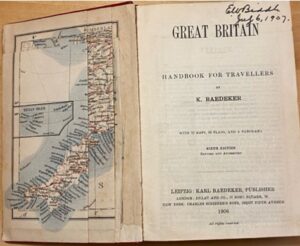

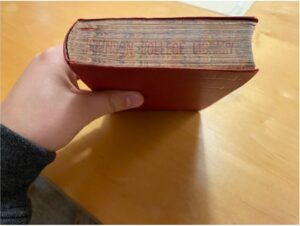

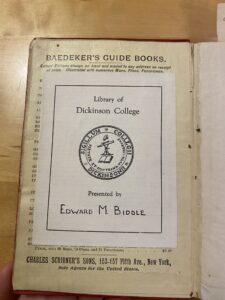

There are two inscriptions in Baedeker’s Great Britain. One reads, “EM Biddle, July 6, 1907.” The other, “Aug 1956 EM Biddle – Gift.” The library sticker behind the front cover of the Baedeker reads, “Presented by Edward M. Biddle.”

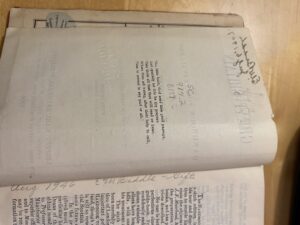

However, a closer look on the first inscription casts some doubt. Is that “M” really an M, or is it actually a “W”? The other Ms are clearly distinguished from the other letters. Could this mean that the original owner of this Baedeker’s was a different Biddle than the one who gifted it to the Dickinson Archives?

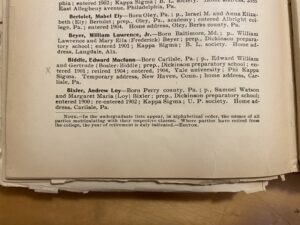

To try and find answers, I asked the archivists for some help in tracking down the possible Biddles. We found a file on one Edward Macfunn Biddle. It included an entry for him in the Dickinson Alumni catalogue; apparently, he was at Dickinson from 1901-1904, after which he attended Yale. There is also a list of Biddle alumni at the college, which included no less than three E.M. Biddles, and one E.W. Biddle.

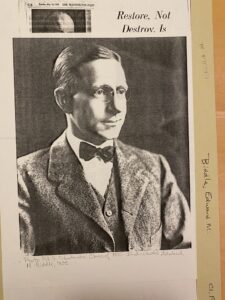

There is also an article on Edward M. Biddle in the file, written for The Dickinson Alumnus. According to this excerpt, his father was E.W. Biddle, a Judge and former president of the Dickinson Board of Trustees. Edward M. became a legal adviser and was an active member of his community. The most important part of this excerpt reads: “As a traveler he has been in Europe a number of times, has visited South America, as well as extended regions of the United States.” This of course indicates a possible use or ownership of this Baedeker’s guidebook, a fact exacerbated by its publication in 1906, soon after his graduation from Yale. This largely eliminates the possibility of the first

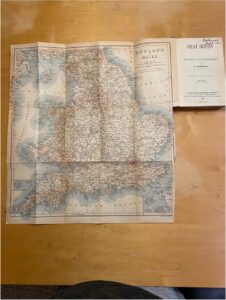

There is also an article on Edward M. Biddle in the file, written for The Dickinson Alumnus. According to this excerpt, his father was E.W. Biddle, a Judge and former president of the Dickinson Board of Trustees. Edward M. became a legal adviser and was an active member of his community. The most important part of this excerpt reads: “As a traveler he has been in Europe a number of times, has visited South America, as well as extended regions of the United States.” This of course indicates a possible use or ownership of this Baedeker’s guidebook, a fact exacerbated by its publication in 1906, soon after his graduation from Yale. This largely eliminates the possibility of the first  inscription in the guidebook being “E.W. Biddle” as opposed to the initially-assumed “E.M. Biddle”… except that E.W. was alive until 1931, when he died unexpectedly at 79. According to the Dickinson College Archives, E.W. was practicing law until 1895, at which point he became the president judge in the Cumberland County Court of Common Pleas. I have already noted the condition of my copy of Baedeker’s Great Britain – it has no annotations or inscriptions within it beyond the two at the beginning of the book, and there is very little wear beyond aging. The only clear indication of use is the broken bookmark, which could be because of age but also because of repetitive use. It is entirely possible to consider that E.W. purchased this book as a way to experience some form of travel from the comfort of his home. He also could have purchased the book as a gift for his son E.M. for graduating from Yale, which he did in 1906, and we know that he travelled. Uncertainty abounds.

inscription in the guidebook being “E.W. Biddle” as opposed to the initially-assumed “E.M. Biddle”… except that E.W. was alive until 1931, when he died unexpectedly at 79. According to the Dickinson College Archives, E.W. was practicing law until 1895, at which point he became the president judge in the Cumberland County Court of Common Pleas. I have already noted the condition of my copy of Baedeker’s Great Britain – it has no annotations or inscriptions within it beyond the two at the beginning of the book, and there is very little wear beyond aging. The only clear indication of use is the broken bookmark, which could be because of age but also because of repetitive use. It is entirely possible to consider that E.W. purchased this book as a way to experience some form of travel from the comfort of his home. He also could have purchased the book as a gift for his son E.M. for graduating from Yale, which he did in 1906, and we know that he travelled. Uncertainty abounds.

The other two Biddles in the directory, both ambiguously labelled only “Biddle, Edward M.” could be ruled out, as they graduated from Dickinson in 1886 and 1852; but they might have purchased the guidebook as another form of stationary travel. Although this Baedeker’s was donated by the E.M. Biddle who graduated in 1904, the Biddle family legacy is present enough in Dickinson college that E.M. could have inherited this book from another family member and then just donated it to the archives.

Because E.M. donated this Baedeker to the archives, I thought that it might be useful to see what other books he might have donated. If these books were also travel books or possessed handwriting that could distinguish the handwriting in the initial inscription of this book, it could help in getting a concrete answer about who owned and read this book. I was able to concretely discover three other books, one of which is Baedeker’s Berlin guidebook, a book about the U.S. Senate called Sketches of Debate in the First Senate of the United States, in 1789-90-91 by William Maclay, and another called The Book of the Homeless by Edith Wharton. This could indicate his ownership over the guidebooks, but we are in the same dilemma as when we started: were these previously owned by a different Biddle?

I also found that in the same year E.M. donated these books to the college, Dickinson purchased the “Biddle House,” which is now used by the Registrar’s Office and the Career Center. This generates some questions – why sell the house but not the books? Perhaps because the Biddle family was moving away; perhaps they needed some money but couldn’t be bothered to as for money over books. The mystery of the “E. Biddle” written in this book is tentatively solved, but unless one could find the receipt of purchase for this Baedeker’s the ambiguity lives on.

Works Cited:

Dickinson College Archives on Edward W. Biddle

https://archives.dickinson.edu/people/edward-w-biddle-1852-1931

Dickinson College Archives on Edward M. Biddle

https://archives.dickinson.edu/image-archive/edward-macfunn-biddle-1933

Dickinson College Archives on the Biddle House

https://archives.dickinson.edu/image-archive/biddle-house-c1900