: American Anti-Slavery Society, 1838), 97-99.

[2] “Narrative of James Williams,” The Liberator, September 21, 1838, quoting the Pennsylvania Freeman.

[3] Williams, Narrative, 68.

[4] James Williams, Hank Trent (ed.), Narrative of James Williams, An American Slave, (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2014), xviii-xxiii.

[5] “Narrative of James Williams,” The Liberator, September 21, 1838, quoting the Pennsylvania Freeman; for a defense of Williams, see, “Narrative of James Williams,” The Liberator, September 28, 1838.

[6] Williams, Trent (ed.), Narrative, xxvi-xxxv.

[7] Williams, Narrative, 68.

[8] Williams, Narrative, 96.

[9] Eric Foner, Gateway to Freedom: The Hidden History of the Underground Railroad, (New York: W.W. Norton, 2015), 106, 174; John Hope Franklin and Loren Schweninger, Runaway Slaves: Rebels on the Plantation, (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999), 65, 118, 131-132, 289.