cw: trauma, genetalia related-language

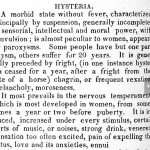

Hysteria, in an article from the New York Times in 1843, is defined by being, “a morbid state without fever, characterized principally by suspension, generally incomplete or sensorial, intellectual and moral power with convulsion; is almost peculiar to women, appears by paroxysms.”

This is a particularly confusing definition, especially because it is not a consistent one, a number of sources from the 19th century categorize hysteria as a catatonic state, like a severe depression, or as Freud or L. E Emerson would say psychosomatic illness brought on by a sexual trauma of some sort, while Charcot (another researcher of hysteria) deemed it hereditary and tried to treat it with hypnosis. The unifying idea of hysteria is that it is a woman’s disease, lying dormant in their bodies until it manifests in a nervous temperament, being overstimulated or feeling a sense of “ennui.”

It is also clear in these texts that “paroxysm” refers to a “female physical response” or orgasm, that is supposed to be the cure for hysteria. The idea that a “woman’s disease” can be cured by stimulation or therapeutic massage by a physician or midwife until orgasm definitely queers the idea of heteronormative sexuality. Hysteria is supposed to be cured through a consummate marriage, but because of the patriarchal notion of intercourse, most women would not reach “paroxysm” thus feeling unfulfilled. The cure for hysteria, a massage/stimulation of the vulva negates the idea that a fulfilling sexual experience revolves around the presence of a man with a penis.

Furthermore, the idea that the lack of orgasm is due to some sort of hereditary problem or psychosexual trauma is problematic, because it reinforces the idea that a woman must reach orgasm through vaginal penetration of a penis, leaving no room for any sex other than heterosexual sex.