This essay originally appeared in Illinois History Teacher 16 (2009), pp. 16-33. It offer a compact overview of how Abraham Lincoln rose to power during the antebellum political crisis.

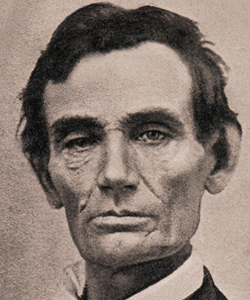

Man of Consequence: Abraham Lincoln in the 1850s

By Matthew Pinsker

“The man who is of neither party is not –cannot be, of any consequence.”

–Abraham Lincoln, July 6, 1852

People tend not to remember Abraham Lincoln as a political party leader. They celebrate him as many things –as president, emancipator, debater, writer, self-made man, folk hero, story-teller, even as a shrewd politician– but few actually focus on the significance of his career as a partisan organizer. Yet Lincoln helped launch the first party system in Illinois during the 1830s and 1840s, played a pivotal role in the formation of the antebellum Republican Party, and might have led a third realignment in American politics if he had only lived long enough to develop the National Union Party, under whose banner he had won reelection in 1864. In particular, it was Lincoln’s decision to organize the Republican Party during the 1850s that transformed his career and helped alter the nature of American political culture.

When the decade began, Abraham Lincoln was a respected former congressman in his early forties looking to rebuild his law practice in Illinois and reconnect with his wife and young sons. Although his experience in Congress had been frustrating, Lincoln had little to complain about. For someone “raised to farm work” as he once put it, the future president had established himself as a successful politician and lawyer with startling ease. Within three years of leaving his father’s farm in Coles County, the young man had been elected to the state legislature (1834) and after just two terms in office had become floor leader for his party caucus. Only a few years removed from the legislature, he then served a single term in Congress (1847-49) where he accomplished little but made some important friends. Meanwhile, despite hardly any formal education, the young politician had taught himself the law, received a license and ended up partnering with two of his state’s leading attorneys before opening his own firm, Lincoln & Herndon, in 1844. He was also married to Mary Todd, the daughter of a prominent Kentucky businessman.

Yet Lincoln still appeared restless and dissatisfied with his political life. Lincoln was a Whig in a state dominated by Democrats. This inconvenient fact limited his prospects for public office. Also, the great economic and constitutional issues that had ignited the formation of the Whig Party in the 1830s seemed less relevant by the early 1850s. But most important, Lincoln was a diligent organizer in a party that resisted organization. He was frustrated by the Whig habit of ignoring basic tenets of nineteenth-century party management. “A house divided against itself cannot stand,” he had warned other Whigs in 1843 while urging them to adopt a convention system for candidate nominations. Since 1849, Lincoln had also been sorely disappointed by the patronage decisions of the new Whig administration in Washington.

Even worse, former local rival Stephen A. Douglas was fast becoming a national phenomenon, the so-called “Little Giant.” In the autumn of 1850, Senator Douglas, still only in his mid-30s, had found a way to rescue the stalled deal over California’s controversial admission to the union. Douglas’s genius lay in realizing that even though the so-called “omnibus” or package bill was doomed to failure because sectional interests outweighed national ones, it was still possible to cobble together a deal by separating the various measures of the “Compromise of 1850” into separate resolutions. Breaking up the compromise into parts allowed southerners to vote against provisions such as the admission of California as a free state, which they opposed, or for northerners to vote against a tougher fugitive slave law, which they despised, because there were just enough swing votes to provide a majority in each case. That is why some historians such as David Potter have described this moment as the “armistice of 1850.”

By that point, however, after nearly two decades of intense agitation over slavery most of the nation’s political leaders were willing to settle for an armistice. On December 23, 1851, vowing “never to make another speech upon the slavery question,” Douglas informed the Senate, “I am heartily tired of the controversy, and I know the country is disgusted with it.” Lincoln did not express himself so bluntly, but he had claimed during the compromise debates that regarding this “one great question of the day” there was “often less real difference in its bearing on the public weal, than there is between the dispute being kept up, or being settled either way” (July 25, 1850). In the 1852 election, both major parties endorsed the measures hoping to see the great debate “settled.”

