Ai Lettori: To the Readers

Who were these readers?

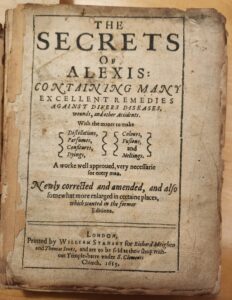

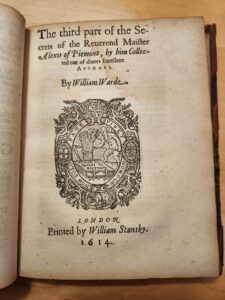

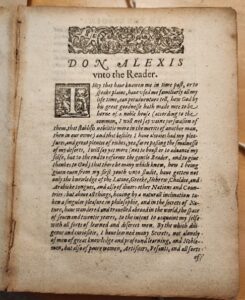

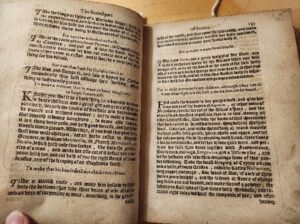

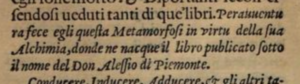

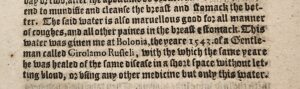

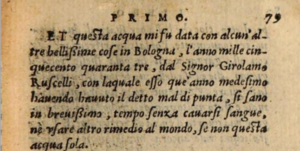

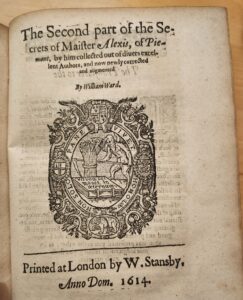

I am studying a 1615 English Edition of The Secrets of Alexis. The book was originally published in Italian under the name De’ Secreti del Reverendo Donno Alessio Piemontese in 1555 (WorldCat). This book was printed by William Stansby in London. It is a book of recipes for medicines, dyes, cosmetics, alchemy, etc. For more information on the physical book or the people who helped make it, please see my previous posts The Secrets of Alexis and The Secrets of … Who?.

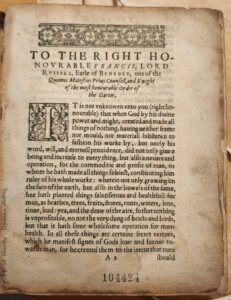

In my last post, I looked at the “To the Reader” and the way the author describes himself in it. This time, I want to look at how he views the reader, or rather, readers. In the Italian, this section is titled “Ai Lettori,” meaning “To the Readers,” the “i” at the end of both words indicating plural readers. With the vast popularity of the book, I feel the Italian offers a more fitting heading.

Alessio spent his life collecting these “secrets,” reaching a point where he was “assured that few other men [had] so many as” him. He had originally kept these recipes secret because out of “ambition and vain glory, to know that which another should be ignorant of.” He changed his mind, however, after a man had died of something he might have cured because he was too proud to share the remedy, and the physician was too vain to let another man help his patient. He wanted these “secrets” made public so that no one else would die in vain. In this way, his target audience is everyone and anyone possible—as many people as possible.

With so many print runs in so many languages, The Secrets of Alexis was certainly successful in reaching a wide audience. In 1894, an article from The Hospital notes how people would carry copies cheaply bound in blue paper with them to country fairs and such from the mid-16th into the early 17th century. This indicates, firstly, that the book was a staple for home remedies and amateur alchemy for almost half a century, and secondly, that historians have used The Secrets study the medical understanding of people at the time of its publication and the peak of its popularity. In a way, the historians are another, though unanticipated, audience of the book.

