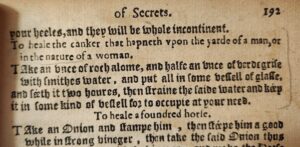

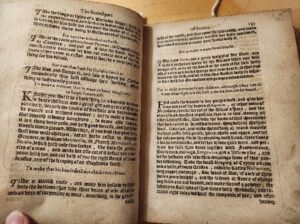

As I established in my last blog post, the physical construction of The Historie of Fovre-Footed Beasts and The Historie of Serpents shows clear signs of frequent use—and occasional abuse—by past readers. A rebinding and damage ranging from scratched-out illustrations to ripped-out pages, abundant marginalia, and scribbling suggests that, while the book was well-consulted, as Topsell hoped, it was not always well-treated (Figures 1, 2, & 3).

Figure 2

Figure 1

There is abundant evidence of a readership for Beastes, but I can deduce little else; uncovering who these folks might have been has proven to be a difficult calculus. It was my initial hope that by working my way backward from the most recent owner of this book, I could perhaps find one of its first. Beastes once belonged to Edwin E. Willoughby, Dickinson alumnus, former Chief Bibliographer of the Folger Shakespeare Library, and scholar of early printed Shakespeare works and the King James Bible. After his death in 1959, his sister and executor, Col. Frances Willoughby, coordinated with the College archivist and librarian Charles Sellers to donate Beastes along with Edwin’s dizzying collection of over four hundred rare books; it was his wish that future students—like myself—could learn about bibliography through these books. And what a gift. I only wish Beastes and the Willoughby files accompanied accession documents, bills of sale, receipts, anything, as without them, I cannot trace ownership past the Willoughbys—alas, a dead end. (I have reached out to the Folger Shakespeare Library to see if, by chance, they possess any pertinent documentation which is unlikely. I have not yet heard back. Hopefully, they do. I can use whatever they find to establish this book’s ‘afterlife’ in my next and final blog post).

Figure 3

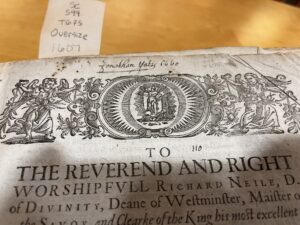

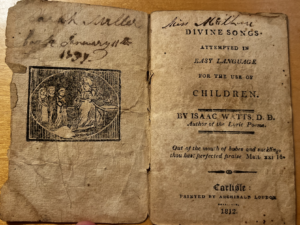

In working on the previous blog post, I did discover a reader who inscribed his name in ink in the front matter: a “Johnathan Yates,” signed 1660 (Figure 5). If he is the same as the one found in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, ‘John Yates’ (c. 1586–1660) was an Anglican clergyman, theologian, and physician (“John Yates,” 2004)(Sprunger, 697-698). He was admitted as a sizar to Emmanuel College, Cambridge, in 1604, matriculating the same year, and earned his B.A. in 1607/08, M.A. in 1611, and B.D. in 1618, and was a fellow of the college from 1611 to 1616. Yates was ordained deacon and priest in September 1614 and later served as a preacher at St. Andrew’s, Norwich, from 1616 to 1622. In 1622, he became rector of Stiffkey, Norfolk, where he remained until his death in 1660. I cannot determine definitively that the present John Yates is the same who inscribed his name in Beastes, as the accompanying date—1660—is the year he died, and ‘John,’ though an abbreviated form of ‘Johnathan,’ is not necessarily the same name. Notwithstanding my inability to corroborate his relationship to this book, John Yates might yet serve as a point of departure from which to hypothesize the likely reader of Beastes.

Yates was by all accounts a learned and notable controversialist: as an author, he wrote many theological works; he also had a license to practice medicine in 1629, presumably issued by the Royal College of Physicians—I cannot, however, determine the capacity in which he exercised this license for we know so little about his local ministry (“John Yates,” 2004). If this Yates is indeed the same individual, his position as a clergyman and scholar would suggest that he was part of the audience Topsell hoped to reach with Beastes: the “learned men” of England. As an educated man no doubt with interests in intellectual stimulation and spiritual edification, Yates would have been drawn to Topsell’s bestiary, especially given its theological overtones. More generally, Yates’ interests in “practical theology” would have aligned well with Topsell’s conception of natural philosophy, which often connected the study of animals to both spiritual and medical concerns (Springer, 702, 704-706).

