by Benjamin Fleming

PLOT SUMMARY

In AD 117, Rome controlled most of the known world, but it could not control everything. Rome’s frontiers were hotbeds of uprisings and rebellions that could only be snuffed out by the full might of the Roman military. It is in this harsh climate that the movie Centurion (2010) is set. The film opens a harsh and foreboding landscape of crags and ice-covered valleys. Slowly it focuses on a lone figure running for his life, stumbling along the snowy mountaintop. The story is told in retrospect by the main character and opens with his narration, “My name is Quintus Dias, I am a soldier of Rome, and this is neither the beginning nor the end of my story,” before flashing back two weeks (Centurion 3:00-3:57). Centurion Quintus Dias (Michael Fassbender) was stationed at the Roman outpost of Inch-Tuth-Il, located in modern Scotland, when a Pict war-band attacked the outpost under the cover of darkness. The unprepared legionaries were massacred, save for Centurion Dias (Centurion 3:58-6:50).

Around this time, the general of the Legio IX Hispania stationed at York, Titus Flavius Virilus (Dominic West), receives a dispatch from Governor Julius Agricola (Paul Freeman) ordering the 9th Legion to prepare for war (Centurion 6:51-10:02). Dias, meanwhile had been taken to a Pict village. There he is tortured and interrogated by the Pict King Gorlacon (Ulrich Thomsen) for information on Roman troop movements (Centurion 10:05-11:46). As Dias is being tortured, General Virilus is meeting with Governor Agricola who outlines the plans for the mission. Rome is on the verge pulling forces out of Britain and he is looking to make one final attempt to conquer the north before those orders arrive. Doing so, he argues, would bring wealth, fame, and honor to them all; despite this appeal, General Virilus states, “My men have honor enough.” Agricola threateningly responds, “Enough to disobey a direct order?” General Virilus gives in to Agricola and is detailed a local tracker named Etain (Olga Kurylenko) to lead the legion to Gorlacon (Centurion 11:50-14:00).

As the legion moves out, Dias escapes and attempts to make it back to Roman territory; on the way he meets up with the legion. Since Dias has just escaped Gorlacon, General Virilus asks him to lead them back to the village from which he escaped (Centurion 14:30-21:25). Unknown to the general, Etain is a double agent for the Picts. She leads the legion into an ambush in the forest where General Virilus is captured and only seven men escape with their lives: Quintus Dias, Thax (JJ Field), Bothos (David Morrissey), Brick (Liam Cunningham), Leonidas (Dimitri Leonidas), and Tarax (Riz Ahmed). As the survivors survey the dead, Dias speaks to the audience as narrator, “In the chaos of battle… it is easy to turn to the gods for salvation, but it is soldiers who do the fighting and soldiers who do the dying, and the gods never get their feet wet” (Centurion 22:30-29:13).

Because of honor and duty, the survivors set off to try to rescue the General from the grasp of Gorlacon. Arriving at night, they sneak into the village and try to break the General out of his chains, but fail, due to a war-band returning. During their retreat from the village, Thax unknowingly kills Gorlacon’s son (Centurion 30:00-35:00). The Romans are pursued by trackers led by Etain; knowing they will die unless they make it back to Roman lines, they attempt to lose the following Picts (Centurion 44:00-55:30). As they run, Dias explains to the audience, “My father taught me that in life, duty and honor matter above all things, a man without his word is no better than a beast. I made a promise to the general to get his soldiers home; that is my task; that is my duty” (Centurion 51:00-52:00). Eventually, the trackers catch up to the fugitives along a cliff face. The Romans all jump off into a river below, save for Tarax, who is killed. Jumping into the river, though, causes them to be separated into two groups: Bothos, Dias, Brick, and Leonidas in one, and Macros and Thax in the other. Macros and Thax are chased by wolves, until Thax sacrifices Macros to save himself. Meanwhile, Dias’s group is harassed by the trackers. Bric and Dias attack the trackers camp killing all the trackers there in an attempt to even the odds; however, the Romans later learn some of the trackers led by Etain attacked their camp at the same, leading to the death of Leonidas (Centurion 55:40-1:04:00).