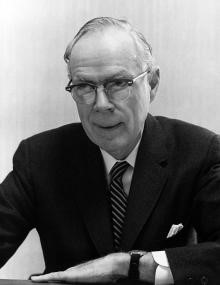

Charles C. Sellers, c.1970

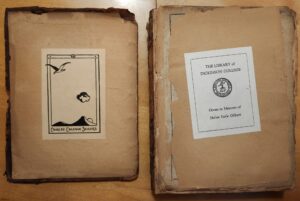

As for this specific copy, I know for certain of only two owners: Dickinson College and Charles Coleman Sellers. Sellers was born in Overbrook, Pennsylvania March 16th, 1903. He attended Haverford College, graduating in 1925, and then earned his Master of Arts at Harvard the following year. In 1957, he received his doctorate from Temple University. He worked as a historian and a librarian for various libraries and institutions. These include Wesleyan University (1937-1949), American Philosophic Society of Philadelphia (1947-1951), Dickinson College (1949-1969), and Waldron Pheonix Belknap Jr. Research Library of American Painting (1956-1958). He was also the editor for the American Colonial Painting (1959), as well as an esteemed author. Much of his work focused on early United States art history. He published three books on Charles Willson Peale in 1947, 1952, and 1969, as well as Benjamin Franklin in Portraiture (1962) Dickinson College: A History (1973), and Patience Wright (1976). Sellers was married twice. His first wife was actress Helen Earle Gilbert (m. 1932-1951), whom this volume was donated in memory of. In 1952, after Gilbert’s passing, Sellers married Barbra S. Roberts.

This book was donated at some point between his first wife’s passing in 1951 and his own passing in 1980. There does not appear to be any further information on Sellers and how he got The Secrets, what he thought about it, when or why he donated it to the college, etc. It seems that because he worked in the archives, he felt such fanfare for his own donations were unnecessary, much to my dismay.

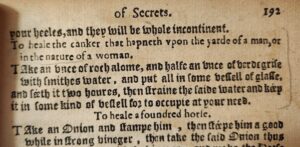

I imagine Sellers was not the first nor only owner of this book because it was printed nearly three centuries before he was born. Moreover, I noticed pencil markings on several pages, drawing attention to specific recipes. These markings may have been made by Sellers, but because of a trend I noticed in these recipes—that more than a third of them relate to sexual issues (menstruation, pregnancy, boils on the groin, etc.)—I think the book may have been read by someone researching or interested in the history of people’s understanding of sexual health. This would most certainly not be the audience that Alessio intended The Secrets for because these recipes were supposedly added in later additions, likely by a publisher or William Ward while he was translating the work to English (Martins). Also, I think this “other reader” was a woman because they underlined “in the nature of” referring to a woman, highlighting the difference in the way men and women were described in this remedy.

Interestingly, the pencil markings are mostly in the second part of the book, meaning more recipes relating to sexual health in the third part were not marked. The other recipes marked look at various topics: serpents, lizards, dogs, sunblock, warts, wild beasts, “marvelous dreams” etc. It is possible that these recipes were marked because they seemed a little impractical or impossible and the reader was amused by them. Branches put in a person’s ears, for example, do not prevent sunburn on the top of a person’s head. The trend I noticed above might actually be coincidence, and so many of these recipes were marked because there was so much faulty understanding about this topic, especially about women. A toad tied to a woman’s neck will not end her menstruation quicker, nor will any herb make a woman more likely to bear sons than daughters.

Works Cited

“Charles Coleman Sellers (1903-1980).” Dickinson College Archives & Special Collections, 2005. https://archives.dickinson.edu/people/charles-coleman-sellers-1903-1980. Accessed 2 December 2024

“De’ secreti del reverendo Donno Alessio Piemontese. Prima [-terza] parte.” Internet Archive, 2 March 2018. https://archive.org/details/BIUSante_pharma_res018694/m ode/2up. Accessed 2 December 2024

Martins, Julia. “The Secrets.” Cems KCL Blog, 14 July 2023. https://kingsearlymodern.co.uk/ key-texts/the-secrets. Accessed 21 November 2024

Ruscelli, Girolamo. The Secrets of Alexis [Pseud.]: Containing Many Excellent Remedies against Divers Diseases, Wounds, and Other Accidents. With the Manner to Make Distillations, Parfumes … and Meltings … Newly corrected and Amended, and also Somewhat more enlarged in certaine places, Which wanted in the former editions., Printed by W. Stansby for R. Meighen, 1615. 1

“The Secrets of Alexis.” The Hospital vol. 16,407 (1894): 313.

- This is the citation for the edition of The Secrets I worked with based on the Dickinson College Library Catalogue, which, like many catalogues, accredits the book to Ruscelli.

