For anyone interested, Loreena McKennitt (famous folk singer and musician) adapted The Lady of Shalott to music. She’s also adapted and drawn inspiration from other famous literary works including The Highwayman (my personal favorite), Dante’s Inferno, and works by Yeats, Shakespeare, and Sir Walter Scott.

Author: Bluestocking

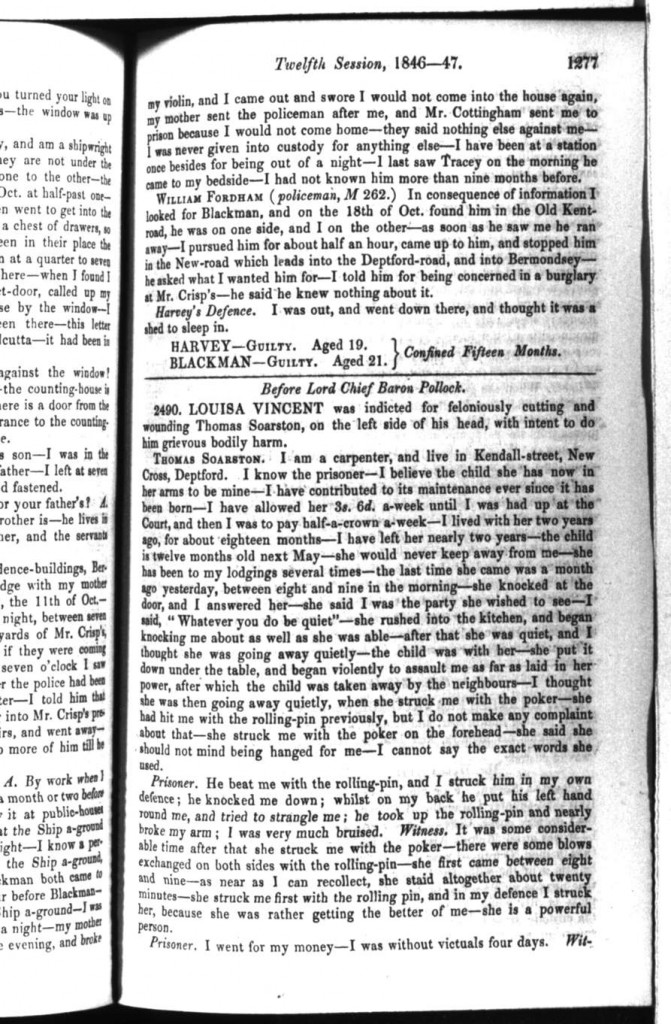

Archive Project: “LOUISA VINCENT, Breaking Peace Wounding, 25th October 1847”

Nothing beats a good, old fashioned, Victorian sex scandal. This court case from the Old Bailey follows the testimony of Louisa Vincent, a woman on trial for attacking her former lover and father of her illegitimate child. The proceedings include testimony from both the defendant and her alleged victim.

I chose this text for my Victorian Queer Archive project because it includes so many details that would scandalize, yet intrigue, a Victorian audience. The subject matter is taboo and serves to queer assumptions about Victorian society’s prudishness and aversion to sex, especially given the public nature of trials in the 19th century in London. Furthermore, the “queer” nature of the subjects–poor, criminal, sexual, unmarried–highlights that the figures that inhabit the edges of Victorian society (and who receive public attention) are not always the pure, innocent, and gentlemanly ideal.

In his text “Sex, Scandal, and the Novel”, William A. Cohen suggests that sex scandals publicly reveal sexual information and knowledge that might otherwise be best kept secret. The lewd sensationalism of crime and passion can be seen in this transcription. For example, Louisa Vincent (Prisoner) and Thomas Soarston (Witness/victim) both argue over who initiated the fight. Soarston accuses Louisa of attacking him first, while Louisa accused him of not providing for their child and of starving her (“I was without victuals four days”). The “he said/she said” nature of the testimony is something that is seen in contemporary sex scandals as well. Curiously, Louisa is on trial despite evidence that Soarston also hit her. I would suggest that this is because Louisa is obviously an outcast from Victorian society: the presence of an illegitimate child marks her as impure and tainted. In addition, the implication that she is a prostitute (and Soarston her pimp) further alienates her from polite Victorian society. On the other hand, illegitimate children and infidelity in general were tolerated more for men, therefor Soarston’s breaches of Victorian norms do not reflect as poorly upon him.

