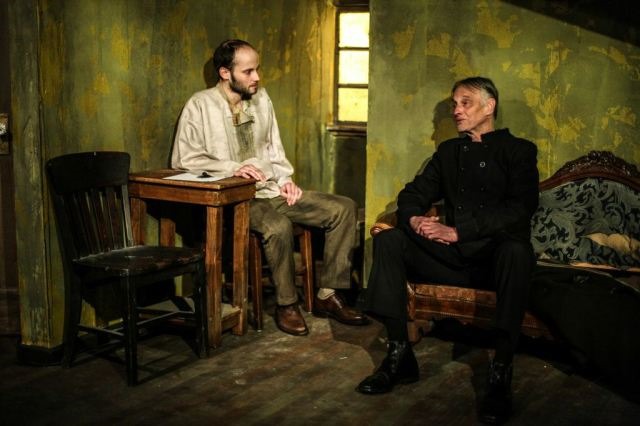

Reading Gilman’s The Yellow Wallpaper has completely changed my reading of my favorite novel, Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment: Namely, that “yellow wallpaper” is a theme of principle importance in Dostoevsky’s novel. The protagonist of Crime and Punishment, Raskolnikov, is a poor student who lives in a small attic room in St. Petersburg. Early on in the novel, he murders the local pawn broker as well as her sister (though only the first is premeditated). The question that scholars have grappled for years is, what was Raskolnikov’s motive for murder? I believe it can be argued that his yellow wallpaper is what drove him to his crime.

In Crime and Punishment, all of the character’s rooms coincidentally have yellow wallpaper: Raskolnikov’s; Aloyna Ivanovna’s, the pawn broker he murders; Sonya’s, the prostitute who seeks to redeem him; and even the hotel rooms. Dostoevsky describes Raskolnikov’s room as having “yellow dusty wall-paper peeling off the walls that gave it a wretchedly shabby appearance” (23). Yellow wallpaper is something the characters cannot escape. And like Jane in The Yellow Wallpaper, Raskolnikov is obsessed with wallpaper.

After committing murder and returning to his room, Raskolnikov immediately stuffs what he has stolen into his wallpaper. This causes him undue anxiety due to its conspicuousness; he later removes the stolen goods and tosses them under the bridge in the water, not really wanting what he had stolen in the first place. What struck me as significant after reading Gilman’s work is Raskolnikov’s strange fixation on wallpaper. For instance, when visitors come to visit Raskolnikov he turns away from them on his bed and stares at the wall instead:

“Raskolnikov turned to the wall, selected one of the white flowers, with little brown lines on them, on the yellowish paper, and began to count how many petals it had, how many serrations on each petal and how many little brown lines. He felt his arms and legs grow numb as if they were no longer there. He did not stir, but looked fixedly at the flower.” (Dostoevsky 114)

It seems here that Raskolnikov has become a victim to the wallpaper, as if it is overtaking him. The more he absorbs himself in it, the number he feels. This numbness does not seem to be comforting but excruciating—we see this when Raskolnikov finally turns away from the wallpaper:

“[Raskolnikov’s] face, now that he had turned away from the engrossing flower on the wallpaper, was extraordinarily pale and had an expression of intense suffering, as though he had just undergone a painful operation or been subjected to torture.” (Dostoevsky 122)

Compare this with Jane’s similar quote in The Yellow Wallpaper:

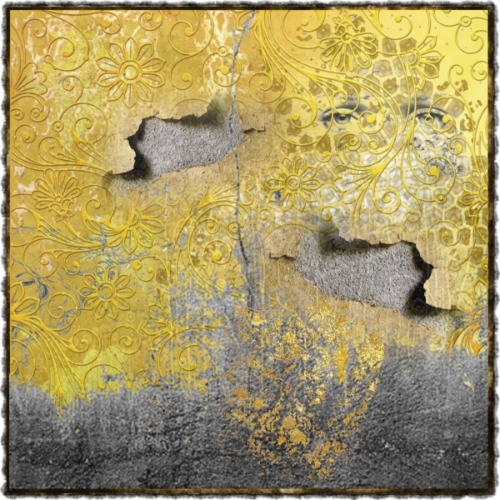

“The color is hideous enough, and unreliable enough, and infuriating enough, but the pattern is torturing.” (Gilman 9)

The wallpaper has a hypnotic but toxic quality. Like a bee drawn to nectar, Raskolnikov is drawn to the flower—it compels and traps him. And like Jane, he seems to become lost in the intricate haphazardness of its design.

Though yellow wallpaper causes Raskolnikov undue pain and suffering, for some reason, he finds himself fond of it. We see this when he returns to the flat of the pawn broker he killed:

“[The workmen] were putting new paper, white, with small lilac-colored flowers, on the walls, in place of the old, rubbed, yellow paper. For some reason Raskolnikov violently disapproved of this, and he looked with hostility at the new paper, as though he could not bear to see it all changed.” (Dostoevsky 146)

This is an oddly strong reaction that Dostoevsky never explains. Raskolnikov’s attitude is comparable to Jane’s, who at one point states that she is fond of her room “in spite of the wallpaper. Perhaps because of the wallpaper” (Gilman 6). Both characters are at first tormented by their wallpaper, but later come to enjoy it as a source of familiarity. Even though Raskolnikov commits the murder in order to escape the yellow wallpaper that suffocates him, he comes to approve of it in the end. This all seems to illuminate the madness that wallpaper truly is. For what is wallpaper but a form of masking, of hiding what is really underneath?

Dostoevsky, Feodor. Crime and Punishment. Norton Critical 3rd Ed. Translated by Jessie Coulson and edited by George Gibian. W.W. Norton & Company: 1989.