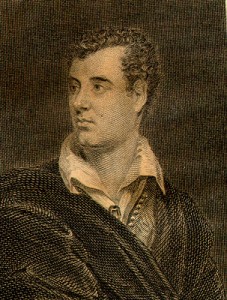

George Gordon, Lord Byron may have referred to Erasmus Darwin as “that mighty master of unmeaning rhyme” (“English Bards and Scotch Reviewers” [1809]), but Byron’s poetry helped to construct a version of the natural world that affected readers throughout the nineteenth-century. His extensive travels brought him into contact with parts of the world that were little known to most Europeans before they read Byron’s verse descriptions, and his wry cynicism often led him to compare human beings (unfavorably) with lower forms of life. Byron was also a master of descriptive, and satiric, language that connected the animal kingdom with human affairs, as in this extract from his journal for 14 November 1813 recounting a visit to the Exeter ‘Change Menagerie in the Strand in London:

George Gordon, Lord Byron may have referred to Erasmus Darwin as “that mighty master of unmeaning rhyme” (“English Bards and Scotch Reviewers” [1809]), but Byron’s poetry helped to construct a version of the natural world that affected readers throughout the nineteenth-century. His extensive travels brought him into contact with parts of the world that were little known to most Europeans before they read Byron’s verse descriptions, and his wry cynicism often led him to compare human beings (unfavorably) with lower forms of life. Byron was also a master of descriptive, and satiric, language that connected the animal kingdom with human affairs, as in this extract from his journal for 14 November 1813 recounting a visit to the Exeter ‘Change Menagerie in the Strand in London:

Two nights ago I saw the tigers sup at Exeter ‘Change. Except Veli Pacha’s lion in the Morea,–who followed the Arab keeper like a dog,–the fondness of the hyaena for her keeper amused me most. Such a conversazione! — There was a “hippopotamus,” like Lord L[iverpoo]l in the face; and the “Ursine Sloth” hath the very voice and manner of my valet–but the tiger talked too much. The elephant (see Chunee) took and gave me my money again–took off my hat–opened a door– trunked a whip–and behaved so well, that I wish he was my butler. The handsomest animal on earth is one of the panthers; but the poor antelopes were dead. I should hate to see one here:–the sight of the camel made me pine again for Asia Minor.

Byron’s attitude toward the nonhuman world was as complex as his view of human society.

Although usually hostile to the pantheistic–God-in-Nature–strains he identified in the early poems of Wordsworth, Byron was willing to admit that he had been “doused” with Percy Shelley’s Wordsworthianism during the summer the two younger poets spent together in Switzerland in 1816. The result of this famous Shelley-Byron Alpine alliance were lines in Canto III of Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage that were as naturalistic as any Byron ever wrote: “I live not in myself, but I become / Portion of that around me; and to me, / High mountains are a feeling” (3: 72). Later in this same canto, he is willing to admit a connection between the human heart and the natural world that is antithetical to a proto-existentialism that is often identified with the cynical Byronic pose: “Are not the mountains, waves, and skies a part /Of me and of my soul, as I of them? / Is not the love of these deep in my heart / With a pure passion? (75). This Shelleyan version of Wordsworth was not to last in Byron’s own heart for long, however, as he confessed to his journal during the September following the Frankenstein summer:

I am a lover of Nature – and an Admirer of Beauty – I can bear fatigue – & welcome privation – and have seen some of the noblest views in the world. – But in all this – the recollections of bitterness – & more especially of recent & more home desolation – which must accompany me through life – have preyed upon me here – and neither the music of the Shepherd – the crashing of the Avalanche – nor the torrent – the mountain – the Glacier – the Forest – nor the Cloud – have for one moment – lightened the weight upon my heart – nor enabled me to lose my own wretched identity in the majesty & the power and the Glory – around – above – & beneath me (Journals 5: 104-05)

The more characteristic Byronic attitude toward nature is evidenced in a poem like Mazeppa, the verse tale that recounts the story of Ivan Mazeppa (1639-1709), a Ukranian soldier-hero who, after an illicit affair with the Orientalist wife of a count, is punished by being tied naked to a horse and released into the wild. The bulk of the poem recounts Mazeppa’s tortures as the horse charges across Eastern Europe, facing the miseries of heat and cold, dry and wet, a natural world that is mostly about terror and human suffering: “The tortures which beset my path, / Cold, hunger, sorrow, shame, distress, / Thus bound in nature’s nakedness” (Stanza 13). The complexity of Byron as nature-poet is perhaps surprisingly evident in one of his most often-quoted lyrics: the epitaph he penned for his beloved Newfoundland dog Boatswain which includes these misanthorpic, if naturalistic and equally heartfelt, lines:

Near this Spot

are deposited the Remains of one

who possessed Beauty without Vanity,

Strength without Insolence,

Courage without Ferocity,

and all the virtues of Man without his Vices.This praise, which would be unmeaning Flattery

if inscribed over human Ashes,

is but a just tribute to the Memory of

BOATSWAIN, a DOG,

who was born in Newfoundland May 1803

and died at Newstead Nov. 18, 1808.. . . the poor dog, in life the firmest friend,

The first to welcome, the foremost to defend,

Whose honest heart is still his master’s own,

Who labors, fights, lives, breathes for him alone,

Unhonored falls, unnoticed all his worth,

Denied in heaven the soul he held on earth.

While man, vain insect, hopes to be forgiven,

And claims himself a sole, exclusive heaven.

Oh man! thou feeble tenant of an hour,

Debas’d by slavery, or corrupt by power,

Who knows thee well must quit thee with disgust,

Degraded mass of animated dust!

Thy love is lust, thy friendship all a cheat,

Thy tongue hypocrisy, thy heart deceit,

By nature vile, ennobled but by name,

Each kindred brute might bid thee blush for shame.

Ye! Who behold perchance this simple urn,

Pass on, it honours none you wish to mourn.

To mark a friend’s remains these stones arise,

I never knew but one – and here he lies. (“Epitaph to a Dog”)

Conversations among Byron, Percy Shelley, and Mary Shelley led Mary to the dream (“a saw the pale student of the unhallowed arts kneeling beside the thing he had put together”) that became the genesis of Frankenstein. Byron’s satiric cynicism may be closer to the courtly Augustan nuances of Alexander Pope than the woodland wilds of Wordsworth, but his careful attention to the details of his surroundings was an essential part of the rhetoric of poetic naturalism that came to pervade the nineteenth century.

Byron links:

Mazeppa gazes upward at the raven that is waiting to make a meal of him after his torture--tied to the back of a horse--ends.

Byron quotes on the natural world (poetry and prose extracts)

Childe Harold, Canto III : the Wordsworthian/Shelleyan influence (University of Adelaide [AU] e-books)