How might the history of a publisher bring a book into context—even with no indication of who actually edited it? A Selection of One Hundred and Forty of the Most Favourite English, Scotch, Irish, and American Songs was published by the press of “A. Loudon,” as according to its title page. Archibald Loudon’s deep roots in Carlisle, PA provide a clear outline of his cultural and publishing interests. They even strongly suggest an answer to the mystery of whether he himself edited A Selection, or if he republished the whole collection. One of the few things we can attempt to trace about the book are Loudon’s reasons for publishing it, beginning with the context surrounding his career.

Books were Loudon’s “life-long pursuit” according to historian Eric Fretz. Loudon’s frantic history of inserting himself into early Carlisle’s publishing world reflects this passion: even before the opening of his own publishing press, he participated in the book-loving community of the town. He engaged in book-binding, sold stationary, and was established postmaster of Carlisle in 1802 (Fretz 62). His duties as postmaster were not unimportant tasks, and impacted the spread of information locally. The management of post caused political opinion impact, influenced monetary management, and the title itself indicated a position of high governmental trust. Hungry for more, he officially began his publishing career through a friend: George Kline, who printed Loudon’s publications prior to the opening of Loudon’s press in 1804 (Fretz 62). As for A Selection, it was published by Loudon’s own press in 1806, fresh off the excitement of its opening two years prior.

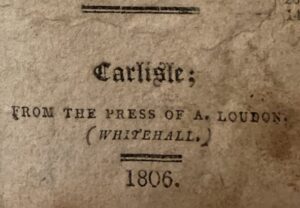

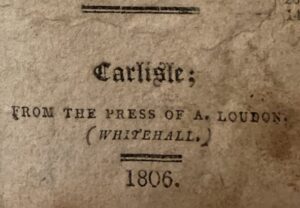

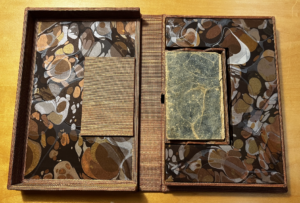

Loudon’s devotion to the literature-world of Carlisle was so intense that despite the small magnitude of his success as a publisher, more than one historian (including Eric Fretz and William A. Hunter) considers him one of the most important printers of early Carlisle. Fretz characterizes Loudon as a “disseminator of early American culture” (Fretz 61), justifying this title by describing his varied publishing interests and role as postmaster. Loudon did, in fact, intend to spread his publications as far as possible, and to do so by appealing to the most popular subjects of the time. Loudon was known to be “keen as to social trends” (Fretz 64), and seemed to attempt to balance these wider social trends with local interests. He spent much of his effort editing his most well-known publications, a series of “true accounts” taken from a number of American-colonial interviewees regarding their encounters with local indigenous American populations. American “frontier” stories were a consistent interest of Loudon’s and of the larger Pennsylvania populace at the time, too: stories of white settlers waging war against Native Americans spread rapidly (Fretz 64). His enthusiasm for spreading local stories continued through the establishment of his own paper, The Cumberland Register, from 1805-1813 (Hunter). But Loudon was also infatuated with the world of art, especially theater. He published a significant number of plays, was a well-known enjoyer of music, and even published the work of a little-known Cumberland County poet, Isabella Oliver (Fretz 62). Loudon was ardent, and his publications from his own press were both edited and printed by him. Considering all this interest in music and theater, A Selection joins the ranks of a large number of artistic publications that Loudon dedicated time to during his career, bearing the obvious mark of his press:

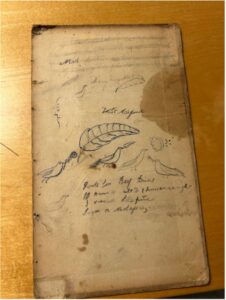

The image above displays the book imprint of A Selection, “Whitehall,” used as Loudon’s imprint from 1805-1809 (Schaumann). The nickname refers to the white walls of Loudon’s press, formerly located at 28 High Street. In fact, his old paper press from the building was obtained by the Cumberland County Historical Society—it hasn’t moved very far! It stands in the museum as a reminder of the early impact of Loudon’s press, and I’ve included an image of it for reference. (For context, the paper press would’ve been used to make paper sheets more even, flat, and dry by pressing. The plaque next to the press includes these details.) The “Whitehall” imprint, displayed clearly in A Selection’s front page, is another bold reminder of Loudon’s press and the pride he took in it.

