Fig. 1 Edwin E. Willoughby, courtesy of the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation

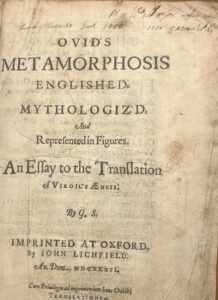

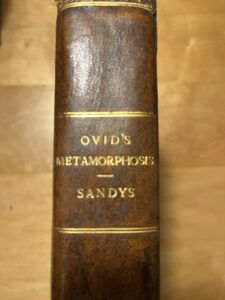

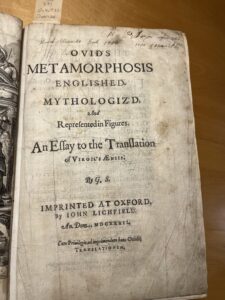

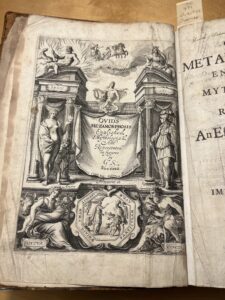

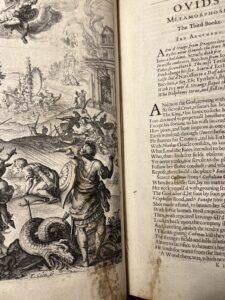

Since John Lichfield first printed George Sandys’ Ovid’s Metamorphoses Englished, Mythologiz’d, and Represented in Figures in 1632, the copy held within the Dickinson College Archives & Special Collections has travelled across oceans, finding its way to the United States at some unknown time after its publication in Oxford. As a travel writer who spent time in the Virginia colonies in the 1620s, Sandys may have had hopes that his work would make its way to the Americas, but he likely never imagined it would end up at a small liberal arts college in Pennsylvania after being owned by an alumnus who happened to be the Chief Bibliographer of the Folger Shakespeare Library.

Based on the book’s front matter, Sandys envisioned an elite, well-read audience for his work. With both a dedication and panegyric addressed to King Charles I and an address to Queen Henrietta Maria, Sandys positioned his work as worthy of the very top of English society. As a translation of a classic work, with countless other references to different myths peppered throughout, the book also assumes a learned audience with some degree of knowledge of the classics. It is unlikely that anyone without prior knowledge of Ovid and his works would be inclined to pick up Sandys’ translation. Readers would not be familiar with the text itself unless they were familiar with Metamorphosis and its myths, whether that be in Latin or in English.

Fig. 2 The bookplate bearing Dr. Willoughby’s name.

In regards to education level, Ovid’s Metamorphoses Englished, Mythologiz’d, and Represented in Figures reached its intended audience in its last owner, Edwin E. Willoughby, before arriving at Dickinson College. The history of this book’s ownership in England is unknown; the name “Thomas Chadwick” appears on the title page alongside the year 1780, but this inscription does not indicate where Mr. Chadwick lived. He could have been from England, or he could have lived in the American colonies amidst the American Revolutionary War. As there is no information on him, we likely will never know. But we know for certain that this copy must have been in the United States by October of 1959, when Edwin E. Willoughby passed away with Ovid’s Metamorphoses in his possession. Dr. Willoughby was the Chief Bibliographer of the Folger Shakespeare Library from 1935-1958 and focused his scholarship on the print history of Shakespeare’s work and the history of the King James Bible (“Edwin Eliott Willoughby (1899-1959) | Dickinson College”). The bookplate pasted into the cover of Ovid’s Metamorphoses identifies this particular book as part of the gift Dr. Willoughby’s sister, Dr. Frances Willoughby, made to Dickinson in memory of her brother (See Figure 2).

