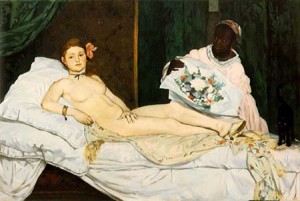

The femme fatale is beautiful and powerful—and constantly oppressed. She is viewed as dangerous and because of this is tamed in a variety of ways. As Laura Mulvey argues in her article “The Femme Fatale as an Object”, one of the many ways in which the femme fatale is weakened is through representation in art. She explains that the painted woman has been reduced to “a type of formula of rotund pieces of flesh, hair and facial features. They weren’t portraying individual women, but an idealized composite of recognizable parts”(citation). This argument comes to life in a handful of Victorian works, a good example being Manet’s famous “Olympia”.

This piece is one of many works of art that depict the woman as an object to gaze at and admire. Like Mulvey argues, she is not an individual but an idealized woman. Her tiny feet, daintily covered genital area, stylized breasts, and outward gaze are all details that turn our subject into an object of male pleasure as opposed to a powerful sexual figure. Although the powerful sexual woman in art is elusive, she does in fact exist. Moreau’s “The Apparition” is a perfect example of the unrestrained femme fatale.

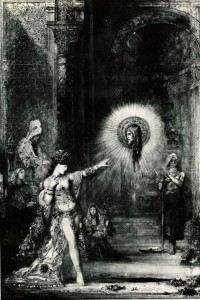

Unlike the vulnerable naked figure in the previous piece (and so many others), this woman is not vulnerable in the slightest. She is both naked and powerful—using her own sexuality to her advantage. This piece tells the story of Salome (the woman) who danced so beautifully and sensuously she was granted anything she desired, which happened to be the head of John the Baptist. Salome is sensuous, powerful, and quite obviously dangerous. She is the femme fatale unchecked.

Salome is the free femme fatale for two main reasons. First of all, she stands out. The entire painting focuses on her and her victim. In artworks that repress the femme fatale, the woman is objectified and stripped of her own identity. Salome’s possession of her own name is the possession of her own identity. She is not another woman to look at and gaze upon but a woman to revere. But you couldn’t gaze into her eyes even if you desired to. The objectified femme fatale cannot consent to give her gaze to others for it is always on display at the leisure of the man. But Salome is turned away, almost as if she is dismissing those trying to gaze upon her.

Salome is the reason why the femme fatale is oppressed, restricted and objectified. She wields the unchecked sexual power than men are so afraid of…and maybe this fear is for good reason. Who knows whose head she’ll want next.