The Secrets of Alexis

Evangeline Clausson

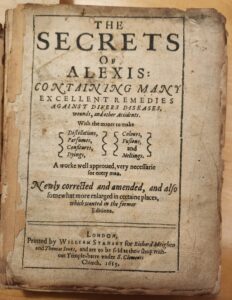

Fig. 1 – Title Page

Vastly popular throughout the mid-16th and early 17th centuries (The Hospital), The Secrets of Alexis is a collection of remedies for any number of ailments and recipes for everything from hair growth and clearing acne to removing stains or making inks. It was published first in 1555 in Venice (in Italian) under the name De’ Secreti del Reverendo Donno Alessio Piemontese (WorldCat). Many editions were published in various languages (The Hospital, 313) over the next several decades, such as this English 1615 edition. The title page expands upon the title, calling it The Secrets of Alexis: containing many excellent remedies against divers diseases, wounds, and other accidents. With the manner to make distillations, parfumes, confitures, dyings, colors, fusions, and meltings. This edition is described as “newly corrected and amended, and also somewhat more enlarged in certaine places, which wanted in the former editions.” It was printed by William Stansby in London for Richard Meighen and Thomas Iones [Jones] [Fig. 1].

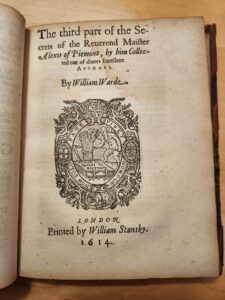

Fig. 2 – Title Page for Part 3

The book is divided into five sections, the middle three having special title pages. These pages accredit William Warde as translator for parts two and three and Richard Androse for the fourth. These pages are dated 1614, suggesting that they had been printed earlier or that the book was re-dated to seem more up to date. They also feature a printer’s device showing a bear and three crests in a border with “NON SOLO PANE VIVET HOMO: Luke 4” (“man shall not live by bread alone”) written on it around a man-dog-angel hybrid with a scythe and wheat standing before a large book which says “bevbum Dei manet in afernum:” (“the child of God remains in the afterlife”) [Fig. 2]. This religious imagery is fitting with the book’s 6 pages of “The Epistle,” which explain how these remedies do not mean to remove suffering or give men the powers of God, but simply to help men live better by the will of God.

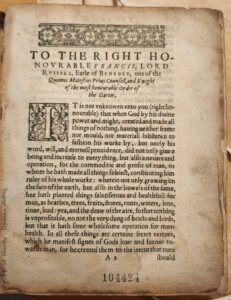

Fig. 3 – Dedication Page

The front matter consists of the epistle, a “to the reader,” and a dedication “To the Right Honovrable Francis, Lord Rvssell, Earle of Bedford” (A2). [Fig. 3] Francis Russell was a royal envoy recieving the Prince of Piedmont in 1554 and then was in Italy in 1555, meaning this dedication wasn’t arbitrary: Russell was a political figure with connections to the author’s home (Dale).

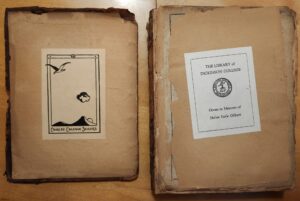

Fig. 4 – Bookplates

This volume features a bookplate showing mountains with a bird and a cloud and the name “Charles Coleman Sellers” at the bottom. Sellers gifted this book to the Dickinson College archives in memory of his late wife, Helen Earle Gilbert, as noted on a Dickinson commemorative bookplate on the adjacent page. [Fig. 4]

Each page is roughly 7.5 inches tall and 5. 63 inches wide. The book is 1.56 inches thick with 348 numbered leaves and 8 unnumbered—6 of the epistle and a blank page at the beginning and end of the volume. The front cover and several of these first pages have become detached from the whole. The volume has also split in two at page 130. The edges of each page are to varying degrees discolored, leaving them a warm brown as compared to the inner-page’s sandy-peach color. Many pages have small dot stains, where perhaps a drop of something had fallen on the page. A few pages have larger areas of discoloration, likely due to a liquid being spilled, though these areas are confined to just a few pages and do not hinder the book’s readability. [Fig. 3]

