Jennifer Lindbeck, Class of ’98 Dickinson College, and Ashton Nichols, Department of English

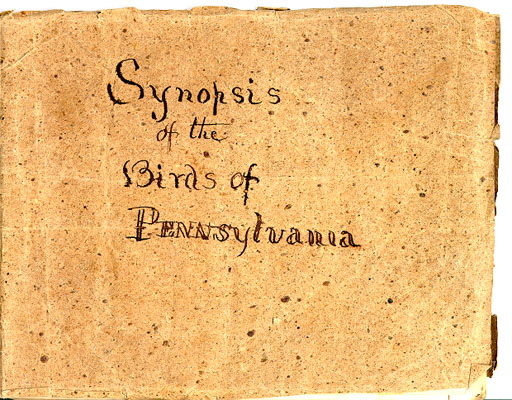

Cover to Baird's field notebook in Dickinson College archives. See image (lower left) for a page of the journal with its bird-watching entries.

Spencer Fullerton Baird was born in Reading, Pennsylvania, in 1823. He attended West Nottingham Academy near Port Deposit, Maryland. He entered Dickinson College at the age of 13 and received a bachelor’s degree in 1840 and a master’s degree in 1843. By 1842, he had collected 650 bird skins representing 128 different species. While still a student at Dickinson, he began corresponding with John James Audubon and other leading ornithologists and naturalists of the day. In the fall of 1846, he was appointed Professor of Natural History and Curator of the Museum (the extensive natural history collection) at Dickinson.

Baird was among the first professors in America to teach students in the field and to use active learning as a central part of his pedagogy. He collected specimens widely in Carlisle and the Cumberland Valley. He sometimes worked with his older brother, William, on the the field study and identification of new and disputed species. William Baird, who went on to become a lawyer, contributed over 3,000 natural history specimens to his brother’s collection. Baird also helped to establish field and laboratory research, as well as careful record keeping, as the basis of museum work in natural history. He sent Audubon a yellow-bellied flycatcher that turned out to be a new species. Audubon, in return, gave the greater part of his collection of birds to Baird and also named Baird’s bunting (now Baird’s sparrow) after him. Other naturalists with whom Baird worked included Louis Agassiz, Asa Gray, George Newbold Lawrence, John Cassin, and Thomas M. Brewer. In 1850, at the age of 27, Baird was appointed Assistant Secretary of the recently formed Smithsonian Institution. When he departed from Carlisle, Baird transported two boxcars full of specimens from the Cumberland Valley with him: stuffed European and American mammals and skins, botanical specimens, vertebrate skeletons, and fossils. The collection he took included well over

Notebook entries for Cooper's Hawk, Black Hawk, and Short Winged Buzzardfour thousand bird skins, reptiles and fish in solution, and boxes filled with bird's nests and eggs. Parts of this collection are still held by the Smithsonian in Washington. As the Smithsonian website on Baird notes,

four thousand bird skins, reptiles and fish in solution, and boxes filled with bird’s nests and eggs. Parts of this collection are still held by the Smithsonian in Washington. As the Smithsonian website on Baird notes,

Scientists such as Baird believed it was imperative to study that natural distribution of flora and fauna before it disappeared. The distribution of such life forms would be studied to uncover the great laws governing life, especially to evaluate Charles Darwin’s recently published theory on the Origin of Species. And the economic development of the country would be spurred by scientific collection and analysis of the natural resources of each region. For a collector such as Baird, each specimen was a piece of a puzzle, which when compared, contrasted, juxtaposed and arranged systematically, contributed to a larger picture of the order underlying nature.

In 1868, he published a four volume series that catalogued all known North American bird species. Ten years later, Baird became Secretary of the Smithsonian upon the death of Joseph Henry, the first leader of the emerging national institution. It was Baird, however, who became one of the first naturalists in America to argue for the careful study of the already vanishing natural landscape of the United States. Even in the mid-nineteenth century, he anticipated the potential for human destruction of natural habitats.

Then in 1871, Baird’s next major appointment made him commissioner of the newly formed Commission on Fish and Fisheries. This forward-looking branch of the government office that would become the U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service, was established–even at this early date–in order to track and argue for fish species and fish stocks that were already declining in the latter decades of the 19th century. Two years later, Baird published an 850-page Report on the Condition of Sea Fisheries of the South Coast of New England, a work that suggests how diligently he worked at all of his professional activities. He became Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution in 1878, only the second person to lead this national museum and research institution. Baird died in 1887 in Woods Hole, Massachusetts, at the summer fish station that he had had helped to establish there fifteen years earlier.

Today, there is a fish-stocking ship in the Great Lakes named the M/V [Motor Vessel] Spencer F. Baird. According to its webpage, “The M/V Spencer F. Baird is a one-of-a-kind hatchery stocking vessel in the Great Lakes. With its modern equipment and improved assessment capability, the Baird will expand Service’s ability to meet its own information and research needs, as well as those of state, tribal, provincial and federal partners.” Facts about the vessel include, “The M/V Spencer F. Baird is a fish stocking and stock assessment vessel operated by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service on the Great Lakes. The 95-foot motor vessel is one of two Service vessels of this size designed and outfitted for extensive fisheries conservation work. Of 63 science vessels on the Great Lakes, the Baird is the only hatchery fish distribution vessel in operation.” For its lake trout restoration project,

The Baird’s primary mission is to transport fingerling and yearling lake trout raised at Service hatcheries in Wisconsin and Michigan to restore lake trout populations in lakes Huron and Michigan. The Service produces almost 4 million lake trout each year; it transports 95 percent of these fish to important offshore sites for release. Offshore stocking results in better survival; it also increases the probability that lake trout will spawn at offshore habitats near stocking locations. The configuration and support systems of the Baird ensure optimal water and oxygen conditions for lake trout during the ride from shore to stocking sites. Each year, the Baird will travel 2,500 miles in lakes Huron and Michigan during a 60-day period from April to June.

So Spencer F. Baird remains a very active presence in the government’s fisheries operation.

Spencer Fullerton Baird links:

Baird’s report as curator to Dickinson College (1846)

Baird and the Growth of a Dream (Smithsonian website)

Baird at Dickinson College: field notebook

Baird’s Sparrow: A creature in danger who is hard to keep track of or to save.