Christopher Smart (a.k.a. Jack, Kit and Kitty Smart) was a legendary “mad” poet, although his madness was the highly suspect result of tensions within his family, between Smart and his father-in-law, a jealous publisher who imprisoned Smart in an asylum for over five years. The poet was incarcerated again in a debtor’s prison for the final year of his life. Even with this treatment during his short adult life, he managed to produce several of the most remarkable poems of his era: Jubilate Agno and its excerpt “For I Will Consider My Cat Jeoffry,” Song to David, and The Hop-Gaden among others. Smart is primarily remembered today as a religious poet, and his madness is also often seen as the result of a religious mania of a kind that manifested itself as incessant prayer and focus on monomaniacal religious thinking. He spent a number of years affiliated with Pembroke College, Cambridge, during which time he also began running up serious debts that would plague the remainder of his life. During the time of his “madness” he was said to pray out loud and constantly, wherever he happened to be, claiming that an “inner light” connected him directly to the God of Christian revelation.

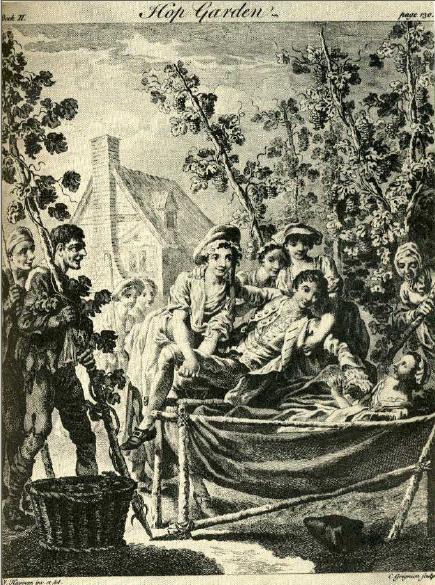

Illustration by Francis Hayman from Smart's "The Hop-Garden," in "Poems on Several Occasions" (1752).

Smart was also a devoted gardener and natural historian. He refers in his writings not only to the Swedish botanist and taxonomist Carolus Linnaeus but also the ancient naturalist Pliny the Elder, even though his effort is most often to reconcile the contemporary science of his era, including Isaac Newton and John Locke, with the “truths” of revealed religion. His Hop-Garden describes an intimate relationship between mankind and the natural world, especially through the mediation of the garden. Written in mock-heroic Miltonic blank verse, The Hop-Garden adopts the Virgilian tradition in its focus on the intersection between human culture and the natural world by way of an emphasis on agriculture.

In her journal, Fanny Burney described Smart as “a man by nature endowed with talents, wit, and vivacity, in an eminent degree.” Others who knew Smart focus on his charm, his wit, and his humanity. As a journalist, he befriended Dr. Johnson, Alexander Pope, and Henry Fielding, among other literary lights of London during the era, and he wrote numerous satires and parodies at a time when these genres were the order of the day.

His poetry is often seen as a forerunner of certain essential aspects of the Romantic writers who would succeed him in the next century. Robert Browning, in his Parleyings with Certain People of Importance in Their Day, suggests that Smart’s madness is, in fact, a subtle and prophetic form of imaginative insight. In addition, Smart’s “madhouse” poems are characterized by their experimentation with form, including the long-line (later employed by William Blake and Walt Whitman) deriving from Biblical verses and the cadences of scriptural language, and various forms of repetition–including call-and-response–that look forward to the 20th century. In addition, the sensuous immediacy of a poem like “For I Will Consider My Cat Jeoffry” (from Jubilate Agno) echoes elements of poets like Blake, Keats, and Alan Ginsberg:

For the Electrical fire is the spiritual substance, which God sends from heaven to sustain the bodies both of man and beast.

For God has blessed him in the variety of his movements.

For, tho he cannot fly, he is an excellent clamberer.

For his motions upon the face of the earth are more than any other quadruped.

For he can tread to all the measures upon the music.

For he can swim for life.

For he can creep.

Smart died in obscurity at age 49 and much of his work was lost until the 20th century. Jubilate Agno, perhaps now his best known work, was not published until 1939.

Smart links:

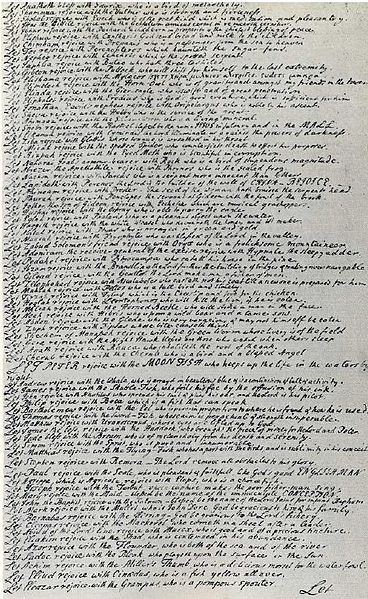

This manuscript, from Smart's "Jubilate Agno," suggests one pathology of his "madness" with its repeated "Let"-phrases (and comparable "For"-phrases) at the start of each line and an obsessively methodical quality in the actual handwriting; the manuscript goes on like this for pages.

Christopher Smart in Slate: Robert Pinsky reads and comments on the modern relevance of the “mad” poet in “In Nomine Patris et Felis: Christopher Smart’s extremely spiritual poem about his cat.” Slate (October 6, 2009)

Smart on the Poetry Foundation site: Karina Williamson, of St. Hilda’s College, Oxford, and University of Edinburgh, notes that: “It is notable that beginning with Robert Browning, it has been poets rather than critics who have been the warmest and most perceptive admirers of the poetry of Christopher Smart. In a 1975 radio broadcast in Australia, Peter Porter spoke of Smart as “the purest case of man’s vision prevailing over the spirit of his times.” While it would be facile and unilluminating to characterize Smart as a proto-Romantic, there can be no doubt that the combination of visionary power, Christian ardor, and lyrical virtuosity in his finest poetry was unappreciated and unmatched in his own age.”

Benjamin Britten’s Rejoice in the Lamb draws its libretto text from Smart’s Jubilate Agno: “Britten’s Rejoice in the Lamb, or Festival Cantata, was written for the 50th anniversary of the consecration of St. Matthew’s Church in Northampton. It was commissioned by the former Vicar, the Very Reverend Walter Hussey. The piece was first performed on September 21, 1943 . . . The eighteenth-century poet was in an insane asylum when he wrote it, and although there is a delightful sense of madness in the poem, the religious character of the work is the most striking. The manuscript is not complete, and the fragments of it were not found until 1939. Their discoverer, William Stead, published them under the name “Rejoice in the Lamb.” Britten chose ten of the most celebratory and religious sections to set to music.”

Robert Browning’s Parleyings with Certain People of Importance in Their Day: A Victorian conversation with Christopher Smart, in verse, imagined by Browning.