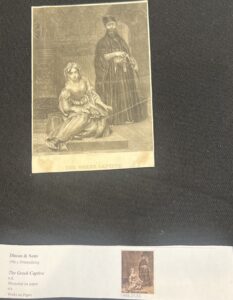

When observing the posture and body language in this artwork, the relationship between the man and the woman captures the viewer’s attention right away. The man, positioned further back in the composition, seems to exert control over the Greek woman, who is portrayed in a submissive, vulnerable position on the floor. The title of the piece suggests key aspects: that the woman is Greek and possibly held captive, underscoring themes of conquest, cultural superiority, and gender disparities. The man’s religious attire indicates that he is likely a high priest, and his stance and expression convey authority, alongside a palpable tension between him and the audience. His gesture towards a weapon hint at readiness for violence or force, presumably to protect the women depicted in the scene from any potential harm. The artist’s perspective creates a voyeuristic experience, as though we are witnessing a live moment.

The contrast between the sitting woman and the standing man highlights the gender hierarchy prevalent during the Victorian Era. This artwork embodies the male gaze, presenting the woman’s body as both exotic and an object of display, reflecting on how foreign women were portrayed in colonial and orientalist art. Relating this analysis to course materials, the piece address’s themes of perception, sensuality, fear, curiosity, and temptation. By engaging with gendered power structures and the Western interpretation of the Eastern world, it demonstrates how visual art can both create and reflect the cultural and historical contexts of domination and desire, such as the concepts of the Femme Fatale and the Angel in the House.

Moreover, both this artwork and Christina Rossetti’s poem, “In an Artist’s Studio,” position the woman as a vessel for meaning rather than a creator of her own narrative. Elements of fear, sensuality, temptation, and control surround her, yet her voice is notably absent. The shared tension in both works—evident in the woman’s posture and the poetic tone—highlights how the artistic gaze can contribute to both preserving and confining. Connecting the painting and the poem enhances our understanding and reveals a broader cultural trend of silencing and aestheticizing women under the guise of beauty, art, or devotion. Both pieces challenge us to rethink our perceptions and consider who has the power to define and present imagery.