Another point of pride for Loudon was his ancestry. From what I can tell, it has influenced nearly all of his publication interests, A Selection included due to its inclusion of Scottish and Irish songs in its compilation. In fact, though there is no indication of which songs are of which cultural origin, Eric Fretz identifies the majority as Scottish (63). Loudon’s parents were Scottish immigrants, and moved to America in 1754 (Hunter). Most families in Carlisle during its early history as a town were made up at least in part of Scottish or Irish folks who immigrated to British colonial America. Another significant part of A Selection is American “frontier” songs, ones discussing the founding fathers, military power, and colonization, especially George Washington (Fretz 63). These songs accurately showcase Loudon’s blatant “pioneering” interests (Hunter), and correlate with his most popular publications of stories of war with Indigenous Americans. In fact, Loudon’s family has a history of violent conflict with local Native American populations, attempting first to settle on Indigenous land before relocating, causing Loudon to eventually settle in Cumberland County (Hunter). William A. Hunter notably skims swiftly past the conflict between Loudon’s family and local Indigenous peoples, choosing to focus on how it impacted his future edited story collection. However, there is far more substance to this direct link, including his consistent interest in popular “frontier” stories, his dedication to “disseminating” Scottish/Irish-American colonial stories, and the American songs included in A Selection.

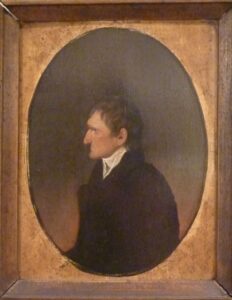

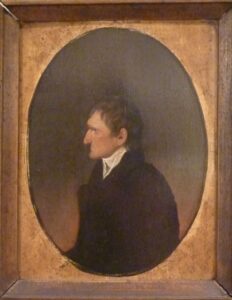

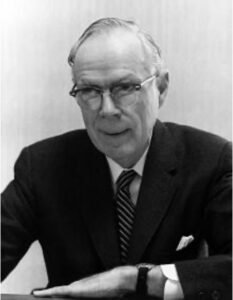

Interestingly, through a Cumberland County Historical Society article on Loudon, I’ve been able to find a portrait of him, as seen above. He appears quite stoic, his expression neutral and focused and his dress professional. He’s perhaps distant, both in his place in the larger space of the portrait and in the way he faces the side, not the front, and does not look at the viewer. There aren’t any extra objects, colors, or lighting included in the portrait, leaving all the focus on Loudon and his impression. From my research, the portrait seems to be an accurate depiction of his hunger for himself and his business to be seen and successful, and this intensity and focus comes across. The portrait, though unrelated to A Selection, makes an interesting addition to supplement Loudon’s familial background, career, and known character.

With those three attributes above for context, it becomes clear why Loudon would take interest in publishing A Selection. But the mystery remains of whether Loudon reprinted the compilation entirely, or edited the selection himself, something that Eric Fretz only touches on briefly as a question (63). To me, however, answering this question is vital to my thinking about my project—so I’ll offer a hypothesis with the above evidence I’ve gathered. Due to Loudon’s personal connections with the cultural origins and topics of the songs included in A Selection, I believe he had some hand in editing the collection. The subject of the compiled songs align with Loudon’s publication history, and with his interest in art and music. This would imply that the “most favourite” songs were Loudon’s own “most favourite,” adding personality and clarity to the book’s title. After all, why would the songs not be some of Loudon’s “most favourite” if he took pride in colonial expansion and his Scottish ancestry?

The main issue with this answer is that Scottish and Irish immigrants made up the majority population of Carlisle. It isn’t impossible that the compilation in its entirety could have existed prior to A Selection’s publication, and suited the interests of another editor or publisher. However, since I am unable to find proof of its existence prior to Loudon’s publication (as are the historians discussing early Carlisle publications), I’ve settled largely into my previous theory. If nothing else, it is a fictitious story that ties Loudon’s history and this book’s publication together in a neat and well-researched bow.

Bibliography:

A Selection of One Hundred and Forty of the Most Favourite English, Scotch, Irish, and American Songs. 1806. SC 398 87 S698.

Dickinson College Archives & Special Collections.

Fretz, Eric. “Archibald Loudon of Carlisle: Disseminator of Early American Culture.” Cumberland County History, vol. VII, no. 2., pp.

61-67. Cumberland County Historical Society.

Hunter, William A. “Archibald Loudon, Pioneer Historian.”1962. C H H947a. Cumberland County Historical Society.

Schaumann, Merri Lou. “Archibald Loudon (1754-1840).” Elizabeth V. and George F. Gardner Library, Cumberland County

Historical Society, gardnerlibrary.org/encyclopedia/archibald-loudon-1754-1840.

Image Credits:

Oil on canvas of Archibald Loudon, painted in 1807 by Cezeron (1952.005.001).

https://gardnerlibrary.org/encyclopedia/archibald-loudon-1754-1840.

Remainder of images taken by iPhone, by author.

