The Adirondacks

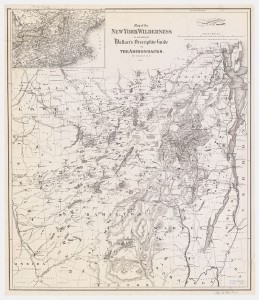

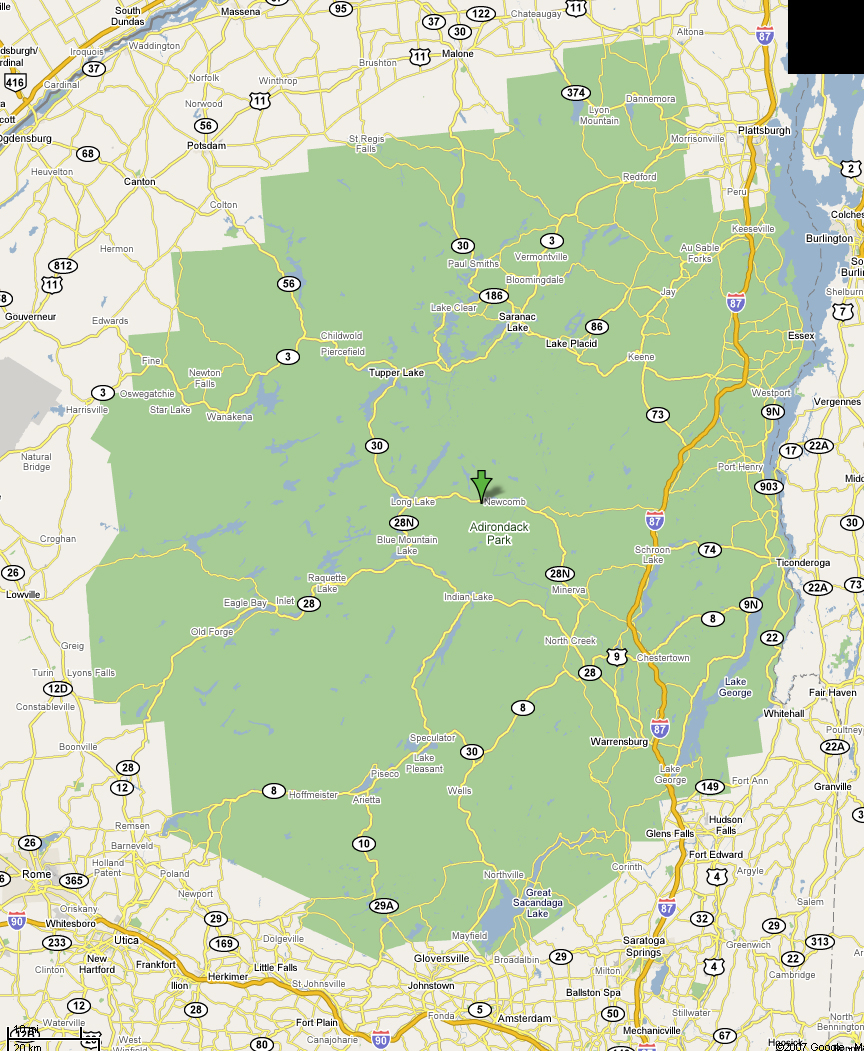

In his 1995/2007 book, Hope Human and Wild, Bill McKibben argues the the Adirondacks are one of only three (3) places on our planet that have established a balance between the human and the nonhuman worlds within a single “developed” and humanized space (the other two are Kerala, India and Curitiba (Cur-i-chee-ba), Brazil. This mountainous region in the northern New York has among the strictest federal, state, and local controls over land use, building codes, and zoning anywhere in the United States. Along with Curitiba and Kerala, the Adirondacks–according to McKibben–represent humanity’s best efforts yet to find ways to live in harmony with their nonhuman surroundings, to balance the natural and the urban, the wild and the cultural, into a unity of projected goals that protect the wild and the tame, the raw and the cooked (as Levi-Strauss once said). This has been accomplished through public, private, and partnership commitments to preserving the natural wild environment, while at the same time making the Adirondacks welcoming to all people who share this vision. Nevertheless, as Pete Nelson has recently noted, there are current debates over wild lands in which “Sides are taken with dizzying speed, as those who think we have too much wilderness in the Adirondacks face off against those who think we need more.” The area of over six (6) million acres–larger than America’s five smallest states–is the largest “park” in the Lower 48 States. It covers a combined land mass of almost 19,000 square miles, over 48,000 square kilometers. Glacier, Yosemite, the Great Smoky Mountains, Yellowstone and the Grand Canyon National Parks could all be dropped down inside the Adirondacks–a state park–with space to spare. Here is an 1876 map from Wallace’s Descriptive Guide:

