Monument in the graveyard at Stoke Poges, in Buckinghamshire, UK, the site where Gray began composing his famous elegy. This would also become the location of Gray's own burial, next to his mother, on August 6, 1771.

Thomas Gray is another forerunners of the Romantic movement in British literature. Although much of his poetry fits well into the conventions of 18th-century English verse, his sense of specific places, his emphasis on the picturesque, his naturalistic observations, and his focus on certain psychological states of the human mind all link him to the foundational techniques of poets like Wordsworth, Coleridge, Shelley, and Keats. Gray was born in London on the day after Christmas in 1716, and he attended Eton College (a high school in England in that era), where he befriended Horace Walpole, Richard West, and Thomas Ashton. He went up to Peterhouse College Cambridge, where he eventually became a fellow, and then a fellow of Pembroke College, a scholar of the classics, and eventually the Regius Chair of Modern History at Cambridge, in 1762. he was a scholar’s scholar who life was lived in the library and his rooms at Cambridge, although he did travel widely on the continent with his friend Walpole, the son of Robert Walpole, Prime Minister of England from 1721 to 1742.

Gray was a founder of the Graveyard School of poetry, a title bestowed primarily for his “Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard,” one of the most famous, most frequently anthologized, and most often-quoted poems in the tongue. For a lyric its length (124 lines), it has produced more memorable phrases–and literary references–than perhaps any other poem: “the curfew tolls the knell of parting day,” “the paths of glory lead but to the grave,” “Some mute, inglorious Milton,” “Far from the madding crowd,” “kindred spirit,” etc. The poem captures a combined sense of the fleetingness of life, the mortality of the physical self, and the fragility of all human life that would become a hallmark of the Romantic poets of the next century.

Inscription on the grave of Thomas Gray in Stoke Poges churchyard, the site where he began composing "Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard," first published in 1751.

Gray’s poems invokes a “glimmering landscape” and an atmosphere of “solemn stillness” that includes the beetle who “wheels his droning flight” and the “drowsy tinklings” of the cows bell in the distant fields. Linguistic richness combines with nonhuman details–“moping owl,” “rugged elms,” “yew-tree,” “swallow twittering”–and images from a world of men and women: “ivy-mantled tower,” “forefathers of the hamlet,” “straw-built shed,” and “blazing hearth,” to produce a powerful sense of humankind and animals linked closely, and of thing and thought mixing, not “strangely,” as Wordsworth would say half-a-century later, but rather naturally, in a perfect harmony of time and space and circumstance. When Keats’s gathering swallows “twitter in the sky” at the close of “To Autumn,” when Wordsworth’s speaker in “The Boy of Winder” stands “Mute–looking at the grave in which” the young boy “lies,” when Shelley (describing the tomb of Keats) thinks of those who die unknown, who sink, “extinct in their refulgent [i.e. shining, radiant] prime,” these poets are all harking back to Gray’s elegy, to a country graveyard where “heaves the turf in many a mouldering heap, / Each [person] in his narrow cell for ever laid,” where “The boast of heraldry, the pomp of power, / And all that beauty, all that wealth e’er gave, / Awaits alike th’ inevitable hour:–.” All of these Romantic poets are secure in their own knowledge that, whatever poetry they may write during their own, too-often foreshortened lives, the truth of their own imagined graveyards is the truth of every actual grave; as Thomas Gray so well said: “Some mute inglorious Milton here may rest.”

Gray links:

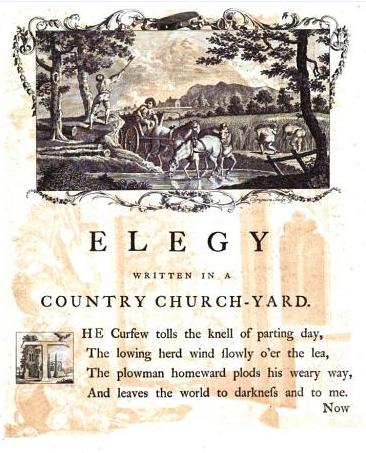

The opening page of an illustrated edition, published by Robert Dodsley. Richard Bentley is the illustrator and the image, reminiscent of Thomas Bewick, combines nature and culture in agricultural harmony.

Frontispiece to the 1753 edition of the poem. Images like this, and the one in the Dodsley illustrated edition (left), helped to prepare the way for the coming "Romantic" movement in landscape and nature poetry.

The Thomas Gray Archive (Oxford University): a remarkably thorough “Collaborative Digital Collection”

Thomas Gray (1716-1771): A site from the Luminarium Anthology of English Literature