Authors do not write books in a vacuum. As Michel Foucault theorized, authors craft books within a capitalist market framework that guides them to write first and foremost to sell their work, as seen with the previous examinations of David Humphreys’ 1730 book as a material work and historical item (Foucault, 291). In this sense, authors explicitly construct their books for their intended audience, oftentimes prospective buyers. In the case of the 1730 work An Historical Account of the Incorporated Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts Containing their Foundation, Proceedings, and the Succeses of their Missionaries in the British Colonies, to the Year 1728 the author addressed British King George II to maintain royal funding for the Incorporated Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts. The author, David Humphreys, was an active member of the Society who composed the work on behalf of the organization. The organization organized missionary efforts in the British colonies in North America, evangelizing mainline Anglican Christianity at a time of continued royal concern over Catholicism. As recently as 1700, the English Parliament mandated that all English monarchs be Protestant and explicitly forbade Catholics from ascending to the throne (Act of Settlement).

In the milieu of continued religious fervor and a growing British empire in North America, the Incorporated Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts served the royal goal of advancing Protestantism in the colonies. So important was this Georgian conversion objective that King George II and his predecessor King George I personally funded the Society. In fact, most of the Society’s funding originated from royal coffers, only supplemented by income from a Barbados plantation (Humphreys, vi-vii). Given the financial situation of the Society, Humphreys wrote An Historical Account of the Incorporated Society to justify the organization’s work to its primary donor: King George II. In the introduction, Humphreys clearly states the goal of An Historical Account of the Incorporated Society by noting “It is hoped that the reader upon peru[s]ing the following Papers, will find Cau[s]e to be much plea[s]ed with the unexpected Succe[s]s of [s]o great a Work. E[s]pecially if it is con[s]idered, that this Society hath no publick Income or Revenue.” (iv-v). Humphreys goes so far as record the Society’s missions in North America as “royal intentions” (xxx).

Despite Humphreys’ intention of justifying continued royal funding for the Society’s mission in North America, this copy of An Historical Account of the Incorporated Society’s primary audience became students at Dickinson College in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, nearly four thousand miles from London. Between the 1730s and 1760s, Isaac Norris Jr., the son of Philadelphia politician, merchant, and noted book collector in his own right Isaac Norris Sr. acquired An Historical Account of the Incorporated Society. The book passed to Isaac Norris Jr.’s daughter Mary after Isaac’s death in 1766 (Korey, 8). Mary married John Dickinson, the namesake of Dickinson College, who in turn obtained An Historical Account of the Incorporated Society alongside the hundreds of other books Isaac Norris Sr. amassed. John Dickinson donated the work to Dickinson College in 1784 (Korey, 21).

Until 1934, An Historical Account of the Incorporated Society was accessible for Dickinson students and faculty at the normal shelves of the Dickinson College Library. Instead of King George II, young Dickinson College students read An Historical Account of the Incorporated Society. These students (including myself) read the work to learn about the religious demography of early modern North America and how the British elite viewed North America from a religious perspective. Many of these Dickinson students likely studied theology, especially in the nineteenth century as the Second Great Awakening spurred religious fervor on Dickinson College campus in particular (Revival of Religion).

Undoubtedly, numerous students read the book across centuries, as indicated by the poor condition the tome exists in today. No front cover remains, and few parts of the spine endure. There is no physical evidence of repairs to the book, indicating that after its move to the Dickinson College Archives in the 1930s, conservators prioritized repairing/rebinding other more well-known works or those in even worse condition instead. In the future, a new audience may emerge for An Historical Account of the Incorporated Society, possibly scholars focusing on eighteenth century British/North American religious history rather than King George II or Dickinson College students.

Works Cited

“Act of Settlement” UK Parliament. Accessed 1 December 2024.

legislation.gov.uk/aep/Will3/12-13/2/data.pdf.

Foucault, Michel. “What is an Author?.” The Book History Reader, edited by David Finkelstein

and Alistair McCleery, Routledge, 2002.

Humphreys, David. An Historical Account of the Incorporated Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts Containing their Foundation, Proceedings, and the Succeses of their Missionaries in the British Colonies, to the Year 1728. London: The Incorporated Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts, 1730.

