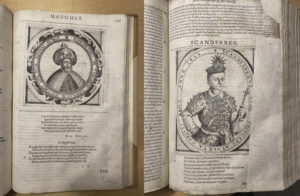

Richard Knolles’ The Generall Historie of the Turkes has enjoyed a long afterlife. Since its first publication in 1603 later scholars republished and updated the book, and it gained the respect of notable writers. The copy which now resides in the archives of Dickinson College, a first edition, bears witness to this four-century long history. While the provenance of this copy only becomes clear from the mid-twentieth century, the book carries several marks of this past–seemingly having been subject to many repair jobs.

From the moment it of publication in 1603, The Generall Historie became an instant classic. The book, being the first major English work tackling the history of the Turks, garnered an appreciation for Knolles’ ability to create a narrative from different sources (Woodhead 2004). This regard can be seen by the fact that The Generall Historie got republished in six editions in its first century of existence (Woodhead 2004). These were not mere reprints either; other authors such as Edward Grimeston extended the narrative to the year of their publications using diplomatic dispatches, even after Knolles’ death Woodhead 2004). That subsequent scholars felt the need to regularly update the history marks it as something special.

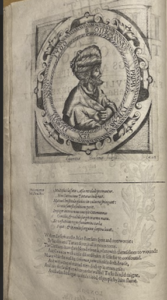

Scholars endured in their appreciation for the work. Writing in The Rambler no. 122 over a century after Knolles wrote his book, writer and critic Samuel Johnson praised him as the best historian England ever had, and that The Generall Historie in particular, “displayed all the excellencies that narration can admit” (Johnson 1751). The book’s influence does not stop there; Its fans included Lord Byron, and scholars believe it influenced even the writing of Knolles’ contemporary, Shakespeare (Bingham 2017). All this is to say that, centuries after first being put into print, The Generall Historie became immensely popular and shaped the English world’s perception of the Ottoman Empire and of History writing.

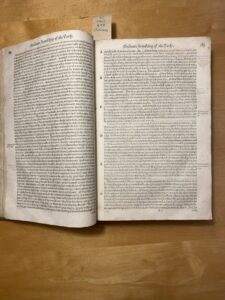

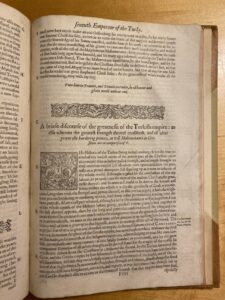

Figure 1: the beginning of the Discourse section

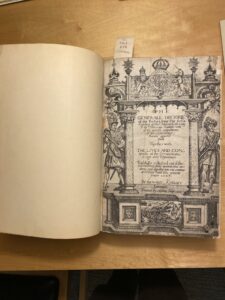

One question that that emerged during my research is over the book’s last section, titled “A briefe discourse of the greatnesse of the Turkish empire.” According to the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Knolles added this section starting with the second edition, making its presence in a first edition striking (Woodhead 2004). It of course could have been added after the fact–it starts at the beginning of a gathering, according to the signature mark–but that the page also contains the end of the proper narrative bugged me (figure 1). Surely the placement would not so neatly align between editions, and the discourse would start on a separate page. As an amateur I could not discern if this section got added afterwards by physically examining it, so comparing it to other copies became my best bet. I found a digitized first edition on Google books, and it matched Dickinson’s copy exactly, and a digitized 1631 edition on the Internet Archive has the same discourse on its own page after a continuation of Knolles’ narrative. It is certainly possible that two copies could have been altered the same way, but I believe this is doubtful. More work must be done to know for sure. Two possible scenarios include the title page simply wrong, or that the ODNB’s claim is incorrect.

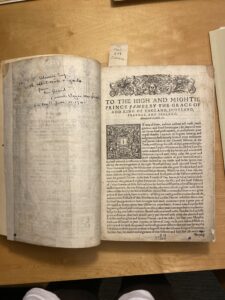

Figure 2: various marks and doodles picked up over the centuries

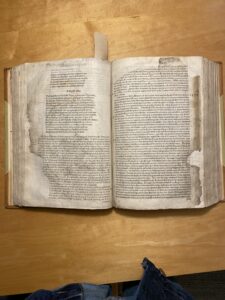

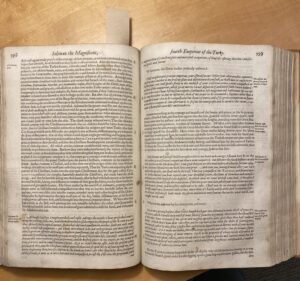

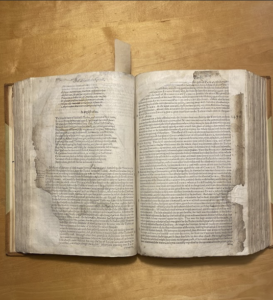

Besides this possible addition, the only marks from the first few centuries of the book’s life are scant doodles and the wear of time (figure 2). More recently, however, the book has seen quite substantial repair work. Certain pages have extensive decay; large chunks of paper missing and their edges frayed. In these areas, someone has added a backing of a thin sheet of perhaps rice paper to stabilize the damage (figure 3).