Continuing to run, Dias, Brick, and Bothos stumble on the house of a “Necromancer,” named Arianne (Imogen Poots), who houses them, treats their wounds, and hides them from Etain (Centurion 1:04:04-1:16:30). After resting up, the three set out for a nearby Roman outpost. Once they reach it, they find it abandoned with a notice that Emperor Hadrian has ordered a new defensive line to be formed south of the outpost. Knowing they cannot run from Etain any longer, they set up defensively inside the fort and wait for her now small force to attack. When they do, the Romans manage to kill the Picts, including Etain, though Brick dies during the fighting (Centurion 1:17:10-1:24:40).

Finally, after weeks on the run the soldiers near Roman territory. As they approach, they run into Thax and he rejoins them. Nearing an under-construction wall, Thax and Dias get into a fight, where Dias kills Thax, because Dias realized what Thax had done to Macros. While this is happening, Bothos over-eagerly makes for the wall and is mistakenly identified as a Pict and shot dead (Centurion 1:25:00-1:30:27). As the only survivor, Quintus Dias is escorted to Governor Agricola to be debriefed. Explaining what happened, Dias is congratulated by Agricola as a hero, but after he leaves the room Agricola’s daughter Druzilla (Rachael Stirling) turns to Agricola and says “We cannot return to Rome in disgrace, better that the fate of a legion remain a mystery than for their failure to be known.” Agricola, immediately agrees with her and takes it one further, “If word gets out, every nation would rise against us.” He has his daughter arrange Dias’s death (Centurion 1:30:30-1:31:36). Quintus sees it coming though; killing his assailants he escapes to the wilds where he returns to Arianne to live out his days (Centurion 1:31:39-1:33:11). In a parallel to the beginning, the story ends with it snowing and Quintus Dias announcing, “My name is Quintus Dias, I am a fugitive of Rome and this is neither the beginning nor the end of my story” (Centurion 1:33:11-1:33:25).

ANCIENT BACKGROUND

This film is about the disappearance of the Legio IX Hispana (the Ninth) in the wilds of Britain. This legend has captivated minds since around 1732, when John Horsley’s Britannia Romana: The Roman Antiquities of Britain was published. In it, Horsley used Roman records to identify the Roman legions stationed in Britain, noting the disappearance of the Ninth from records between the time of Tacitus and the reign of Hadrian (Manea). One of the reasons the disappearance from the records is baffling, is because the Legio IX Hispana was a famous and elite Roman legion created by Pompey and put into service by Julius Caesar (Lendering). Since Horsley published there has been an ongoing scholarly debate about the fate of the Ninth. Dr. Miles Russell, senior lecturer in Prehistoric and Roman Archaeology at Bournemouth University, contends that the Ninth was wiped out. He cites three pieces of evidence that a disaster of some kind occurred in Britain around AD 118. First, the Roman writer Fronto commented on the large number of Roman soldiers killed in Britain during Emperor Hadrian’s reign in a letter to Marcus Aurelius, indicating some type of heavy fighting. Second, there is a tombstone from Ferentinum, Italy, that describes “emergency reinforcements of over 3,000 men [that] were rushed to the island on ‘the British Expedition’,” early in Hadrian’s reign. His last piece of evidence is that when Hadrian visited Britain, “to correct many faults,” around AD 122, he brought with him the Sixth legion (Legio VI), which was stationed at York (York was the Ninth’s was last documented posting in AD 108). To Dr. Russel, the Sixth’s move to York implies a replacement or replenishing of the Ninth. Evidence against this was discovered by archaeologists in 1959. Archaeologists found stamped bricks in Germania dating to after the supposed destruction of the legion around AD 118 (Manea). This discovery gave credence to the argument that the legion was not destroyed in Britain, but was relocated to other parts of the empire. Without written records of troop transfers, it is difficult to confirm conclusively one way or the other.

It is within this ambiguity that the story of Centurion exists. When asked why he decided to write about the destruction of the Ninth, even without actual proof, director Neil Marshall replied that, though modern historians tend not to believe the Ninth was destroyed, “I like the myth and I stuck with that” (“Centurion- Neil”). In writing the story Marshall took lots of creative license. One major example is the anachronism of including Governor Agricola. Agricola died in AD 93, almost 24 years earlier (Tacitus l). The real governor of Britain at the time most likely would have been either Marcus Appius Bradua or Quintus Pompeius Falco (Everitt 185, 216). Marshall’s stated inspiration in creating the script was that, “I’d really like to know what could’ve potentially happened to them if this [legend] was real” (Zimmerman). The inclusion of Agricola would at first seem counter-productive, but if one looks at how the addition fits contextually, the move begins to make sense.