Cohen also mentions that the “unspeakability” of the sex scandal which actually serves to create discourses that reinforce the notion of sex as taboo. Instead of the sex scandal quashing discussions of forbidden sex, it actually creates the opposite effect. For instance, trials at the Old Bailey were a form of public entertainment. These trials, however, still made use of heavily coded language in order to avoid transgressing too heavily. This is evidenced in the italicized explanation of the testimony:

“The prisoner put in a written defence, stating that the prosecutor, after premissing her marriage, had induced her to live with him, telling her that his wife was transported; that after some time he wished her to obtain money by prostitution, which she refusing he deserted her, agreeing to allow her something for the child; that she went to him for the money, when he knocked her down and ill-used her, and all she did was in her own defence.”

In this excerpt alone, there is mention of forced prostitution, infidelity/polygamy, and even of rape (“he knocked her down and ill-used her”). None of these transgressions are openly named, instead this excerpt employs language that Cohen calls the “richly ambiguous, subtly coded, prolix and polyvalent” that is inherent in the sex scandal.

Finally, while “scandal teaches punitive lessons”, indicating its moralizing nature, sex scandals still incite in a Victorian audience the possibility of transgressing and the potential for the queer to enthrall and thrill.

Works Cited

Cohen, William A. “Sex, Scandal, and the Novel.” Sex, Scandal, and the Novel. Victorian Web, n.d. Web. 10 Nov. 2016.

http://vqa.dickinson.edu/shortstory/louisa-vincent-breaking-peace-wounding-25th-october-1847

LOUISA VINCENT, Breaking Peace Wounding, 25th October 1847. London’s Central Criminal Court. 25 Oct. 1847. The Proceedings of the Old Bailey Online. Web. 10 Nov. 2016.

