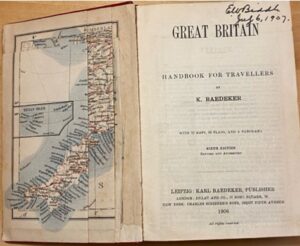

Researching the afterlife of Baedeker’s Great Britain introduced me to an entire subsection of the book collecting world I had previously been unaware of. My intention was to try and track what I am calling the Edition Evolution of the Great Britain Guide, as my copy is the sixth edition, and given the scope of my guidebook (the table of contents spans several pages, and as I mentioned in my previous post, it covers content from geographic locations, floor plans, and popular activities within its area), it is not unreasonable to assume that there would be at least some form of significant change between editions. Luckily for me, I was not disappointed.

In my research, I was able to find out some of the history behind the legacy of Karl Baedeker, spanning several generations of Baedeker, and their guidebooks. Karl was born in 1801, into a family of bookseller and publishers. He started the “Baedeker” business in 1827, which coincidentally was around the time when tourism was really taking off (pun unintended). Following the foundation of this business, his first guidebook was published in 1832, 74 years before the publication of my own guidebook. The first edition was titled Rheinreise von Mainz bis Koln, as the Baedeker family was German – the first English edition guidebook wouldn’t be printed until 1861. This edition was called Baedeker’s Rhine, the first edition of which is currently being sold for a little over $5,000. As his company built its reputation, Karl travelled everywhere he could to gather the information to construct his guidebooks, until his death in 1859. He is hailed as the inventor of the formal guidebook according to at least a few people, including a chapter in a book titled Giants of Tourism by D.M. Bruce, R.W. Butler, and R. Russell, where they refer to him as “the perceived ‘inventor’ of the formal guidebook,” and his guidebooks themselves as a “bible” for 19th-century travelers. After Karl’s demise, his three sons continued his business, and it is still operating to this day.

As I gathered this information, I came across a wide variety of Baedeker’s guidebooks that are being sold online. First editions go for quite a bit of money, especially on rare book seller’s websites. But they are also being sold on places like Etsy, eBay, Amazon, and generally a good number of used bookselling platforms. Even when I narrowed my search down to just the Great Britain guide, there are still a lot of results. This surprised me – given the condition of my book, which implies that it was largely used a shelf piece or perhaps escapism on behalf of the owner, I had assumed that these books were pretty exclusively “collector” edition books. But the original intention of the books was for them to be actively used as convenient travel guides, so of course they were widely spread for tourism purposes. I also came across a lovely book called the Baedekeriana (2010) by Michael Wild, who was fascinated by the history of the Baedekers and wanted to compile it. It includes written accounts from people who worked with the Baedekers, and is an anthology of articles about past Baedeker guidebooks.

The Baedekeriana details the intense attention to detail and accuracy, as well as the impact that cultural differences and World War I and World War II had on the printing of guidebooks, especially for a German-based company. I am excited to spend more time understanding this history myself, but for now I turned my attention more avidly towards the specific evolution of the Great Britain guidebook. Initially, I was only able to find the editions that bookended my own – the 5th edition, printed in 1901, and the 7th printed in 1910. Given that my own book was printed in 1906, these dates only affirmed to me that the attention to detail referenced in my research on the Baedekers was accurate.

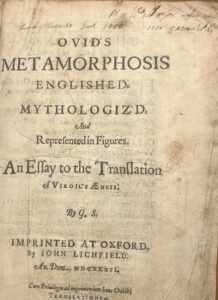

Fig. 1

My edition of the guidebook is described as having “22 maps, 58 plans, and a panorama” (Fig. 1). The 5th has “18 maps, 39 plans, and a panorama”; the 7th “28 maps, 65 plans, and a panorama.” The visible growth of content just in the frontmatter of each book is a testament to the attention to detail given to the content of each guidebook. Over just 9 years there is an increase of 10 maps in just one specific guidebook. How are other books growing? How did this specific guide change along with significant world events?

I was able to find an 1894 Baedeker’s Great Britain on eBay that showed some of the internal book – it has “16 maps, 30 plans, and a panorama.” Interestingly, the title page says it has 16 maps, but the list of Baedeker’s guide books behind the front cover lists the third edition of Great Britain as having 15 maps. I’m not sure why this discrepancy exists, and after taking a closer look at the other PDFs I found, the 5th edition describes the Great Britain guide book in that same list to have “16 maps, 30 plans, and a panorama”, the 7th doesn’t display that list at all, and mine is frustratingly obscured by a library identification card.

Something else I stumbled across while I was traipsing across the internet trying to find other editions of the Great Britain guide was the shocking discovery of just the Baedeker maps being sold. The very things that drew me in initially are apparently the main draw for a good number of interested parties. On Etsy some of them are being sold for $115, which is an unfortunate loss for those looking to find intact editions.

Works Referenced:

Wild, Michael. Baedekeriana: An Anthology. Red Scar Press, 2010.