The legend of the Ninth states that it was ordered north to put an end to raiding in the Caledonia region of northern Britain. This situation parallels the sixth year of Agricola’s governorship as described by Tacitus. During that year, Agricola faced an uprising centered in Caledonia, and moved his army north to combat them. At one point, a large force of Britons surprised the Ninth legion at night, causing severe losses within the legion (Tacitus 25-26.3). In essence, to create a realistic set of events, Marshall took a similar, factual occurrence and placed it within the confines of the legend, trimming the actual event to mesh with the myth.

The film also takes license with Agricola’s his character. In Centurion, Agricola is concerned with gaining fame and creating a long-lasting legacy. This is seen explicitly during his conversation with General Virilus about mobilizing the Ninth (in which he admits that he wants to be the orchestrator of the final conquest of Britain) and at the end when he fears for his legacy and tries to have Quintus Dias silenced (Centurion 6:51-10:02 and 1:30:30-1:31:36). Tacitus’s Agricola presents the governor in almost complete contrast to the film. Tacitus summarizes his view of Agricola’s character as living a “style of life [that] was modest…. As a result, most people, who always measure great men by their display, when they saw or noticed Agricola, asked why he was famous” (Tacitus 41.4). He “did not exploit his success to glorify himself… he disguised his fame…” (Tacitus 18.7). The difference in characterization can be attributed to the role of Agricola in each situation. For Tacitus, Agricola was his father-in-law, so emphasizing Agricola’s virtues was not only a facet of the medium of biography, but also beneficial to himself and his legacy. In Centurion, Agricola was needed to represent the corruption of politicians who use soldiers as pawns to advance themselves.

Another opportunity for artistic license was the depiction of the northern Britons. The tribes of northern Briton are difficult to recreate due to the lack of archaeological evidence about them. The northern Britons are called Picts in the film and they speak Scots Gaelic (Holden), but “Picts aren’t identified in the historical record until AD297, when they crop up in a panegyric by the Roman orator Eumenius,” (Tunzelman) and historians do not know the language the northerly Britons spoke. It would have been most accurate to call the northern people Caledones, after the people referenced in Tacitus, but historians still know no more about them. The only contemporary description is a generalization of all Britons by Tacitus who described them as being more ferocious than their Gaulish counterparts, yet able to be very obedient, but still refusing to be slaves. As for their military and governmental structure, “their infantry is their main strength” and “they are formed into factional groupings by the leading men” (Tacitus 12.1) Interestingly, “they even do not distinguish between the sexes when choosing commanders” (Tacitus 16.1). Even though they are called Picts, the film manages to capture these traits, specifically in Etain’s character—who obeys the Romans for a time but will not be a puppet to destroy her own people— and in how the Pict hunters follow her unquestioningly.

One of the most accurate aspects of the entire movie is its depiction of the mood of Rome towards the frontiers, including Britain. Governor Agricola comments at one point that Rome is beginning to pull out of Britain and it is later shown in the notice found by Quintus Dias in the abandoned outpost (Centurion 6:51-10:02 and 1:17:10-1:18:00). This mood of creating a more defensible frontier at the loss of some land was strong within the Roman Empire around AD 117 as Hadrian ascended to the throne. Hadrian began to put into a practice a strategy called “imperial containment” that limited the size of the empire, gave up indefensible territory, and created defensible frontiers as shown by Hadrian’s Wall (Everitt xxiii and 224-225).

MAKING THE MOVIE

Director Neil Marshall has gone on record saying that the film Centurion was 10 years in the making. One night he “was sitting in a bar with a mate of [his] and having a few drinks… and [his friend] mentioned to [him] this legend that he’d heard of, of the Ninth legion of Rome –

this entire legion of Roman soldiers that marched into Scotland in 117 AD and vanished without a trace…. I was instantly hooked. I thought, ‘This is going to make a great movie’” (Zimmerman). The next couple of years saw him working on the script. Originally, he considered a sort of supernatural, fantastic element but decided to keep it grounded in history. According to Marshall, “I came up with this whole story based on what might have actually happened to the Romans… and then actually, it’s the Romans that create the myth as a cover-up for their own screw-up” (Zimmerman).