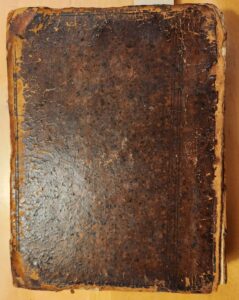

Fig. 5 – Cover

The cover is simple in appearance. It is dark brown and quite splotchy, likely made from mottled calf skin or another variety of leather. [Fig. 5] The only decorative elements are thin black lines pressed into the cover. The edges are frayed, with particularly damaged locations, such as the dent on the outer edge, revealing an almost orange underside of the leather as well as what appears to be pasteboards underneath. The raised bands on the spine indicate it is cord bound. [Fig. 6] The paper is incredibly durable, with only the edges and first few pages, which are more exposed, seeing any deterioration.

The damage as well as few pencil markings bracketing specific passages [Fig. 7] suggest the book was well used at some point, particularly the first half. These pages come apart more easily and the binding feels looser (not just because it’s detached from the main cover, though that may also be a result of its greater use) suggesting that the book was open to these pages more often than those later in the book.

Fig. 6 – Spine

Each page uses two fonts, a basic type font for headings and a variant of blackletter for the recipes. I ran both through two font identifiers (listed below), but I was unable to identify exactly which font either was. The center-aligned headers being in a different font paired with the larger first letter of each remedy helps clarify where sections start and end as the pages are otherwise just remedy after remedy. Occasionally pages have little blocks of printed text in the margins defining or elaborating on terms in the main text.

Fig. 7 – Sample page with pencil brackets

I chose this book because in flipping through, I initially assumed that it was a housekeeping/home remedy guide of some sort, and based on that, I thought it was written by a woman as that is who kept the house, not considering their limited literacy. It is highly unlikely that The Secrets was written by a woman, though wealthy women were known to keep little recipe sets, so it is possible (Bela, 60-61). More likely, however, is that the author was either Girolamo Ruscelli or Alessio Piemontese. As a clergyman and alchemist, Piemontese seems the more probable author, though two late 16th century sources name Ruscelli as the author and that has generally been accepted since (Bela, 53-63). The book is still wonderfully interesting as it gives insight into what daily ailments were and how people tried to solve them, though I am disappointed that the housekeeping-type recipes are largely confined to stain removal.

Works Cited

Bela, Zbigniew. “The Authorship of The Secrets of Alexis of Piemont” Kwartalnik Historii Nauki i Techniki, vol. 61, no. 1, 2016, pp. 52-73. ResearchGate, https://www.researchg ate.net/publication/11726225_Who_really_is_an_author_of_Alexis_of_Piemont’s_secrets.

Dale, M. K. “Russell, Francis (1527-85), of Amersham and Chenies, Bucks. and Russell (Bedford) House, the Strand, Mdx.” The History of Parliament, https://historyofparl iamentonline.org/volume/1509-1558/member/russell-francis-1527-85. Accessed 7 October 2024

“The Secrets of Alexis: containing many excellent remedies against divers diseases, wounds, and other accidents. With the manner to make distillations, parfumes … and meltings …” WorldCat, https://search.worldcat.org/title/5621135. Accessed 3 October 2024.

“The Secrets of Alexis.” The Hospital, vol. 16, no. 407, 1894, pp. 313.

Works Consulted

Ferguson, J. “The Secrets of Alexis. A Sixteenth Century Collection of Medical and Technical Receipts.” Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine vol. 24,2 (1930): 225-46.

Ruscelli, Girolamo. The Secrets of Alexis [Pseud.]: Containing Many Excellent Remedies against Divers Diseases, Wounds, and Other Accidents. With the Manner to Make Distillations, Parfumes … and Meltings … Newly corrected and Amended, and also Somewhat more enlarged in certaine places, Which wanted in the former editions., Printed by W. Stansby for R. Meighen, 1615.

“The Secrets of Alexis [pseud.]” Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/49043523/. Accessed 3 October 2024

Font Identifiers Used

What the Font: https://www.myfonts.com/pages/whatthefont

Font Squirrel: https://www.fontsquirrel.com/matcherator

Leave a Reply