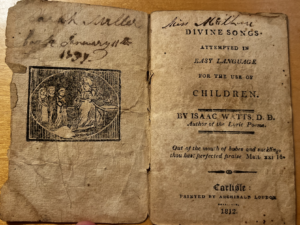

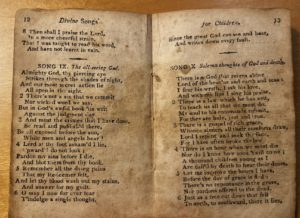

Printed by Archibald Loudon in 1812, Divine Songs is aimed at young, religious readers. The context of the book is straightforward; it has a title page, twenty-eight hymns, and lastly the Ten Commandments. There is nothing else. The children who would have used this book are not interested in anything else, more information or filler is boring to most children. One exception to this is illustrations. There is only one illustration in the book (a frontispiece); it is small, only taking up about a third of the page. Likely no other illustrations were added to keep production costs down, and the final price low as well.

Printed by Archibald Loudon in 1812, Divine Songs is aimed at young, religious readers. The context of the book is straightforward; it has a title page, twenty-eight hymns, and lastly the Ten Commandments. There is nothing else. The children who would have used this book are not interested in anything else, more information or filler is boring to most children. One exception to this is illustrations. There is only one illustration in the book (a frontispiece); it is small, only taking up about a third of the page. Likely no other illustrations were added to keep production costs down, and the final price low as well.

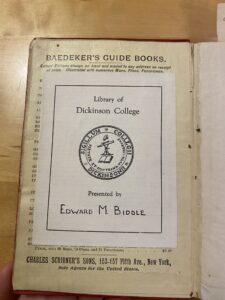

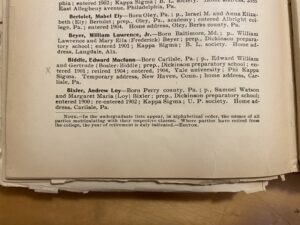

There is also an article on Edward M. Biddle in the file, written for The Dickinson Alumnus. According to this excerpt, his father was E.W. Biddle, a Judge and former president of the Dickinson Board of Trustees. Edward M. became a legal adviser and was an active member of his community. The most important part of this excerpt reads: “As a traveler he has been in Europe a number of times, has visited South America, as well as extended regions of the United States.” This of course indicates a possible use or ownership of this Baedeker’s guidebook, a fact exacerbated by its publication in 1906, soon after his graduation from Yale. This largely eliminates the possibility of the first

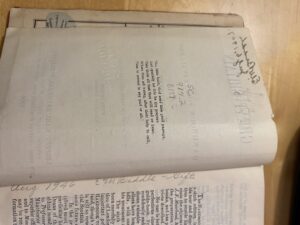

There is also an article on Edward M. Biddle in the file, written for The Dickinson Alumnus. According to this excerpt, his father was E.W. Biddle, a Judge and former president of the Dickinson Board of Trustees. Edward M. became a legal adviser and was an active member of his community. The most important part of this excerpt reads: “As a traveler he has been in Europe a number of times, has visited South America, as well as extended regions of the United States.” This of course indicates a possible use or ownership of this Baedeker’s guidebook, a fact exacerbated by its publication in 1906, soon after his graduation from Yale. This largely eliminates the possibility of the first  inscription in the guidebook being “E.W. Biddle” as opposed to the initially-assumed “E.M. Biddle”… except that E.W. was alive until 1931, when he died unexpectedly at 79. According to the Dickinson College Archives, E.W. was practicing law until 1895, at which point he became the president judge in the Cumberland County Court of Common Pleas. I have already noted the condition of my copy of Baedeker’s Great Britain – it has no annotations or inscriptions within it beyond the two at the beginning of the book, and there is very little wear beyond aging. The only clear indication of use is the broken bookmark, which could be because of age but also because of repetitive use. It is entirely possible to consider that E.W. purchased this book as a way to experience some form of travel from the comfort of his home. He also could have purchased the book as a gift for his son E.M. for graduating from Yale, which he did in 1906, and we know that he travelled. Uncertainty abounds.

inscription in the guidebook being “E.W. Biddle” as opposed to the initially-assumed “E.M. Biddle”… except that E.W. was alive until 1931, when he died unexpectedly at 79. According to the Dickinson College Archives, E.W. was practicing law until 1895, at which point he became the president judge in the Cumberland County Court of Common Pleas. I have already noted the condition of my copy of Baedeker’s Great Britain – it has no annotations or inscriptions within it beyond the two at the beginning of the book, and there is very little wear beyond aging. The only clear indication of use is the broken bookmark, which could be because of age but also because of repetitive use. It is entirely possible to consider that E.W. purchased this book as a way to experience some form of travel from the comfort of his home. He also could have purchased the book as a gift for his son E.M. for graduating from Yale, which he did in 1906, and we know that he travelled. Uncertainty abounds.

1956. The “Dickinson” stamp is most often accompanied by a secondary stamp, which indicates the book’s inventory number: this stamp is missing from

1956. The “Dickinson” stamp is most often accompanied by a secondary stamp, which indicates the book’s inventory number: this stamp is missing from