As the script started to solidify, action star Michael Fassbender became attached to the movie which led to the casting of Dominic West and Olga Kurylenko; Dominic West was approached specifically because of his larger than life presence, needed to fulfill the role of a Roman General, while Olga Kurylenko had recently impressed Marshall with her stunt work as the bond girl for Quantum of Solace (2008) (Eisenberg). With the characters cast, Neil Marshall hired DRS Construction to help build sets designed by Simon Bowles (“Feature Film-Centurion”) and prepared to shoot on location in the Cairngorm Mountains, Badenoch and Strathspey in Scotland, and in Hurtwood Forest, Pinewood Studios, Ealing Studios, and Shepperton Studios in England. To help create the dark and dirty sense of war and to create the feeling of desperation and long odds, the film was shot on location or used practical effects, forgoing the popular use of green screen (“Centurion.” Imdb.com). Director Marshall admitted, “Maybe about 90 percent of the gore effects in it are practical and on-set. Unlike a lot of other directors, I don’t like to leave that stuff until the end of the day, unless I absolutely have to” (Zimmerman). Over 200 liters of fake blood were used during the duration of the shoot (Imdb.com).

Given the green light to begin shooting by its production companies (Pathè Pictures International, the UK Film Council, and Warner Bros.), Centurion was given a $12 million budget (“Centurion.” Imdb.com) and seven weeks to shoot. These constraints are unusual for movies of the sword-and-sandal genre. Normally they are given huge budgets and a long shooting schedule; for example, Gladiator (2001) had a budget of $103 million and was shot over a period of 18 weeks (“Gladiator.” Imdb.com). Zimmerman also states, “for Braveheart, Mel Gibson had six weeks to shoot one battle. We had seven weeks to shoot our entire film. We had like three days to shoot our big battle.”

Finally, to tie everything together, Ilan Eshkeri was hired to produce the soundtrack. Before writing the music, Eshkeri spent time listening to Celtic folk music from all over northern Britain, and drew on it heavily as his influence, even going as far as incorporating Scottish instruments such as the carnyx and the bodhràn. To produce the music, he had the London Metropolitan Orchestra record at Abbey Road Studios (“Centurion”). This combination creates a full epic sound very typical of films in the sword-and-sandal genre.

THEMES AND INTERPRETATIONS

Even though in other aspects of the film, director Neil Marshall went out of his way to set Centurion apart from other sword-and-sandals action movies, thematically it is very generic with one exception. Like many other sword-and-sandals movies the first major theme of the film is that of one’s duty to others and personal honor. Honor is defined by commitment to a cause and keeping one’s word, while duty is carrying out one’s word. It is this simple idea that drives the plot forward. After the massacre of the Ninth, Quintus Dias convinces the survivors to travel north to save the general because it is their duty to the legion and to Rome to try to rescue the General (Centurion 28:40). Later, when the fugitives are on the run due to their failed rescue attempt, Dias remembers his father’s words that honor and duty is what sets man apart from a beast (Centurion 51:00-52:00). This idea can be readily seen in the movie The Eagle, which is also about the disappearance of the Ninth Legion. In The Eagle (2011), the main character Marcus Aquila (Channing Tatum), crosses into the north to reclaim the standard of the Ninth legion and restore his family’s honor, which was damaged when his father lost the eagle. The idea of honor is possibly such a common trope for these types of movies because it is a way to legitimize violence. Violence is brutal and ugly, inflicting terrible emotional and psychological damage. Sword-and-sandal movies feed off this violence, but if the movie cannot justify it, the audience will reject it. Therefore, having characters fight to restore their family, to protect their families, or to right an injustice causes the audience to sympathize with the hero, giving the directors the ability to drive the story through violence.

