French Cookery, The Modern Cook, a Practical Guide to Culinary Art in All its Branches, by Charles Elme Francatelli, stuck out to me out of a myriad of other books. It’s a cookbook, and therefore, it stuck out to me because of the rich history a cookbook can hold. I am very interested in studying and working closely with a book that families would have relied on to cook meals. The content of the book intrigues me as the recipes are very universal. Some are for Indian food, some are French recipes, and some are for filets and other meals that are still very popular. Some of the recipes are rare, like turtle soup, and some still hold up, such as the section on beef roasts. This book has a lot of really interesting recipes that show the book’s age as well as indicators of its past life as a functional recipe book.

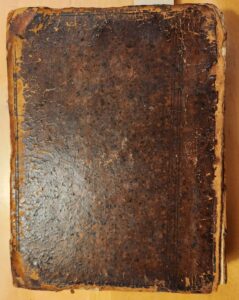

The book’s cover does not include the book’s name or any text in general (see Figure 1). The cover, however, has a golden illustration that looks like a stamp. It is the image of a platter of food with a bowl in the center with serving instruments poking out of the food. It has been indented into the book. It feels like it’s been embedded into the cover as it is bumpy to the touch; the foil, however, feels very smooth. The cover also includes a border called a blind. The blind is in a floral pattern like a vine. Unlike the stamp, this is raised instead of embedded into the cover. Part of the name is included on the spine. The spine says: French Cookery by Francatelli, with another golden image of a similar yet different platter of food. The first time the whole title appears is on the title page.

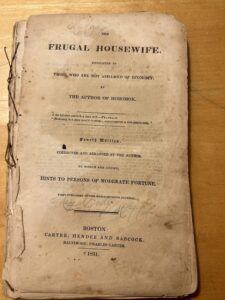

The title page includes more information, stating that the cookbook has been “Adapted as well for the largest establishments as for the use of private families.” Under the author’s name, he gave credit to his mentor, saying, “Pupil of the celebrated careme and late mater d’hôtel and chief cook to her majesty the queen.” The title page includes “with numerous illustrations.” Lastly, the title page states that this book was published in Philadelphia by Lea and Blanchard in 1846 (see Figure 2). Two separate editions were published, one being the “London Edition.” It states nowhere that this is the London edition, so assumably, this is the other edition. There is no editor credited, and since this is a cookbook of a very accomplished chef, there most likely wasn’t one. This book also includes a forward, an index, and a glossary. The book includes 588 pages total, including blank pages. Of the 588 pages, 576 of these pages had type on them, and 540 pages of this book were recipes. In total, there are 1447 recipes included in this cookbook. The physical book is 10 inches high, 6.5 inches long, and 1.5 inches wide.

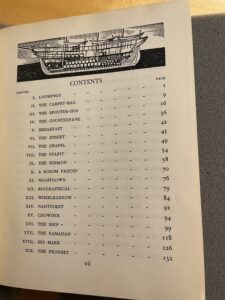

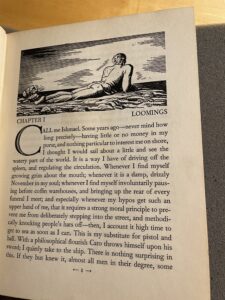

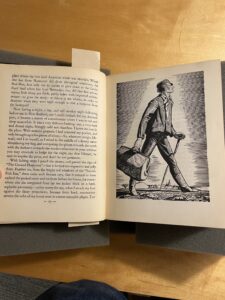

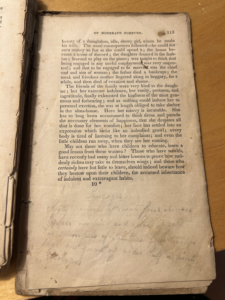

This book is made with fairly high-quality paper. All but three pages are still fully intact. The paper is thick, and the only damage is on the edges of the page. The binding is made of cloth bound by glue and string (see Figure 3). This is clear because the bottom of the spine has started to break and separate from the cover. You can see the cover and the cloth starting to peak out of the bottom. I could not determine the font; however, the qualities are similar to Times New Roman; the letters have similar head serifs. This cookbook includes multiple illustrations. Every illustration is in the same design as the cover illustration, without the gold coloring; they are all in black and white (see Figure 4). They all depict serving platters or suggest proper servings for certain recipes. In total, there are 55-60 illustrations accompanying the recipes. The end of the book includes 36 pages of advertisements (see Figure 5). Most of these advertisements include images, and they all are for other lifestyle books.

The book is broken up into chapters and sub-chapters. At the beginning of a chapter, the general recipe types are laid out under the title of the section. Each page that includes recipes has a very consistent layout. Each recipe is titled in an italicized font, and the recipe is a paragraph describing the steps and ingredients needed for the dish; this does not include any measurements. If there is an illustration, it is under the recipe. When a new sub-section is introduced, it is separated from the previous section by a squiggly black line. Each page is headed by what type of recipe is on the page. Some recipes have a note at the bottom of the page indicated by an asterisk. Some other discrepancies from the typical layout are later recipes that refer back to the earlier ones (such as sauces), using parenthesis to indicate this. Near the end of the book, before the advertisements, there is a section of recipes correlating to a day a year; these also break the typical layout. There are different ideas for meals based on the day of the year, in total, there are 365 meal ideas.

The recipe book feels very used and loved. The pages are oily, which reminds me of my grandmother’s old cookbooks that have cooking oil on each page. This book has clearly been used for cooking. A handful of pages are dog-eared, which indicates that these pages include recipes that the original owner frequently used. It’s a sturdy book, which is good for a cookbook as these books endure a lot. If being used in a kitchen, it’s going to be around food, fire, and other things that can hurt the book if it’s not durable. It’s not that heavy, however, which is another quality that is good for a cookbook because whilst cooking, books get moved around frequently. The book is intended for domestic use as well as professional; the title page states its intended use. A few pages of the book have started separating from the binding, showing its age. Reading and touching the book as an artifact feels a bit wrong. It seems very intimate as this was used by someone who appreciated the recipes and presumably cooked for their family. It also feels very nostalgic as it transports me to a time when I would cook with my family.

The book includes a signature on the title page, belonging to a Mrs. B. Stilingfleck (see Figure 2). This is the only writing in the book that is not the original text. Every page has light brown stains; these stains are mildew due to aging and the way it was stored. This is called foxing and is common in old books. On page 475, there is a very small amount of crushed-up brown powder that resembles coffee grounds. This substance created an oil that seeped through and stained the next four pages. Between pages 42 and 43, there is a long, frayed gold fabric coming from the spine (see Figure 6). I believe this is part of the binding that has started to unravel. Lastly, as mentioned before, three pages (273, 392, 393) of the book are torn on the sides. Each page is torn similarly it can be assumed that this was an error in the book-making process. It looks as if the pages weren’t cut, and the owner cut them after buying it.

Works Used:

French Cookery, The Modern Cook, a Practical Guide to Culinary Art in All its Branches, by Charles Elme Francatelli