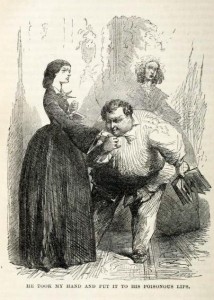

E. W. Fallerton’s etching Within the Lines Siege of Agra 1857 is more complex than it might initially seem. The figures are situated in a domestic space, enclosed in a house with a small window. Details suggest a rustic and “Eastern” setting: the bare walls; the Oriental rug; the large jars on the ground; the woman’s bare feet, her slippers lying beside her; and the woman’s draped clothing and head scarf, evocative of Indian or Middle Eastern fashion.

Even the woman’s skin tone and features are darker than the idealized European women depicted by many artists during the nineteenth century. She has dark hair, dark eyebrows, thick eyelashes, and a prominent nose. The baby’s white blanket, the central focus of the painting, emphasizes the darkness of the woman’s hands.

The title of the etching confirms this Eastern setting, as the “Siege of Agra” was a battle in India between Indian rebels and British colonialists [1]. This historical context problematizes Fallerton’s seemingly innocuous depiction of motherhood. The woman is depicted in a traditional “Mary, mother of Jesus” pose in Western art, with her eyes cast down toward the baby she holds in her arms.

Yet the baby she holds has white skin and light hair, as does the second child sleeping in the background. The etching thus suggests two possible narratives: the children are the result of “mixed” sexual relations with a British colonist; or, the children are not hers, and the Indian woman depicted is a nurse or servant. Both narratives problematize the notion of “natural” motherhood.

In his depiction of the Duchess in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, Lewis Carroll also interrogates domesticity and motherhood. The Duchess’s household, far from the nurturing environment depicted in Fallerton’s etching, is downright abusive. The cook throws frying pans at the pair, and the Duchess “toss[es] the baby violently up and down” as she sings a “lullaby” that advocates child abuse:

“Speak roughly to your little boy,

And beat him when he sneezes” (46).

The Duchess “flings” the “queer-shaped little creature” at Alice, a mere child herself, to take care of it (47). Alice demonstrates a maternal instinct to protect the child that the Duchess clearly lacks: “Wouldn’t it be murder to leave it behind?” (48). However, when the baby starts turning into a pig, Alice thinks “it would be quite absurd for her to carry it any further,” and she is “relieved” as she watches the pig “trot quietly into the wood” (48).

The baby’s metamorphosis into a pig is unnatural, as the adjectives “queer-shaped” and “absurd” suggest. The word “unnatural” here is useful, as it historically denotes illegitimacy (OED). Like the figure in the etching, Alice is not the natural mother of the baby; by the end of the scene, they are not even the same species. The unnatural pig-child can no longer occupy the domestic sphere, and so takes refuge in the wilderness or wood. Perhaps Carroll, like Fallerton, is making a veiled commentary on race, motherhood, and illicit sexuality.

1. “Indian Mutiny.” Encyclopaedia Britannica. Encyclopaedia Britannica Online Academic Edition. Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., 2015. Web. 22 Mar. 2015. <http://academic.eb.com/EBchecked/topic/285821/Indian-Mutiny>.