Figure 3: An example of extremely worn pages with repairs

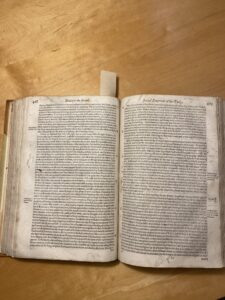

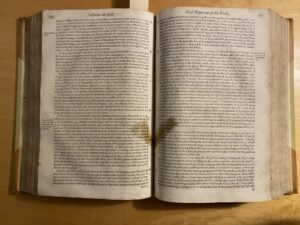

There have also been missteps. On page 534 and 535, another person appears to have placed several pieces of tape, the adhesive leaving massive brown stains on the pages (figure 4). It is unknown when work occurred, but they certainly wanted to preserve this copy.

Figure 4: Tape and stains from the adhesive

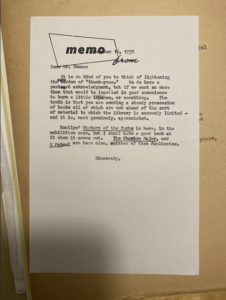

During the early 1940s Dickinson’s copy finally surfaces in the historical record. At some point, this copy came into the possession of Francis Wayne McVeagh. According to an inscription on the reverse of the title page, he gifted the book to his friend T. Edward Munce on June 13, 1941. An alumnus of Dickinson College (class of ’39), he sent the book to the institution in 1958 according to a memo, where it has resided ever since

Figure 5: Memo that dates when The Generall Historie came to Dickinson

(figure 5). This paper trail may give insight into another of the book’s mysteries: when it got rebound. The current binding is not original; the endpapers are of a much different stock, and the title on the spine has the modern spelling for starters. This begs the question of when this rebinding took place? A clue might be that MacVeagh’s message to Munce is written on the title page. Why not on write this on the blank endpapers instead of the centuries old paper? Munce wrote his name on the endpapers at some point, so why not MacVeagh? A possible solution could be that the rebinding occurred when MacVeagh or Munce owned the book. MacVeagh could not have written on the endpapers because they did not exist. This theory is, admittedly, a stretch. The work required to definitively prove this one way or the other is beyond my ability, requiring someone properly trained in book conservation and history.

The Generall Historie of the Turkes has been enjoyed by countless readers over the centuries. As an important work of history, its value has been recognized by several of those readers. As a work of history, it serves as a testament to that discipline’s early beginnings. The quality of Knolles’ narration impressed many critics over the centuries like Samuel Johnson. The care put into its restoration by a mystery book conservator who repaired this copy’s pages proves many people have recognized the immense value in its pages. The Generall Historie of the Turkes has had quite the afterlife indeed.

Works Cited

Bingham, Jonathan. “On Jon’s Desk: The Generall Historie of the Turkes, a beautiful book

linking the past with the present.” The University of Utah, 27 Mar. 2017, https://openbook.lib.utah.edu/tag/the-generall-historie-of-the-turkes/.

“Generall Historie of the Turkes First Edition – Richard Knolles.” Bauman Rare Books

Knolles, Richard. The Generall Historie of the Turkes. Adam Islip, 1603.

Knolles, Richard. The Generall Historie of the Turkes. Adam Islip, 1603. Google Books.

https://books.google.com/books/about/The_generall_historie_of_the_Turkes.html?id=BudbAAAAcAAJ.

Knolles, Richard. The Generall Historie of the Turkes. Adam Islip, 1603. Internet Archive, 2

Mar. 2021, https://archive.org/details/dli.ministry.02270/page/n805/mode/2up.

“The Rambler.: [pt.4].” In the digital collection Eighteenth Century Collections Online.

University of Michigan Library Digital Collections. https://name.umdl.umich.edu/004772607.0001.004.

Woodhead, Christine. “Knolles, Richard.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford

University Press, 2004. https://www.oxforddnb.com/display/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128- e-15752?rskey=i063hN&result=1#odnb-9780198614128-e-15752-div1-d1770859e286.