The Whigs lost the 1852 election but neither party succeeded in upholding the spirit of compromise. Sporadic northern resistance to the new, tougher Fugitive Slave Law increasingly infuriated southerners. The publication of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s anti-slavery novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852) also created a national sensation. For these reasons and others, sectional opinion was becoming more aroused during the early 1850s than ever before. This had a troubling impact on the relationship among states, or what is known in legal doctrine as comity. In the past, for example, many southern states had allowed slaves limited access to their courts for “freedom suits,” or civil actions alleging illegal bondage. The most common ground for a successful freedom suit was proof of residence in free states or territories. Southern courts typically acknowledged that the common law principle of “once free, always free” applied to slaves whose masters had held them in the North, even if they were eventually returned into the South. Yet following the turbulence of the post-compromise period, the Missouri Supreme Court tossed aside decades of precedents in a critical 1852 decision that invalidated the freedom suit of a slave named Dred Scott whose master, an Army surgeon, had once kept him and his wife in military posts in northern territory where slavery had been prohibited.

That is also the principal reason why Stephen Douglas took such a gamble in January 1854 with his controversial proposal to repeal the Missouri Compromise. As chairman of the Senate Committee on Territories and as an ardent believer in westward expansion, Douglas wanted to push through a plan to organize former Louisiana Purchase territories for prospective statehood. However, the always thorny problem of slavery had created a new stalemate. Angry over the failures of the recent compromise and troubled by the breakdown in comity, southern legislators insisted on an explicit repeal of the famous 1820 compromise that had authorized the admission of Missouri into the union as a slave state in exchange for the prohibition of slavery from any other parts of the territory north of the state’s southern boundary (along the 36° 30’ latitude line). In a stunning reversal of his previous position, Douglas agreed to reopen the slavery debate by accepting this repeal and fighting for what he called “popular sovereignty” or allowing territorial residents to decide the slavery question themselves by referendum.

Douglas subsequently convinced fellow Democrat President Franklin Pierce to make the Kansas-Nebraska Act (May 30, 1854) a test of party loyalty. The result was a divisive rupture within the northern Democratic Party and a massive realignment of American politics. Shrewd Whig Party leaders, such as Abraham Lincoln, realized that Douglas’s flip-flop on slavery and hard line party management created an opportunity for them to create an alliance with Anti-Nebraska Democrats. However, the question that historians continue to debate was whether Lincoln and others wanted to revive their flagging Whig Party or create a new kind of party organization.

What makes this question so difficult to resolve are the complicated realities of political life in mid-nineteenth-century America. The Nebraska Bill, as it was known, was by no means the only divisive issue of the day. Northerners, in particular, were experiencing a backlash against European immigration that had spawned a secret nativist or Know-Nothing political movement. There was also a resurgence of “underground” resistance to the federal fugitive slave law, epitomized by the dramatic escape in 1854 of runaway Joshua Glover in Wisconsin and the controversial rendition (or return) of fugitive Anthony Burns from Massachusetts. National politics in that age was also decentralized and could not be fully understood except on a state-by-state, even county-by-county, basis. Finally, politicians themselves were still often reticent about discussing individual political ambitions or behind-the-scenes maneuvers. This inhibition was a legacy from earlier generations of Americans who expected candidates to “stand” rather than “run” for office, because of republican ideology which opposed corrupt power (and power-seeking) and honored civic virtue instead.

Lincoln was not immune to any of these factors. He was friendly with several Know Nothings around Springfield and remained interested in attracting their political followers –though without embracing their principles. Although there was not much Underground Railroad activity in Illinois, there were enough fugitive slave cases to bring Lincoln into court –both as attorney for white masters and for accused runaways. As much as anyone else, Lincoln was also cognizant of local political nuances. During this period, he traveled regularly across a vast portion of Illinois as a circuit-riding attorney. Most important for historians, Lincoln was also the “most secretive –reticent– shut-mouthed man that ever existed,” according to his longtime law partner, William H. Herndon. In various autobiographical sketches written for his presidential campaign, Lincoln characterized his intentions during this period only in the broadest possible terms. “I was losing interest in politics,” he recalled in one example, “when the repeal of the Missouri Compromise aroused me again. What I have done since then is pretty well known” (December 20, 1859).