Save

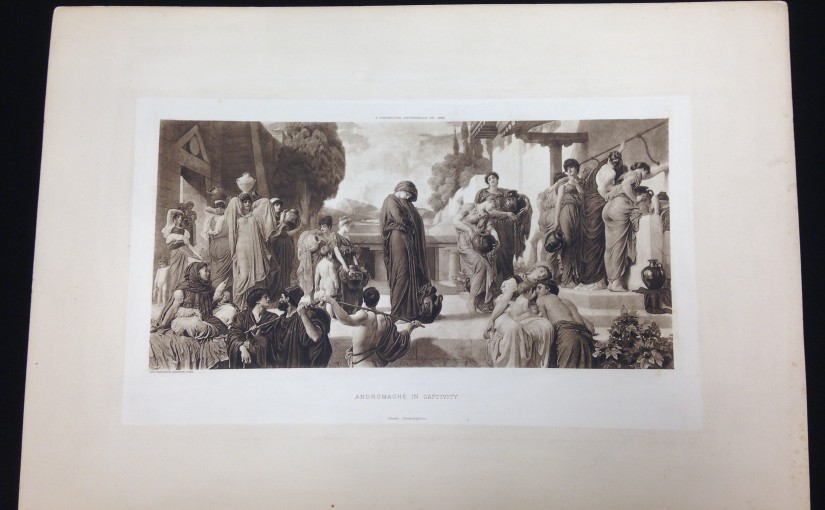

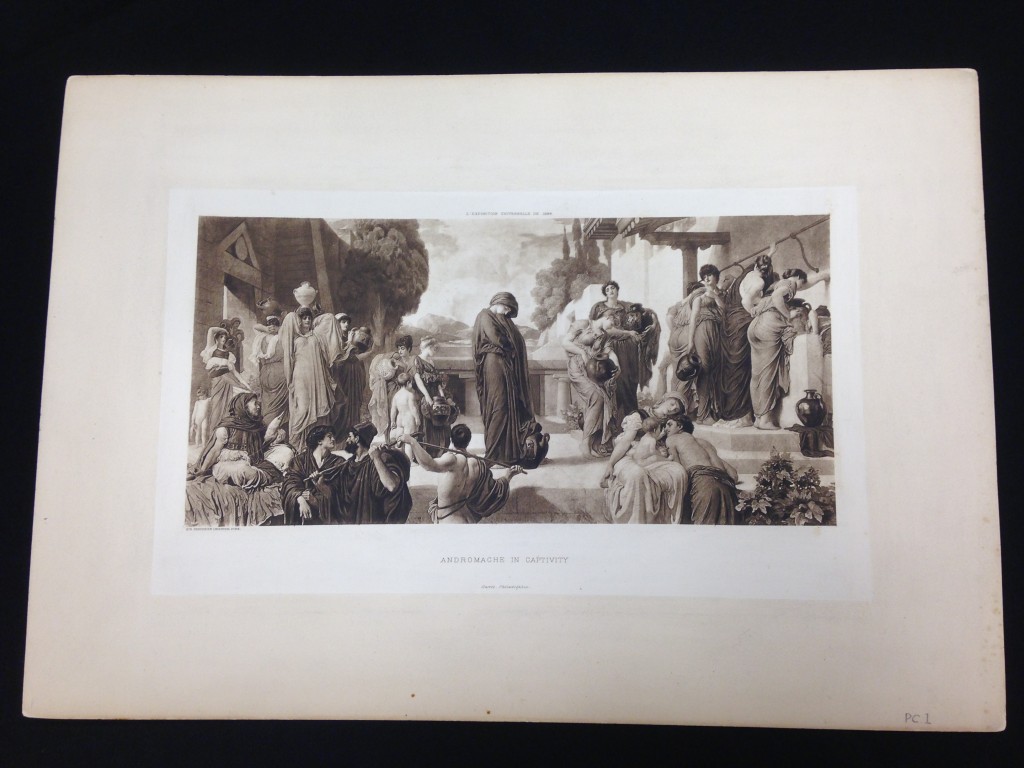

Andromache + Propaganda

This piece– “Andromache in Captivity”–is a reference to the character Andromache from Greek mythology. After Troy fell to the Greeks, Neoptolemus forcibly takes Andromache as his concubine, enslaves her brother, and murders her child. This image depicts Andromache in the aftermath of the Trojan War, when she is living as a captive in a foreign land.

In the image, Andromache’s suffering at the hands of her captor is being used as a propaganda tool. In colored versions of the art piece, Andromache’s skin is quite pale, in contrast to the darker olive and brown tones of the people in the street. Additionally, she is dressed in black clothing (which for Victorians signified deep mourning) in contrast with the bright robes of her captors. Andromache is mourning the loss of her home, her family, and likely her freedom (or purity, perhaps), while her captors celebrate and debauch themselves in the streets.

Furthermore, Andromache has been painted as the Western victim of a decadent and savage society. Notice that the other people in the image show lots of skin (some are even nude), while Andromache is covered head to foot. By subtly contrasting color of textiles and fullness of cover, the painter implies that Andromache is pure while her captors (and their women) are less civilized and more savage. When looking at the painting, it becomes clear that many of the figures, especially the women, appear to be watching Andromache. Their stares indicate that Andromache is merely an object or a spectacle, underscoring her lack of agency and utter powerlessness.