Korey, Marie Elena. The Books of Isaac Norris (1701-1766) at Dickinson College. Carlisle, PA, Dickinson College, 1975/1976.

“Revival of Religion.” The Religious Intelligencer, 18 Jan. 1823,

proquest.com/docview/137429704/pageviewPDF/A2297C93E1CB46F4PQ/1?accountid=10506&sourcetype=Magazines. Accessed 15 October 2024.

Author: Ryan Bergh Thies

Every book we read is a material item, and just like artifacts of the past, they have extensive histories often stretching back decades before we read their pages. An Historical Account of the Incorporated Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts Containing their Foundation, Proceedings, and the Succeses of their Missionaries in the British Colonies, to the Year 1728 is no different. David Humphreys wrote the book to describe the royal-funded Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts’ efforts to evangelize in the British North American colonies. Joseph Downing printed An Historical Account of the Incorporated Society (title shortened) in 1730 in his Bartholomew-Close, London, print shop. Downing was a close associate of the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts which provided him a steady income in the book printing industry in the first decades of the eighteenth century (Jefcoate, doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/53804). Outside of working for the Society, Downing was a prolific printer in his own right, even printing translated German texts. Downing died in 1734, but his work and connection to the Society in London continued under his widow’s supervision.

Downing’s printing of An Historical Account of the Incorporated Society lived on past his death, with the work eventually travelling across the Atlantic Ocean to the Thirteen Colonies that David Humphreys investigated in when writing the work in 1730. Between the 1690s and his death in 1735, Philadelphia politician and merchant Isaac Norris collected an array of books, particularly about scientific works (Korey, 2). Given the fact that Norris Sr. died only five years after Downing printed An Historical Account of the Incorporated Society, the work likely came into the Dickinson College Library’s “Norris Collection” through his equally intellectually invested son Isaac Norris Jr. Born in 1701, Norris Jr. amassed a vast personal library by the 1760s, including prominent literary works such as John Milton’s Paradise Lost (Korey, 7). Norris accumulated scientific works as his father initiated, but also collected North American-specific works on the history of the Thirteen Colonies such as Humphrey’s book. In an indication of elite Enlightenment polyglotism in North America, Norris’ titles were primarily non-English books, written in French, German, Greek, Latin, Dutch, and Italian (Korey, 9). In his introduction for the 1975/1976 The Books of Isaac Norris (1701-1766) at Dickinson College, Edwin Wolf derides the few English works as “relatively unimportant theological works,” which undeniably includes the English theological work An Historical Account of the Incorporated Society. Most importantly, Norris Jr. collected contemporary works (those published in the mid-eighteenth century like An Historical Account of the Incorporated Society) in particular, ordering copies of freshly printed books. Norris held only a handful of pre-1700 works in English (Korey, 10). Norris read many of the 1,902 books (1,750 volumes) in his collection, etching notes in the introductory flyleaves (Korey, 13). No such notes exist in An Historical Account of the Incorporated Society, so it is difficult to assess if Norris read the 1730 work. However, once the book travelled to Dickinson College, it likely became a staple textbook of the institution.

After Norris’ death in 1766, the collection passed to his son-in-law John Dickinson (Korey, 8). Humphrey’s 1730 work was part of this, in the words of John Adams “very grand,” collection. In 1784 John Dickinson, the namesake of Dickinson College, donated the Norris Collection to Dickinson College (Korey, 21). The Norris Collection formed the core of the early Dickinson College Library, contributing to one of the most extensive educational libraries in the new nation, larger than those at more established institutions such as Yale. An Historical Account of the Incorporated Society was one of these 2,700 volumes that graced the normal shelves of the Dickinson College Library from 1784 to 1934 (Korey, 16, 19). However, by 1975/1976 An Historical Account of the Incorporated Society was in poor physical condition after centuries of use (Korey, 160). No front cover existed, an unusually prominent mark of damage compared with the reports of other Norris Collection works in generally average quality.

In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, Christian theology played a vital role in the pedagogy of Dickinson College. In fact, Benjamin Rush in part chartered Dickinson College to counter the intellectual supremacy of radical Philadelphia Presbyterians in Pennsylvania (Korey, 1). Given An Historical Account of the Incorporated Society’s placement on the regular Dickinson College Library shelves alongside more modern works for 150 years and the close connection between Dickinson College’s religious foundations and the book’s study of eighteenth-century religion, it is undeniable that Dickinson College students handled the work frequently even centuries after its publication.