What Lincoln accomplished during the mid-1850s might have been “well known” but it was not easily understood. In the summer of 1854, he agreed to run for a seat in the state legislature as a way to help promote the local Anti-Nebraska coalition. Yet he spent most of that campaign, as historian Don Fehrenbacher has shrewdly pointed out, speaking outside of his legislative district and with eye apparently toward bigger game, perhaps a seat in the U.S. senate. Lincoln actually traveled the state for a period following Senator Douglas, in effect engaging in a series of informal “debates.” There was neither a statewide nor a local Whig Party convention that year, but Lincoln still occasionally referred to himself as “an old Whig.” However, he also dropped that label whenever it was convenient, and routinely reached out to Anti-Nebraska Democrats, Know Nothings or Free Soilers with little regard for old party allegiances. “Stand with anybody,” he advised Whig audiences during the fall campaign, “that stands right” on the issue of the restoring the Missouri Compromise and containing the spread of slavery.

Here was the essence of the party-building strategy that would eventually carry Lincoln and the Republicans into national power. They kept a single-minded focus on the slavery issue while accommodating as broad a coalition of men as possible. Lincoln helped forge this strategy in Illinois –a critical battleground state in this era– but he has not received much historical credit for these actions. The perception that Lincoln was a reluctant Republican has mostly to do with his hesitation over labels. The all-important 1854 campaigns were chaotic. Across the nation, there were various names for the emerging Democratic opposition –Anti-Nebraska, Fusion, Peoples, or Republican. Illinois was no different, and in some ways, even more complicated. The state was a microcosm of the divided nation, with latitudes (and attitudes about slavery) that stretched from the equivalent of Kentucky to Maine. Thus, when a group of self-appointed “Republicans” from northern Illinois met in Springfield in October and named Lincoln to their central committee, he declined –eager to “stand with anybody” but determined to do so only on his own terms.

Those terms became clear by mid-November 1854 after Douglas and the regular Democrats endured significant setbacks in the fall elections. The Democrats lost two-thirds of their northern congressional seats, and in Illinois, the party lost control of both the state’s congressional delegation and the General Assembly. Sensing this unique opportunity, Lincoln aimed for the U.S. senate seat. In those years, legislatures, not the general public, selected senators; and in the coming year, James Shields, not Stephen Douglas, would be the incumbent Democrat facing reelection. Since Shields was also an Irish immigrant, the ever resourceful Douglas announced that the fight should be over “No Nothingism” and not Nebraska, but Lincoln declined to accept this bait. Instead, he went straight to work, resigning the legislative seat he had won from Sangamon County and directly soliciting votes among the new legislators. Such early and aggressive campaigning for a senate seat was practically unheard of at the time, and nobody else quite matched Lincoln’s zeal or organization.

The determination paid off well at first. By the time the General Assembly opened in January, Lincoln was the frontrunner. He united nearly all of the former Whigs, Know Nothings and Free Soilers into what he labeled in his campaign notebooks as the “Republican organization” (January 1, 1855). But one small group of Anti-Nebraska Democratic legislators refused to caucus with these “Republicans.” The former Democrats held the balance of power. Without their five votes, neither Lincoln nor any Anti-Nebraska candidate could win. But the price for obtaining their support was high. The Anti-Nebraska Democrats insisted that Lyman Trumbull, a congressman from Alton, should be selected as senator. Following several ballots and plenty of high political drama, Lincoln accepted the deal and Trumbull became a United States senator.

Afterwards, Lincoln wrote that he had agreed to Trumbull’s election because he could not “let the whole political result go to ruin, on a point merely personal to myself” (February 9, 1855). However, the result was a personal victory for Lincoln, too. He was not a senator, but he had become an indispensable state party leader. Trumbull’s victory was the first statewide triumph for what would eventually become the Illinois Republican Party, and everyone knew that Abraham Lincoln was the person who engineered it.

The contrast with Stephen Douglas is revealing. As Lincoln was working to unite his new party on principle, Douglas was destroying the Democrats with his endless policy machinations. The doctrine of popular sovereignty in Kansas created a crisis when abolitionists and pro-slavery forces rushed to settle the territory and clashed over how to hold the critical referendum on slavery. Violence erupted and “Bleeding Kansas” became a new symbol of everything that was wrong with the rampant sectionalism of the 1850s. Then, after years of delay, the Supreme Court tried to settle the great national debate over slavery with a ruling in the Dred Scott Case (1857). The infamous verdict denied blacks citizenship and any further access to the courts, discarded old standards of comity on slavery-related matters, and invalidated the Missouri Compromise, claiming that Congress had no constitutional authority to prohibit slavery in the territories. The result encouraged further chaos since the ruling suggested that both slavery containment and popular sovereignty were unconstitutional. Douglas shrugged off this critique and claimed to see vindication in the verdict, but Lincoln was gloomier and found in the court’s decision a distressing sign that an era of compromise had finally passed.