Additionally, fears that European women would be kidnapped and raped by foreign men played a large role in the justification and the proliferation of colonialism. Artwork such as this fuels the notion that foreign cultures (here, the Greeks) pose a danger to white, Western women and ought to be treated as a threat. Of course, this justification of colonialism is ironic, because colonizers posed a significant danger to foreign women. Indeed, fears of foreign men raping white women were weaponized by colonizers to justify the colonial mission, which often included raping foreign women with impunity. Analyzing images, such as Andromache in Captivity, illuminate the ways in which colonialism was represented and justified in art and culture, and can be helpful in understanding the role of art in shaping and circulating the (narrow) view of foreign cultures.

The Beguiling of Men

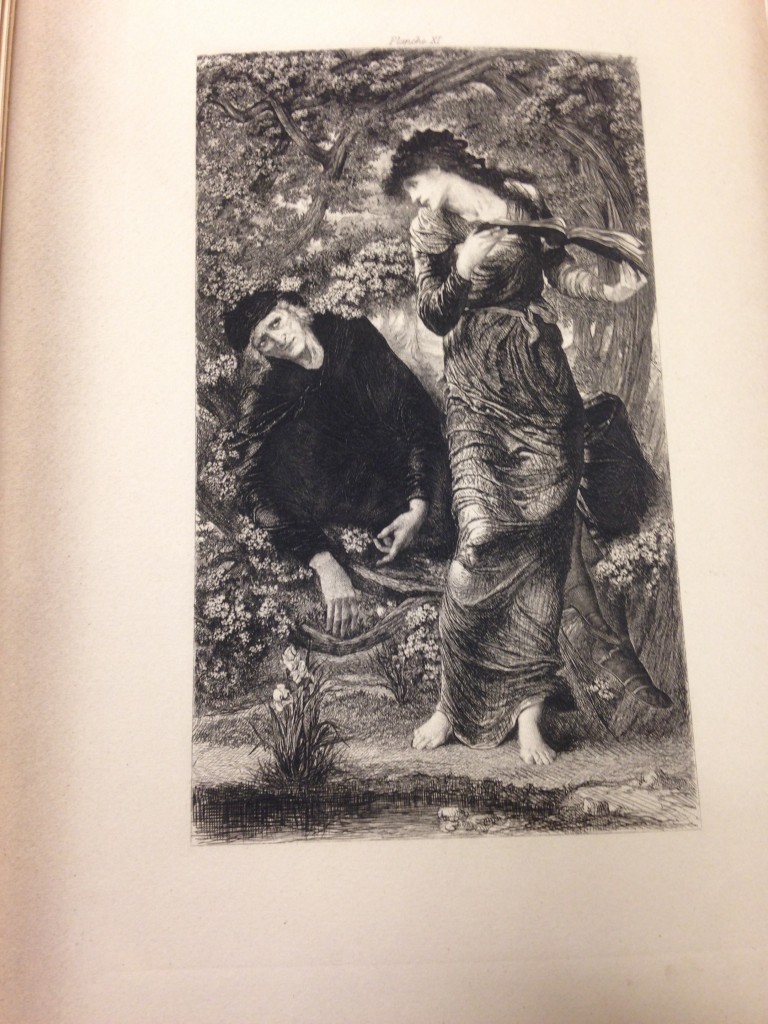

Adolphe Lalauze’s painting the “Beguiling of Merlin” depicts a woman named Nimue reading from a book of spells and seducing Merlin.[1] This image is highly reminsicent of the poem “La Belle Dame sans Merci: A Ballad” because they both feature a male figure being bewitched by a beautiful, mysterious woman. In both case, the woman in question—a femme fatale—seems supernatural in nature (in the Keats poem, she may be a faery or a changeling and in the Lalauze painting she reads spells that send Merlin into a trance.[2]

The Victorian web describes the femme fatale as a mixture of “sensual, erotic but invulnerable” traits, making her alluring, dangerous, but also demure enough to avoid suspicion.[3] In the Keats poem, for example, the woman in the meads cries during their lovemaking, implying that she pretends to be an virgin (the visions the knight experiences of other duped men implies she has seduced many men before him, thus negating her virginity).[4] In the painting, Nimue exposes her neck, a disarming move that demonstrates her vulnerability. However, it also indicates her erotic power over the man she seduces. The neck is an erogenous zone, therefor the sexual overtones of this action should not be underestimated.

