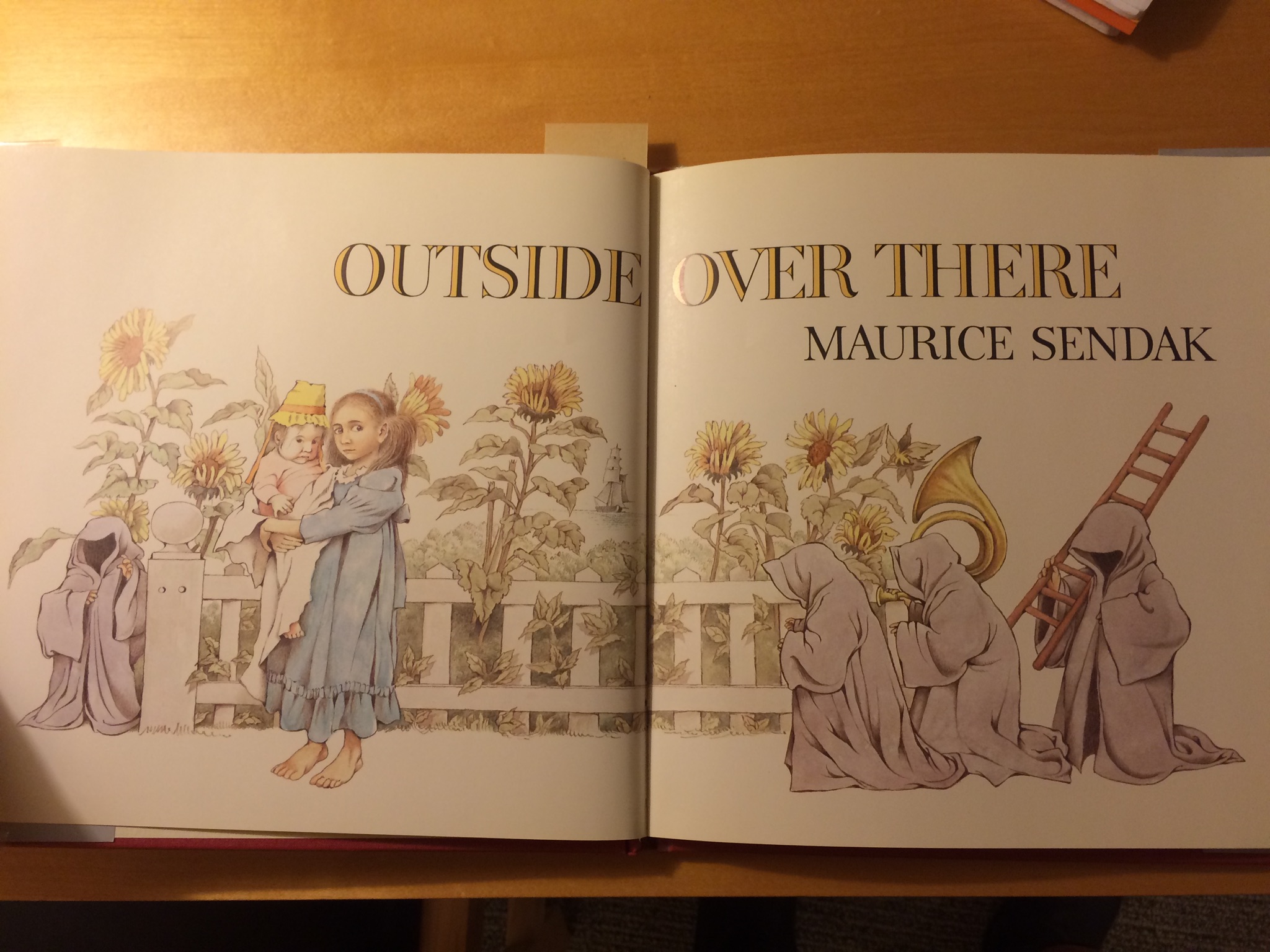

Maurice Sendak’s 1981 illustrated children’s book, Outside Over There, tells the story of a young girl named Ida who must rescue her baby sister from goblins who have kidnapped her in order to marry her off to one (or more) of their kind. The title page of Outside Over There alone picks up the themes of foreign anxiety, the otherworldly realm of sexual danger, gender divisions, and sisterly care—all of which we’ve discussed in the context of Christina Rossetti’s “Goblin Market.”

The title itself evokes the foreign world of the goblins: it is not only outside, while the girls often remain inside the house, but it is also over there, in a space not normally inhabited by the baby or by Ida (one is kidnapped and taken there, the other must “climb backwards out” of her window and fly around for some time to find it). The dangerous otherness of this world is emphasized by the goblins’ mysterious grey cloaks and hunched, low-to-the-ground posture, as well as the black, absent spaces where their faces should be. These features contrast greatly with the pastel colors worn by the girls, Ida’s upright posture and the baby’s distance from the ground, and the anxiety obvious on both of the girls’ faces. Elsewhere in the text, it is made clear that the goblins are all male, so the physical space between the goblins and the sisters on the title page can be read not only as an anxiety-bred othering, but also as an intentionally enforced gender divide. Ida’s anxious, serious sideways glance, the tightness of her grip around her sister, and the tension in her feet and shoulders all convey her instinct to protect her sister from the parade of otherworldly goblins. I read this as a sexual anxiety because later in the text, Ida’s first thought upon realizing that the goblins have taken her sister is that they have “stole[n] [her] sister away […] To be a nasty goblin’s bride!” Before she actually discovers them in the middle of a wedding, her explicit goal is to interrupt their “goblin honeymoon”—with its distinct connotation of sexual activity.

It is interesting to put Outside Over There in conversation with Rossetti’s text, not only because of the obvious content-based and underlying thematic similarities, but also because both claim a role as children’s literature. Why do these texts that sensually entrance the young reader (either through imagery or illustration) encompass so much sexual danger for young girls? Why is it the girls’ job to save their sisters, with their parents providing mere oral/anecdotal guidance rather than practical support only after a kidnapping or fruit-buying-encounter has already occurred (Ida’s father sings a song on the sea that guides her to the goblin lair; Lizzie and Laura tells her children and Lizzie’s about the dangers of goblin men—but Ida’s mother dreams absentmindedly of her husband and leaves Ida to take care of the baby, and Lizzie and Laura’s parents never appear in the text)?