In the “To the Reader,” Alessio1 talks about his knowledge of many languages and his “singular pleasure in philosophy, and in the secrets of Nature,” adding that he travelled the world for “seven and twenty years.” He gathered his “secrets” from other learned men, noble men, “poor women, artifacers, pesants, and all sorts of men.” When Alessio was “fourscore and two year and seven months” he met a sick man, suffering from an inability to urinate. Out of his “vain glory” and fears that the physician might use his “secrets” for selfish purposes, Alessio refused share the “secrets,” and the physician, fearing others knowing he sought outside help, refused to allow Alessio to administer the medicine himself. When the man passed, Alessio was overcome with guilt, saying that he “desired to die” because he was a “murderer” for withholding his “secrets.” To help alleviate some of this guilt, he was “determined to communicate” his recipes to the public, hence this book. He assures his readers of his trustworthiness by way of his age, this story, and the promise that the recipes are “true and experimented.”

In the “To the Reader,” Alessio1 talks about his knowledge of many languages and his “singular pleasure in philosophy, and in the secrets of Nature,” adding that he travelled the world for “seven and twenty years.” He gathered his “secrets” from other learned men, noble men, “poor women, artifacers, pesants, and all sorts of men.” When Alessio was “fourscore and two year and seven months” he met a sick man, suffering from an inability to urinate. Out of his “vain glory” and fears that the physician might use his “secrets” for selfish purposes, Alessio refused share the “secrets,” and the physician, fearing others knowing he sought outside help, refused to allow Alessio to administer the medicine himself. When the man passed, Alessio was overcome with guilt, saying that he “desired to die” because he was a “murderer” for withholding his “secrets.” To help alleviate some of this guilt, he was “determined to communicate” his recipes to the public, hence this book. He assures his readers of his trustworthiness by way of his age, this story, and the promise that the recipes are “true and experimented.” I couldn’t find much on Richard Androse, one of The Secrets’ translators, but I had more luck with the other, William Ward [Warde]. Ward (1534-1609) was a physician and translator and studied at Eton College and King’s College, Cambridge (Bayne & Wallis). He served as physician for both Queen Elizabeth I and King James I (Ibid.). He also translated several works from French to English, including The Secrets (Ibid.). It is likely from his expertise as a physician that he added recipes to the English edition as he translated it (Martins).

I couldn’t find much on Richard Androse, one of The Secrets’ translators, but I had more luck with the other, William Ward [Warde]. Ward (1534-1609) was a physician and translator and studied at Eton College and King’s College, Cambridge (Bayne & Wallis). He served as physician for both Queen Elizabeth I and King James I (Ibid.). He also translated several works from French to English, including The Secrets (Ibid.). It is likely from his expertise as a physician that he added recipes to the English edition as he translated it (Martins).

William Stansby (1572 – 1638) printed this edition in London at Cross Keys printing house. He apprenticed there under John Windet from 1589 to 1597 and then continued working with him, becoming co-partner in 1609, just before Windet’s death in 1610 (Bland). Windet focused on long print runs of small godly books, but after his passing, Stansby worked on smaller print runs of larger works and introduced more variety to the material than Windet had (Ibid.). During this period, he printed works by “John Donne, Sir Walter Ralegh, William Camden, John Selden, Michael Drayton, [and] Sir Francis Bacon,” (Ibid.) and, most famously, Ben Jonson’s first folio in 1616 (Wienberg). Stansby frequently printed banned or frowned-upon materials and was even arrested in the early 1620s for a pamphlet on Ferdinand II succeeding to the crown of Bohemia (Bland). Despite the change in focus, Stansby continued to use Windet’s printer’s device as seen on the section title pages of The Secrets (Windet). Around 1624, Stansby calmed down substantially, printing longer runs of psalms once more (Bland).

William Stansby (1572 – 1638) printed this edition in London at Cross Keys printing house. He apprenticed there under John Windet from 1589 to 1597 and then continued working with him, becoming co-partner in 1609, just before Windet’s death in 1610 (Bland). Windet focused on long print runs of small godly books, but after his passing, Stansby worked on smaller print runs of larger works and introduced more variety to the material than Windet had (Ibid.). During this period, he printed works by “John Donne, Sir Walter Ralegh, William Camden, John Selden, Michael Drayton, [and] Sir Francis Bacon,” (Ibid.) and, most famously, Ben Jonson’s first folio in 1616 (Wienberg). Stansby frequently printed banned or frowned-upon materials and was even arrested in the early 1620s for a pamphlet on Ferdinand II succeeding to the crown of Bohemia (Bland). Despite the change in focus, Stansby continued to use Windet’s printer’s device as seen on the section title pages of The Secrets (Windet). Around 1624, Stansby calmed down substantially, printing longer runs of psalms once more (Bland).