Furthermore, parity between the poem and painting can be seen in the shared setting. In both instances, the femme fatale has bewitched a man in the heather. The beautiful, flowering setting of the meads and later the grot obscures the darker undertones of the femme fatale narrative. The combination of lovely scenery and innocence of the lady allow her to seduce the man and entrap him forever.

“I met a lady in the meads,

Full beautiful—a faery’s child,

Her hair was long, her foot was light,

And her eyes were wild.”[5]

Even when the man may suspect something is amiss–as evidenced when he notices her alarmingly “wild eyes”–he still proceeds with sleeping with her.[6] The wild eyes allude to her true nature, a nature that is steeped in folklore and magic. Indeed, perhaps this is what makes her so attractive in the first place. Once again, the idea of a dangerous woman is tied directly to both the natural and the supernatural world. In this case, perhaps the knight overlooked her wild eyes due to other, less obviously dangerous, aspects of her character. Her long hair, her light footfalls, and her beauty make her irresistible. Nimue of the painting has likewise lulled Merlin into a state of bliss, to the point where he is no longer standing and instead is lounging among the flowers in the bushes.[7] The lazy angle placement of his arm and hand also indicate that he is in a trance and he seems unable to take his eyes off of Nimue. Interestingly, in the Arthurian legend, Nimue learns the bewitching spells from Merlin. By using both her beauty and her erotic magnetism, the femme fatale is able to use the man for her own gain.

[1] “The Beguiling of Merlin” ‘The Beguiling of Merlin’, Edward Burne-Jones. Lady Lever Art Gallery.

[2] “The Beguiling of Merlin”

[3] Lee, Elizabeth. “The Femme Fatale as Object.” The Victorian Web. Brown University, 1997.

[4] Keats, John. La Belle Dame Sans Merci. 1819.

[5] Keats, John.

[6] Keats, John.

[7] Burne-Jones, Edward. The Beguiling of Merlin. 1872-7. Oil on canvas. Trout Gallery, Carlisle PA.

Count Fosco, Femme Fatale

Like many character in the novel, I find myself attracted to and interested in Count Fosco in spite of myself. As the primary villain and an obvious creep, ordinarily I would turn my attention to other characters like Laura, Walter, or Marian. That being said, I keep returning to Count Fosco. I simply cannot help myself. Therein lies his power. His character is a true enigma: obviously wicked, but deliciously exciting and charismatic. Perhaps his most fascinating trait is his ability to use sexuality and sex as a means to achieve his desires. He uses the others’ attraction to him for his own ends, and is thus able to control and manipulate all of the other players in the narrative. His wife, for example, literally eats out of the palm of his hand (p. 222) and is complicit in his crimes. Sex becomes the force through which Fosco creates chaos. Marian also becomes a victim of count Fosco. She knows that he is dangerous, but still finds herself drawn to his charm and seduced by his charisma. Count Fosco operates as a femme fatale within the novel. He uses sexuality as a means of manipulation. He is an exception to most forms of literature, however, because he is male while most characters who weaponize sex are women. The traditional femme fatale is almost always young, gorgeous, dark, and sultry. Count Fosco, on the other hand, is rotund and old. His allure (and perhaps some of the distrust) can be traced back to the xenophobia surrounding his foreignness (he is an Italian). Like many femme fatales, he appears dark and mysterious, almost exotic in stark contrast to the more delicate female characters who populate the pages of the novel.

The scene where his femme fatale nature becomes most explicit is the moment where he writes in Marian’s journal after she has fallen ill. Like the femme fatale who triumphs after her prey has fallen asleep after sex, here too Marian is at her most vulnerable when she has been weakened (possibly poisoned) by Count Fosco.