The year 1857 ended with more bad news for Douglas as he broke with the Democratic administration in Washington over the Lecompton Constitution, a patently fraudulent effort by pro-slavery forces to secure Kansas as a slave state. President James Buchanan was willing to accept the “Lecompton swindle,” but Douglas flatly refused. Their rupture sealed the fate of the Democratic Party, but also threatened the future of the Illinois Republicans in an unexpected way. With Douglas cast adrift from the regular Democratic machine, several leading national Republican figures saw this as an opportunity to turn the Little Giant into one of their own. Alarmed by this prospect, Lincoln rallied his forces to resist. He was willing to “stand with anybody” but only when they stood right, and Lincoln claimed he never quite knew where Douglas stood. In June 1858, Illinois Republicans thus broke new political ground by nominating Lincoln in advance of the legislative elections as their “first and only choice” for U.S. senate against incumbent Stephen Douglas.

What followed was a titanic clash of men and ideas. As he had done in a few previous elections, Lincoln began the 1858 campaign by following Douglas and speaking in his wake. This time, however, the two agreed to hold seven joint debates across the state, during which time they engaged in a fascinating exchange about the compatibility of slavery and democracy and the meaning of race and citizenship. By this point, Lincoln was firm in his ideas about the “wrong” of slavery and about the need to put it on a path toward “ultimate extinction.” He was less certain, however, about race. Like most Republicans, Lincoln believed that blacks were human and deserved the “natural rights” of the Declaration, but he was unwilling to commit to any notions of equality or full citizenship. Douglas repeatedly baited him on these issues and was reelected as Democrats managed to retain control of the legislature.

Yet once again, Lincoln benefited from an ostensible defeat. The Lincoln-Douglas Debates earned Lincoln a national audience while also reaffirming his special position as party leader in Illinois. Over the next two years, Lincoln managed to speak in about half the states of the North without losing the loyal support of his peers at home. Nobody else among Illinois Republicans quite matched Lincoln’s combination of managerial skills and communication talents. Nobody else had his record of organizational accomplishment. Nor had anyone had accumulated so much loyalty and respect from others. Thus, by the end of the 1850s, Lincoln had become a man of “consequence” largely because of wise partisan choices. He had not held a single public office during the decade, nor had he won any fame as a military hero –the previous pathways to the presidency. What he had done time and again was to make tough, prudent choices in a confused political climate and to explain them in ways that clarified matters and held a fragile coalition together. That was enough to launch a successful presidential campaign in 1860. It was also enough to suggest that Lincoln had just the right kind of experience for a new and dangerous political era when ballots were sadly giving way to bullets.

Bibliography: Lincoln in the 1850s

Donald, David Herbert. Lincoln. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1995.

Fehrenbacher, Don E. Prelude to Greatness: Lincoln in the 1850’s. Stanford, CA:

Stanford University Press, 1962.

Fehrenbcher, Don E. The Dred Scott Case: Its Significance in American Law and

Politics. New York: Oxford University Press, 1978.

Giennap, William E. Origins of the Republican Party, 1852-1856. New York: Oxford

University Press, 1987.

Guelzo, Allen C. Lincoln and Douglas: The Debates That Defined America. New York:

Simon & Schuster, 2008.

Harris, William C. Lincoln’s Rise to the Presidency. Lawrence: University Press of

Kansas, 2007.

Johannsen, Robert W. Stephen A. Douglas. New York: Oxford University Press, 1973.

Miller, William Lee. Lincoln’s Virtues: An Ethical Biography. New York: Alfred A.

Knopf, 2002.

Potter, David M. The Impending Crisis, 1848-1861. Completed and Edited by Don E.

Fehrenbacher. New York: Harper & Row, 1976.

Waugh, John C. One Man Great Enough: Abraham Lincoln’s Road to Civil War.

Orlando, FL: Harcourt, 2007.