The copy in the Norris Collection is not the only edition surviving today. According to WorldCat.org, Downing printed editions of An Historical Account of the Incorporated Society in 1720 and 1728 (search.worldcat.org/formats-editions/10536619?limit=50&offset=1). As late as 1967, an unknown printer re-printed a modern copy of the work in microfilm (search.worldcat.org/title/1127677992). Today, numerous copies of Downings’ 1730 printing abound in online stores. On the Bauman Rare Books website, the work has a sale price of $3,800 (baumanrarebooks.com/rare-books/humphreys-david/historical-account/91250.aspx). Even if the work no longer graces the shelves of the Dickinson College Library today, readers continue to purchase it across the globe.

Works Cited

“An historical account of the incorporated Society for the propagation of the gospel in foreign parts: containing their foundation, proceedings, and the success of their missionaries in the British colonies, to the year 1728.” World Cat. search.worldcat.org/formats-editions/10536619?limit=50&offset=1. Accessed 6 November 2024.

“An historical account of the incorporated Society for the propagation of the gospel in foreign parts: containing their foundation, proceedings, and the success of their missionaries in the British colonies, to the year 1728.” World Cat. search.worldcat.org/title/1127677992. Accessed 6 November 2024.

“Historical Account.” Bauman Rare Books. baumanrarebooks.com/rare-books/humphreys- david/historical-account/91250.aspx. Accessed 4 November 2024.

Jefcoate, Graham. “Downing, Joseph.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. 23 September 2004. doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/53804. Accessed 3 November 2024.

Korey, Marie Elena. The Books of Isaac Norris (1701-1766) at Dickinson College. Carlisle, PA, Dickinson College, 1975/1976.

Today, the books we read are generally new, printed within the last fifty years and in good condition. How will these books we read today look in three hundred years? An Historical Account of the Incorporated Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts Containing their Foundation, Proceedings, and the Succeses of their Missionaries in the British Colonies, to the Year 1728 was an exceptionally high-quality book when first published. After nearly three centuries of use at Dickinson College, parts of the book are in a pitiful state.

As a religion minor, I choose to study this book as I have an interest in early modern religious history, especially the Reformation and British faith disputes in the sixteenth, seventeenth, and eighteenth centuries. I feel that I can learn more not only about early eighteenth-century English Christianity, but also its confluence with London’s colonial policies in North America. I am likely not the first Dickinson student to glance upon its pages. Dickinson has a long tradition as a Presbyterian and then Methodist religious institution, with contemporary publications noting the religious fervor of Dickinson as early as 1823 (“Revival of Religion,” 536). Quite possibly, religion students read the work to learn about the religious demography of early modern North America.

David Humphreys, a Doctor of Divinity and secretary to the Incorporated Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts, wrote An Historical Account of the Incorporated Society (title shortened). In 1730 Jospeh Downing printed the work in Bartholomew-Close, London. The book measures in at approximately 5 inches (12.7 centimeters) of width, 7.5 inches (19 centimeters) of height, and 1.5 inches (3.8 centimeters) in depth. The page count is 356 numbered pages, 31 introduction pages, and 3 non-numbered pages for a total of 195 sturdy sheets. These dimensions roughly align with those of modern books, albeit with a large page count for the small binding that potentially overburdened the binding. The thick paper is superb quality—dare I say better than the modern paper of our textbooks—and easy to handle. The binding is calf skin and although the rear cover is intact, the front cover no longer exists after centuries of use. With close examination, readers can see faint horizontal lines across each page in areas without text, likely the “chain marks” from hand-made paper production. After centuries of use, the work’s pages are still readable and durable, a testament to the quality of hand-made paper compared to later nineteenth century machine-made paper (Clapperton, 15).

Fig. 1: Spinal binding

Sadly, the binding is in much poorer condition. It is precarious holding Humphrey’s work; so little of the binding remains that pages could easily become torn from the book if readers are not delicate. The binding looks to be composed of leather, with a white string used in the spinal binding (See Fig. 1).