“I breathe my wishes for her recovery. I condole her on the inevitable failure of every plan she has formed for her sister’s benefit.” (p. 336)

Here Fosco makes his wicked nature explicitly known, along with his mocking respect for his mark, Marian. Marian, like many a character before her, knows that Fosco (the femme fatale) is no good, yet takes the bait anyway. Fosco even seems to lament this in the postscipt he adds to her diary. On one hand, he claims wish for her “recovery”, yet as a possible cause (what really made her sick?) of her sickness, this passage reeks of irony. Even if his wish was sincere, the next statement, offering condolences on her failed plans, makes it clear that Fosco is glad to have bested her. Like many a great villian, Fosco cannot help but to gloat in his victory.

Dangerous Woman: Anne Catherick and the Guarding of Sexual Purity

Anne’s responses to moments of suspicion regarding her sexuality are representative of a trend within Victorian culture of women being held responsible for guarding and maintaining their sexual purity.

Within moments of her introduction, Anne assures Walter that her presence on the road late at night does not indicate a flawed moral character. The words that she chooses, such as “suspect” and “wrong”, imply that Anne feels guilty and recognizes that strangers will regard her with distrust (Collins, 25). The underlying subtext of this passage implies that Anne believes Walter suspects her of prostitution. Her readiness to disabuse Walter of this notion (a notion he does not suggest in the narration) speaks to the Victorian sensibility that women must always guard their purity. Additionally, it also suggests that women who transgress boundaries (as Anne is doing) must be especially careful to protect their reputations from censure. Despite her child-like demeanor, Anne seems aware that others interpret her sexuality as dangerous.

Later in the narrative, Walter considers Anne’s possible motives for penning the anonymous letter. He thinks that her “misfortune” may refer to sexual impropriety (Collins, 101). The words that Walter chooses such as “common” and “ruin”, both have sexual connotations. In the 18th century, for example, women who engaged in sex before marriage were considered “common” or vulgar (http://www.dictionary.com/browse/common?). Furthermore, Walter believes it is also typical (or common) for women to seek to destroy the relationships of the men who wronged them in love. “Ruin” is explicitly sexual, as it refers to a woman’s premarital loss of virginity and thus the destruction of marriageability and honor. Walter checks Anne’s expression for signs of shame that might indicate the nature of her misfortune (Collins, 101). This checking for guilt further indicates that this conversation is really about Walter suspecting Anne of improper sex. Anne understands the ramifications of Walter’s line of questioning, which compels Anne to re-affirm her purity. In response, she asks Walter “what other misfortune could there be” other than her Asylum confinement (Collins, 101). Her question reads as almost defiant, willing Walter to openly question her romantic history while also indicating to Walter–and the audience–that Anne is innocent. In spite of this, she still remains perplexed about the nature of Walter’s questions, as indicated by the “bewilderment of a child” that Walter attributes to her (Collins, 101). She knows enough about Victorian mores to deny sexual deviancy, however, she still appears to be ambivalent or oblivious about why Walter would suspect her of such wrongdoing. In this manner, she denies all suspicions of promiscuity.

Mrs. Fairlie is likely responsible for Anne’s implicit knowledge of Victorian moral sensibilities as well as responsible for her understanding sexual expectations. For instance, Mrs. Fairlie told Anne to dress in white because “little girls…look neater and better” and thus more innocent and pure (Collins, 61). If Anne is an illegitimate child (perhaps Mr. Fairlie’s), Mrs. Fairlie may have sought to purify Anne (a living reminder of Mr. Fairlie’s infidelity) by forcing her to wear only white. If, however, Anne is Mrs. Fairlie’s illegitimate child (and mention of Anne’s “mother” is merely a red herring), Mrs. Fairlie could have forced Anne to wear white as a means of correcting the impurity and sin she sees in herself and subsequently projects onto Anne. Mrs. Fairlie may never have explicitly instructed Anne to regard her purity with vigilance, but Anne could internalize Mrs. Fairlie’s obsession with whiteness and purity. As a result, Anne understands that she must always be attentive to how others view her sexuality while also being ready to affirm her innocence if brought into question.