During our class cultural artifact activity, I couldn’t decide what manga to bring, but I knew I wanted to bring a manga. (Manga read right to left)

I considered bringing The Whole of Humanity has Gone Yuri Except for me, (yuri is the japanese term for girls love) a book I picked up at barnes and noble because of it’s insane title. It turned out to be a somewhat camp, utterly insane, supernatural tale of a girl waking up and realizing that every single person in the world had been transformed into a lesbian woman.

I considered Bloom Into You, written by Nio Nakatani. I own every copy of this manga, and it’s super dear to my heart. This story features Yuu and Touko. Touko is outspokenly in love with – and wants to kiss – Yuu, and is fine if Yuu doesn’t reciprocate. Yuu is overwhelmed by this pressure, and feels like their relationship will lead nowhere, not because she isn’t attracted to girls, but because she’s not really sexually attracted to anyone, and never has been. She’s felt isolated from her peers her whole life, in this regard, atleast, and the story is about both of them coming to really love eachother and grow mutually as people.

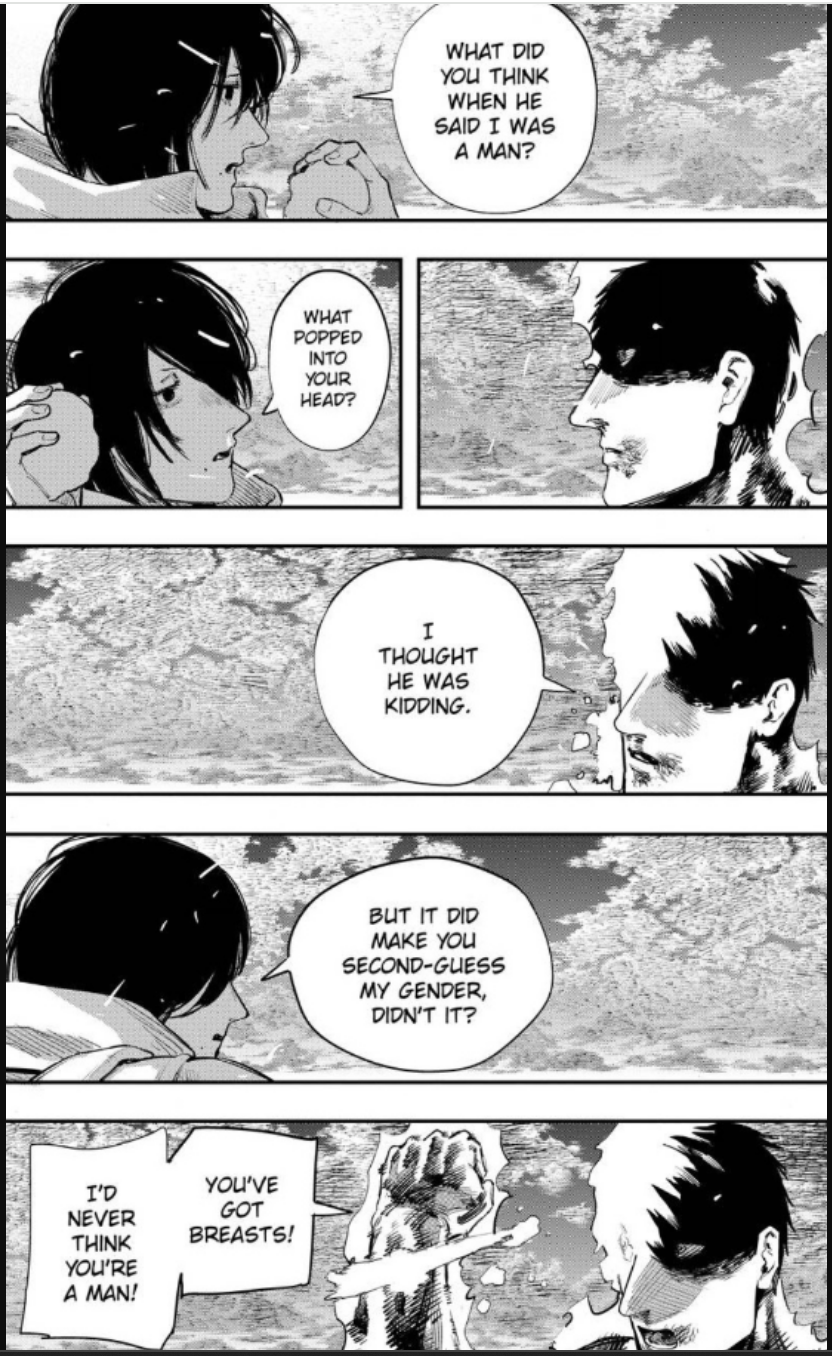

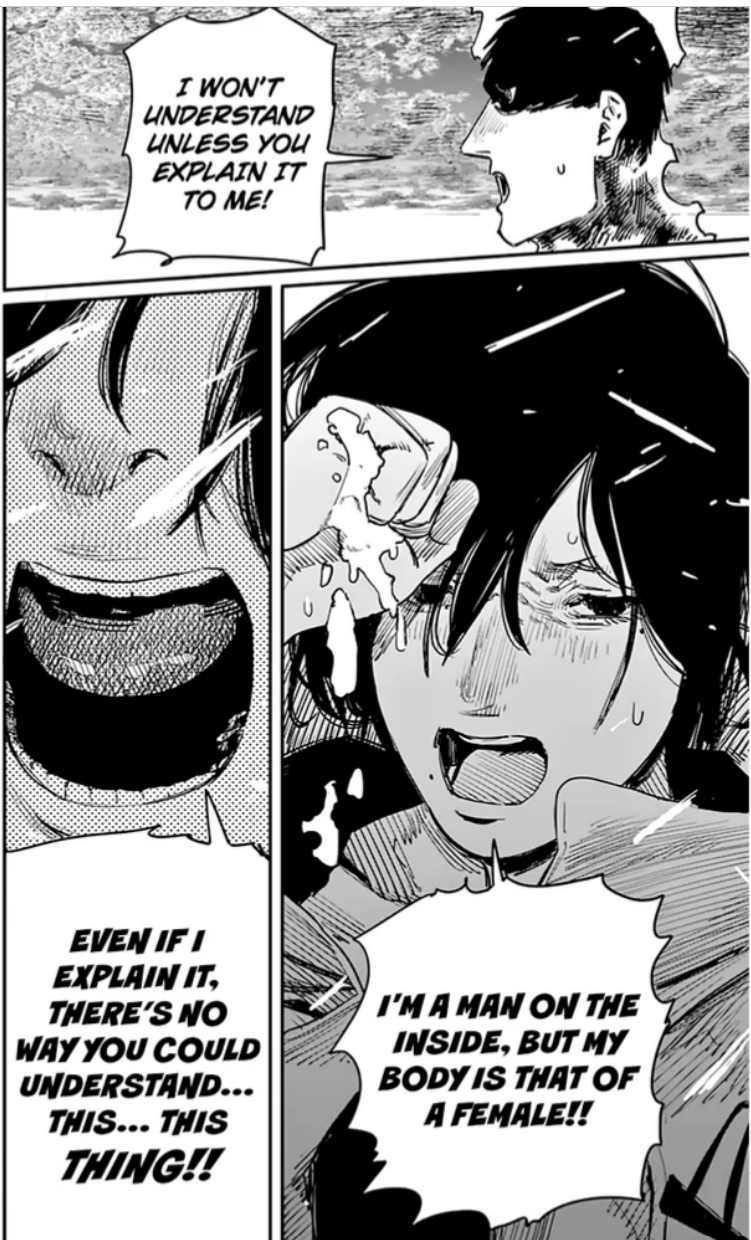

I even considered Fire Punch, written by Tatsuki Fujimoto. This work is very graphic and surreal in terms of themes and violence. The main character grows up in a dystopian wasteland, where few are cursed with and exploited for their supernatural regenerative properties. He is set on fire, early on, with flames that never go out, and since he cannot die, he walks the land a perpetual human torch. I almost chose Fire Punch, not for him, but for one of his companions that joins him on his journey. Togata is the deutragonist, who is rare in manga because he makes explicitly clear his gender dysphoria. Togata has a woman’s body, but confesses to Agni (the human torch) that he is a “man” on the inside. What makes Togata so tragic, is that he is also cursed with regeneration. Every time he dies (a constant device throughout the story) he must return to a body that he considers himself