followed by a modern map (click on either one to enlarge for details). In recent years the Adirondacks have experienced ongoing discussions about growth and expansion of the human population. Towns like Lake Placid (the location of the 1932 and 1980 Olympics and childhood home of Abolitionist John Brown), Saranac Lake (site of a famous tuberculosis sanatorium in the early years of the 20th century), and Lake George (recreational lake and mountain playground for thousands of New Yorkers over the decades) are scattered across this vast area of wilderness and protected land and, since the 1960s and 70s, the pressures of urban and recreational activity have increasingly led to new laws, increased regulation, and sometimes acrimonious debates about the future of the Park. On one side are those who argue that it is the pristine, untouched natural elements of the Adirondacks that makes them so special in the first place, on the other side are those who note that it has only been the economic viability of these lands –vast areas having been logged over by commercial interests by the middle of the nineteenth century: fir and spruce to make paper, hemlocks for tanning, hardwood species for the charcoal industry, and the entire woodlands for commercial lumber and firewood. As early as 1874, Verplanck Colvin argued, in one of his regular reports to the New York State Legislature, that “Unless the region be preserved essentially in its present wilderness condition, the ruthless burning and destruction of the forest will slowly, year after year, creep onward [ . . . ] and vast areas of naked rock, arid sand and gravel will alone remain to receive the bounty of the clouds, unable to retain it” (History). By the end of that century, the legislature had taken three major steps toward the creation of the Adirondack Park as we now know it: 1885 (the establishment of the Forest Preserve), 1892 (The Adirondack Park itself with stronger protections than the original preserve), and 1895 (the addition of the crucial “Forever Wild” principle, which still governs a large percentage–2.6 million out of 6.5 million acres–of the Park today). Any changes to “Forever Wild” principle (no changes of any kind without the consent of the people) demand the consent of back-to-back state legislatures and a referendum supported by a majority of New York’s voters.

As a vacation retreat, the Adirondacks benefitted greatly–like all of the Northeast–from the widespread acceptance of air conditioning in the 1970s and 80s. Families that might have once travelled or moved to the northern U. S. stayed in, moved to, or vacationed in Virginia, the Carolinas, and Florida. Great Camps like Sagamore, Santoni, and Topridge gave way to one to ten-acre lots on which middle-class families could build their “Small” camps and summer escapes. Towns with 200 inhabitants now swell to 2,000 in the summer, and the winter landscape is punctuated only by loggers and the occasional winter hunter or back-county hiker. In addition, a number of large resorts serve increasing numbers of resort-seekers and convention-goers. In the summer, sea planes drop fishing and hunting parties deep in the wilderness acres, without roads, formal campgrounds, or any modern services. According to historians, even indigenous Indians in this part of North America did not live in the Adirondacks; they only passed through the region in hunting and food gathering parties, partly because of the harsh winters and partly because of the rugged terrain.

View from the top of Whiteface, a 4,865-foot mountain in the HIgh Peaks region. It is a world class ski-slope, located not far from the Adirondack’s highest peak, Mount Marcy (5,344 ft. or 1,628 m.). On a clear day, it is possible to see the tall skyscrapers of Montreal and across the state of Vermont into the White Mountains of New Hampshire. In purely geological terms, these mountain are growing faster than the Himalayas: the “‘Dacks,” as they are locally known, are increasing in altitude at a rate of approximately one foot every century, not quite one inch every ten years.