Figure 1: The Spine

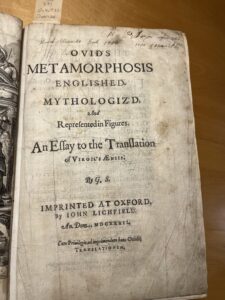

George Sandys’ 1632 edition of Ovid’s Metamorphoses stands out within his oeuvre for one reason—its beautifully drawn illustrations. From the binding, one would never know that the book contained sixteen full-sized lithographs, each exquisitely detailed and depicting a different story from Metamorphoses. The spine reads Ovid’s Metamorphosis, but the title page states the full title as Ovid’s Metamorphosis Englished, Mythologiz’d, and Represented in Figures. An Essay to the Translation of Virgil’s Ӕneis, finally clueing readers into the splendor of the book (See Figures 1 and 2). Frances Clein designed the lithographs, which Salmon Savery then implemented (Ellison). John Lichfield, an experienced publisher at Oxford University, published this edition. Only his name is credited alongside Sandys’ on the title page.

Figure 2: The Title Page

This copy of Metamorphoses had many oddities, most of which lie in its formatting. Sandys’ translation is a large, heavy folio, far taller and wider than any book I have ever owned. It contains 549 pages, but there are multiple mistakes regarding the pagination that beg the question of what exactly happened during printing. There are two sections in the text where the numbers skip, omitting pages 47-50 and 122-144. The first instance of missing pages may very well have been a simple mistake as the result of human error and oversight. But the second instance—skipping 22 entire pages—is much harder to ignore. How does such an error happen? Adding to the oddity of it all, the actual story itself does not skip. The text of Metamorphoses flows continuously from page 121 to 145 with the correct catchwords and signatures. By all accounts, no physical pages are missing. The binding remains firmly intact and there are no remnants of pages destroyed or removed. It seems more likely than anything that it is a case of mistype, but again, such an egregious error makes one wonder how no one caught it before it went to print. John Lichfield had worked as Oxford’s printer since 1617, making him a veteran of the craft (Roberts). To have a book he published and printed contain such an error would be almost unthinkable, but in all likelihood we may never know the true circumstances of how the pagination came to be so incorrect.

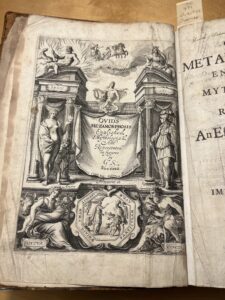

Figure 3: The Frontispiece

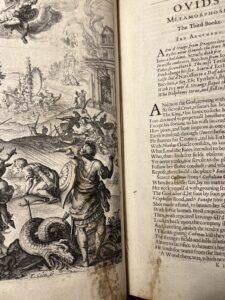

Before the actual text of Ovid’s work begins, there are 10 pages of front matter. The text is then separated into fifteen books, followed by a translation of Virgil’s Ӕneis. The black and white illustrations accompany each of the fifteen books depicting their respective myths, but the Aeneid does not have its own illustration. The sixteenth illustration is the elaborate frontispiece alongside the title page (Figure 3). The illustrations themselves are lithographs, evident by the impressions on the backside of each illustration. The pages are in good condition, and all the illustrations are intact except for one. The illustration accompanying book three has a noticeable tear starting in the bottom right corner that extends to nearly half the page. It is poorly taped in the back, and the illustrated side has brown lines and markings along the tear that bled onto the first page of book three (Figure 4).

Figure 4: The ill-repaired tear at the beginning of Book 3

The paper itself has held up well over the centuries, with only a few spots of mildew and occasional stains scattered throughout. The paper has a slight thickness to it and it is smooth and flexible. Based on the date of publication, the pages are most likely cloth-based, made from rag or hemp. I do not have personal experience with telling types of paper through touch, but the Dickinson College Special Collections Librarian, Malinda Triller-Doran, also assessed the pages and confirmed the paper is cloth-based. The binding is calfskin, indicated by its smooth texture and dark brown color. I compared Ovid’s Metamorphosis Englished, Mythologiz’d, and Represented in Figures to other texts in the Archives & Special Collections that were bound in vellum, calfskin, and pigskin as confirmation.

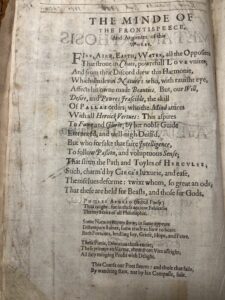

Figure 5: “The Minde of the Frontispiece”

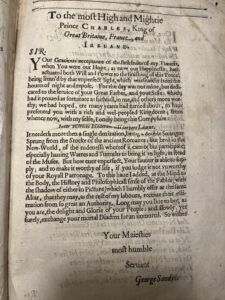

A unique characteristic of this text is the amount of front matter and paratexts it holds. After the frontispiece and title page, there is an explanation of the frontispiece titled “The Minde of the Frontispeece, and Argument of this Worke” (Figure 5). Following this, there is dedication from Sandys to King Charles I (Figure 6), a panegyric to King Charles I, an address from mythological figure Urania to Queen Henrietta Maria, an address to the reader, and finally two sections on Ovid: “The Life of Ovid” and the aforementioned “Ovid Defended.” Throughout the paratexts are references to Greek myths Ovid included in Metamorphoses, such as those of Circe, Hercules, and of Echo and Narcissus. I found it interesting that Sandys included both a dedication to Charles I and a speech of praise addressed to him. To include both seemed to be excessive, so it is possible that Sandys was trying to curry favor with the king. I was not familiar with the word “panegyric” until reading it here, but upon learning its definition, I understood why Sandys included it in the front matter.

Figure 6: Sandys’ personal dedication to King Charles I

As mentioned previously, the pages and actual text of the book are well-preserved, but the binding is a different matter. The spine is in good condition, but the cover has some severe wear. It suggests that the book was either well-loved or improperly stored, possibly both. Both the front and back covers have discoloration and deep gouges, exposing the board of the book in multiple spots. There is also a stain on the backside of the leather. Different-sized splotches litter the fore edge, matching the external wear on the rest of the book. The text does feature some inscriptions, particularly on the title page. Someone wrote the name Thomas Chadwick alongside the word “Book” and “1780”—likely Mr. Chadwick himself. There is also illegible text written in brown ink above the name. On the flyleaf, in pencil, someone wrote £2.10, suggesting the book sold for that price at some point, but it is impossible to discern when. Ideally, I will be able to uncover more about the book’s history in Part II: Origins, along with the mysteries of the pagination and Sandys’ considerable devotion to King Charles I.

Works Cited:

Ellison, James. “Sandys, George (1578–1644), writer and traveller.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. January 03, 2008. Oxford University Press.

Roberts, R. Julian. “Lichfield, Leonard (bap. 1604, d. 1657), printer.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. September 23, 2004. Oxford University Press.

Leave a Reply