trapped in. A feminine body. Also related to our class is Togata’s role in the story. Togata is a self proclaimed director, and he orchestrates several events (and films them) throughout the story. It makes me think of diving into the wreck, returning to that dystopian land with a camera. But this time, Agni is the flashlight that Togata is using to explore the wreckage. (the following panels are not exactly page x and page y, there may be one sequence in between.)

The manga I actually chose is How do we Relationship? By Tamifull. Like Bloom Into You, this is a super well known yuri manga in the community. How do we Relationship? is unique because the story starts when the two characters start dating. Most stories have the whole “will they/won’t they” through line, and while that does come into play because they break up once (or twice) having them meet and get together in the first chapter really sells the vibe that no, this is going to be a realistic portrayal of two people that love eachother, struggling to treat themselves right, struggling to treat eachother right, and struggling with the dynamics of a relationship. The character development is treated so well in this story, and I love how modern and well handled it feels. The characters, Miwa and Saeko, are openly lesbian, Saeko has a heterosexual friend that literally calls her on the phone while she’s having sex with a dude. They live actual lives, they have actual pasts, and the way Tamifull handles things like “visibility” is really nice. This manga feels super genuine to me, and I loved seeing Miwa and Saeko care for eachother. Misunderstandings feel believable and in character, not phoned in, you root for their growth and good communication, and you’re eventually rewarded. I think something powerful that How do we Relationship? touches on, is interconnectedness. While Miwa and Saeko are lesbian, and that’s a big part of their story, it’s not “how do lesbians relationship” it’s “how do we” and while that’s cheesy, I truly think anyone can learn and appreciate this story.

There isn’t a great “so what” here, I just wanted to talk about manga.