Fig. 2: Signature page marking

The book is no longer one complete work. Rather, the binding splits in different locations (beginning at the map page), creating separate sections of pages bound together. Characteristic of the printing process, most pages include “signature page marks” where a letter represents each section, with each page of the section numbered (See Fig. 2).

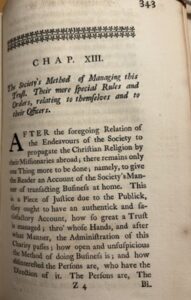

The book’s ink is well-preserved, with no prominent ink splotches or bleeds on the paper. The typeface is characteristic of other early modern books. The type setters chose to primarily employ the Letterpress Text font, but some sections (chapter titles in particular) are Italique 1557 (myfonts.com/pages/whatthefont). Almost every page contains certain special italicized words, such as Briti[s]h (See Fig. 3).

Fig. 3: Italicized words

One aspect of the text that may baffle readers is the absence of the letter ‘s.’ Rather than using s in words, Humphreys chose to use f, spelling words such as Christian as Chriftian (as seen in the above image). Despite what readers may perceive today, the “long s” Humphreys employs is simply a different letter model for s, rather than the letter f. Save for this different model for s, the book is easy to read for readers such as myself and previous students.

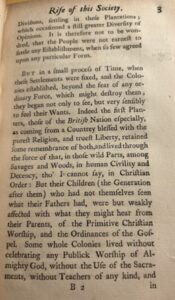

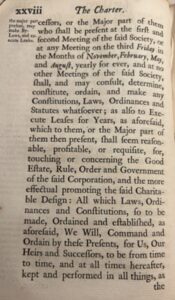

The arrangement of text in An Historical Account of the Incorporated Society is intriguing. Marginal notes abound on virtually every page. Downing printed these numerous small notes next to the larger text rather than writing any by hand. These marginal additions provide brief context on the topics discussed in the text as in this image that clarifies that changes to the “bylaws and lea[s]es” of the Incorporated Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts to require a majority quorum of voting members (See Fig. 4).

Fig. 4: Marginal text

Some marginal notes appear to be portions of the text that went unprinted initially, but others are simple comments and do not seem to fit within the larger text. Perhaps Jospeh Downing printed the marginal notes both to add new comments and include sentences missed in the initial printing. Some pages contain catchwords that assist printers by indicating the next page’s first word (See Fig. 5). Numerous pages throughout the book display black and white ornamental illustrations (not images). Decorative border pieces adorn the beginning and end of chapters (See Fig. 6).

Fig. 6: Decorative border

Fig. 5: Catch words

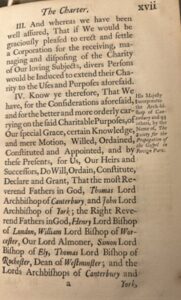

Fig. 7: Fleur-de-lis

Smaller fleurs-de-lis create boundaries between different sections/chapters on the same page (See Fig. 7). The most recognizable illustration is the royal seal of England. The seal appears at the beginning of the Charter/preface section, meant to lay out the goals of the Society and thank the monarchs William III (who assisted in founding the society) and George II (the British king in 1730). These numerous illustrations and gold lining along the edges of the rear cover indicate the significant financial investment made by the Society into printing a visually stunning book that retains its beauty today even without a functional binding.

The work came to Dickinson College from the collection of well-regarded eighteenth-century Philadelphia politician and businessman Isaac Norris. The Norris Collection holds nearly two thousand books on numerous intellectual topics. Mary Dickinson and her husband John donated the collection to Dickinson College in 1783, the same year the college opened. I am excited to continue the work of previous students in unpacking this beautiful book brought to Dickinson College 241 years ago.

Works Cited

Clapperton, R.H. The Paper-making Machine: Its Invention, Evolution, and Development.

Google Books E-Book, Pergamon Press, 1967.

“Revival of Religion.” The Religious Intelligencer, 18 Jan. 1823,

proquest.com/docview/137429704/pageviewPDF/A2297C93E1CB46F4PQ/1?

accountid=10506&sourcetype=Magazines. Accessed 15 October 2024.

“What the Font?” My Fonts, myfonts.com/pages/whatthefont. Accessed 23 September 2024.