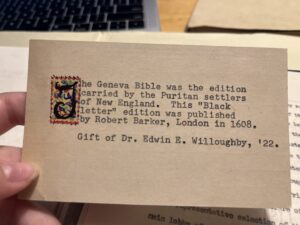

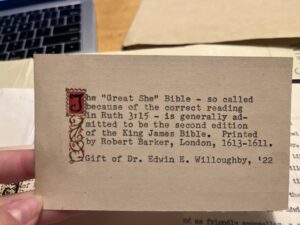

During his career, Dr. Willoughby acquired many rare books for his own personal collection and sent a number to the library at his alma mater, Dickinson College. In their file on Dr. Willoughby, the Archives possesses multiple memos from college librarians thanking Dr. Willoughby for gifting copies of various works. On one occasion, while working as the Chief Bibliographer at the Folger Shakespeare Library, he gifted the college a 1608 “Black letter” edition of the Geneva Bible and c. 1611-1613 copy of the “Great She” Bible (See Figures 3 and 4). The large gift Frances Willoughby made in honor of her brother in 1960 was the last in a long series of philanthropic donations started by Dr. Willoughby himself decades prior.

Fig. 3 The notecard recording Dr. Willoughby’s gift of a Geneva Bible.

Fig. 4 The notecard recording Dr. Willoughby’s gift of a “Great She” Bible

Notably, there are no records of Frances Willoughby donating this particular edition, the 1632 Ovid’s Metamorphoses Englished, Mythologiz’d, and Represented in Figures, in any of Dickinson’s archival records. There are a few documents that mention Ovid’s Metamorphoses by name as part of the Willoughby gift, but they all designate it as the 1626 edition (See Figure 5). The Dickinson College Archives & Special Collections does not own the 1626 edition of Sandys’ translation, which I confirmed by checking the catalog of the archives’ physical holdings. This left me with two possible explanations to this discrepancy; one was that at some point Dickinson did own a 1626 edition, and that acquisition was highlighted in the documentation, but was excised from the archives in the years since. The alternative is that either Dr. Frances Willoughby or the librarians cataloging the gift mistook this 1632 edition of the text for the 1626 edition and recorded it incorrectly. I consulted with our archivists, Jim Gerencser and Malinda Triller-Doran, and the three of us were in agreement that the latter explanation was far more likely. Had a 1626 edition of Sandys’ Ovid’s Metamorphoses been excised, it would have been under Jim’s direction, and he explained that he would have never gotten rid of a rare book that was part of the Willoughby collection.

Fig. 5 Document mentioning Sandys’ 1626 translation of Ovid’s Metamorphoses as part of the collection donated to the Dickinson College Library in 1960.

Jim’s insight meant that a copy of the 1626 edition likely never existed in the Dickinson College Archives, so at some point in the donation and cataloging process, someone made an error. Had it been simply the wrong year that was recorded, one might not dwell too long on it, as human error is common and there were no computers in 1960 to keep the streamlined catalogs that the archives have today. But it was more than just the year—all archival documents record the full information for the 1626 edition, which include the publisher and location of publication (William Stansby, London) and the complete title, Ovid’s Metamorphoses English’d. John Lichfield published the 1632 edition in Oxford and it had a much longer title which signified its status as an illustrated translation. Furthermore, this information is all located on the title page of the text. One would only have to open the book to realize that the copy in the archives’ possession was the 1632 illustrated edition, not Sandys’ 1626 translation. I cannot account for this mistake, nor can Jim and Malinda, but it demonstrates the incredible responsibility book collectors, conservationists, archivists, and librarians have when it comes to the texts they preside over. Making mistakes is human, and easy, but misrecorded information can also affect the work and research of future students and scholars. Fortunately, the online catalog correctly lists the 1632 edition as the version that Dickinson College holds in the archives.

Works Cited

“Edwin Eliott Willoughby (1899-1959) | Dickinson College.” Dickinson.edu, 2019, archives.dickinson.edu/people/edwin-eliott-willoughby-1899-1959. Accessed 1 Dec. 2024.

Gerencser, Jim and Malinda Triller-Doran. Personal Interview. 2 December 2024.