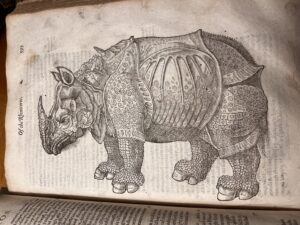

Yates likely would have been interested in the systematic approach that Topsell and Gesner both advocated. However, contrasting the ‘notes to readers’ in Beastes with the ‘note to readers’ in Serpents provides more clues about the intended audience and their relationship with the author. Topsell’s objective with the publication of Beastes, as he states in “To The Learned Readers,” was not only to gather all that had been written of beasts into one “Dictionary” for the consultation of “learned men” in their vulgar tongue but also to show to his “countrymen” the moral instruction God provides in all animals. To achieve this goal, Topsell, somewhere between tribute and theft, lifted his text and woodcuts almost wholesale from Conrad Gesner’s Historiae Animalium, including a famous broadside of “The Rhinoceros”––a woodcut which Gesner himself ‘borrowed’ from Albrecht Dürer (Kusukawa, 311) (Figure 4). Topsell was indeed an assiduous compiler but a profoundly unoriginal man.

Figure 5

Figure 4

Topsell recognizes that a compilation as ambitious as his must yield to a certain tentativeness; it is better, he believes, to publish an incomplete treatise than to let it languish unprinted in the potentiality of his untimely death. Therefore, he appeals to readers to contribute insights, add information, or correct mistakes. And his readers did just that: since Topsell published The Historie of Fovre-Footed Beastes in 1607 and The Historie of Serpents in 1608, one—or several—of the proprietors bound them to create a more complete reference book (when they did this, however, I cannot determine). Topsell responded in kind to his readers: in the “To The Reader” preface to Serpents, Topsell acknowledges the many protestations he received from the readers of Beastes because of the typographical mistakes therein; Serpents, he assures readers, features no such errors.

This dynamic between Topsell and his readers reveals something about the intellectual context in which audiences received Beastes. Readers like Yates, whoever they may have been (scholars, clergymen, aspirant zoologists––we may never know definitively), were far from passive consumers of Beastes and Serpents: they actively engaged the text, provided feedback, pointed out errors, inscribed their names, marked passages for later use, and even altered its material form through rebinding. While we cannot identify the readers of Beastes, they were as instrumental in shaping it as Topsell himself. Indeed, this book was not a static receptacle for animal lore but a dynamic, material space where reader and author cooperated—at times, competed—to articulate and cultivate knowledge.

WORKS CITED

Kusukawa, S. (2010, July). The sources of Gessner’s pictures for the Historia animalium. Annals of Science. 67 (3): 303–328. http://www.rhinoresourcecenter.com/pdf_files/128/1286404337.pdf. Accessed 5 Dec. 2024.

Sprunger, Keith L. “John Yates of Norfolk: The Radical Puritan Preacher as Ramist Philosopher.” Journal of the History of Ideas, vol. 37, no. 4, 1976, pp. 697–706.

“John Yates.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004, https://www.oxforddnb.com/display/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-30193?rskey=Aup4DQ&result=1. Accessed 5 Dec. 2024.

WORKS CONSULTED

Carpo, Mario. Architecture in the Age of Printing: Orality, Writing, Typography, and Printed Images in the History of Architectural Theory (2001 translation), p. 110.

Heltzel, Virgil B. “Some New Light on Edward Topsell.” Huntington Library Quarterly 1, no. 2 (1938): 199–202.

Isaac, S. (2018, March 16). The familiar and the fantastic: The Historie of Foure-Footed beastes by Edward Topsell, 1607. Royal College of Surgeons. https://www.rcseng.ac.uk/library-and-publications/library/blog/the-familiar-and-the-fantastic/. Accessed 5 Dec. 2024.

Lancaster, James A.T. “Natural Knowledge as a Propaedeutic to Self-Betterment: Francis Bacon and the Transformation of Natural History.” Early Science and Medicine 17, no. 1/2 (2012): 181–96.

Lewis, G. “Topsell, Edward (bap. 1572, d. 1625), Church of England clergyman and author.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. 23 Sep. 2004; Accessed 1 Nov. 2024.

Ong, Walter. “Writing Restructures Consciousness: The New World of Autonomous Discourse” in Orality and Literacy: 30th Anniversary Ed. Milton Park OX: Routledge, 2014. 77–114.

University of Washington. University Libraries. “The Historie of Serpents.” Edward Topsell, 1608. https://www.lib.washington.edu/preservation/preservation-services/conservation/topsell. Accessed 5 Dec. 2024.

Westhrop, H. (2007, March). Edward Topsell, The History of Four-footed Beasts and Serpents, 1658. Special Collections featured item for March 2006 by Helen Westhrop, Rare Books Library Assistant. University of Reading. https://collections.reading.ac.uk/special-collections/wp-content/uploads/sites/5/2020/01/Featured-Item_Topsell_compressed.pdf. Accessed 5 Dec. 2024.

Printed by Archibald Loudon in 1812,

Printed by Archibald Loudon in 1812,