The other major theme of Centurion is the idea that there is no such thing as a black-and white-war; it is always shades of gray. The two main sides in the movie are the invading Romans and the raiding Picts. The story is told from the Roman perspective; from this perspective the Picts are the enemy and they are savage, uncivilized barbarians who threaten civilized society. In truth, the Picts are justified in defending their homeland, though they are not portrayed as all good either since they pillage and kill innocents at will. Neil Marshall feels “that war is not as cut and dry as good guys and bad guys. There are heroes and villains on both sides. Both sides are capable of that kind of brutality” (Zimmerman). This is seen in the main protagonist of the film, Quintus Dias. Though he is part of the invading army, he is fighting not because he enjoys killing Picts, but to protect the settlements south of his posts. He is a man who is driven by the need to do his duty and defend his friends. In essence the film is about a man trying to survive in a world of with no clear right or wrong choices.

A unique trait of Centurion is its theme of women being both powerful adversaries and saviors. Normally, in sword-and-sandal movies, women play a secondary role—supporting men, defending a man, or plotting behind the scenes. For example, Varinia in Spartacus (1960) is there to motivate and validate Spartacus and to look pretty, but little else. Queen Gorgo in 300 (2006), is the rare exception of a strong-willed woman in this type of movie, but even she only factors into the plot on occasion, and only to defend Leonidas’s beliefs when he is gone. The two female characters in Centurion defy this established role for women in sword-and-sandal movies. Etain is a warrior greater than many men with skills unmatched by others. She has the ability to lead men unquestioned (Centurion 1:17:10-1:24:40). Arriane on the other hand is able to live alone, takes care of herself, stands her ground against a hunting party, and acts as a savior to Dias and his remaining friends (Centurion 1:04:04-1:16:30). This stylistic change is partially a reflection of the modern times, as well as a representation of a society (Picts/Caledones) that values women more than is normal in these epics.

Another way this film breaks the mold of typical sword-and-sandal movies is in its color scheme. “The director of photography, Sam McCurdy, and I discussed it for a long, long time. We wanted this to be a cold movie. We filmed it in cold conditions and it’s a very cold movie as part of being the flipside of what everybody expects in a sword-and-sandals film. When I think of sword-and-sandals movies, I’m thinking deserts and the Middle East and sun and dust and all that kind of stuff. With this one, it’s like, ‘Yes, it is a sword-and-sandals movie. Yes, it’s about the Romans, but it’s in their farthest, grimmest, coldest, wettest frontier. It has to have a totally different feel about it.’ And so we wanted it to have this steely blue feel to the whole thing and make the audience sense what they were going through; the shivers and the chattering teeth and breath, that’s all real as we filmed it in subzero temperatures. In order to help the audience really sense that, we gave just a little of a blue tint to it. It just makes it feel a little colder” (Zimmerman). This cold and icy feel fits into the horror elements incorporated into the film. The horror aspects of gore and an almost supernatural stalker help to heighten the sense of peril, and futileness of the fugitives in the vast wilderness of the north.

CONCLUSION

In comparison to other sword-and-sandal movies, Centurion both succeeds and fails. There is no denying that it has a thin plot that hinges on roughly only two points (the massacre of the Ninth and surviving behind enemy lines), and it pales in this regard next to the greats of the genre like Gladiator or Spartacus; but, it is on par with is close counterpart The Eagle. The other major failing of the movie is its characterization or lack thereof. Other than Quintus Dias and Thax, it is easy to mix-up the other remaining characters. If the characters were left nameless, it would change little to the story. In a way this is akin to the horrendous King Arthur (2004), in which the knights are named but if someone switched their names or changed them completely it would do nothing to the story. These failures lead to a lack of depth in the movie, but it does not greatly affect it because the film does not try make its audience believe it is deep. The movie’s intention is to tell the story of what happened to the Ninth Legion, and why they disappeared from the records; the characters are there to facilitate this and nothing more.

Centurion’s successes, I feel, far outweigh these failures. The film does a great job presenting through its large, cold, and gorgeous vistas of mountainous crags and never ending forest, the desperation of soldiers behind enemy lines in an unknown land. It also succeeds in giving a satisfying explanation as to why the Ninth Legion disappears from the records by making it the result of a cover-up by corrupt politicians. My favorite parts of the movie, though were the fight sequences with their practical effects. The gore is at times over the top, but it helps the audience really feel the utter horror of being in the middle of a battle in hand-to-hand combat. Finally, this movie deserves a lot of respect for accomplishing all of this on a budget almost unheard of for action-adventure epics, with a shockingly short filming schedule.

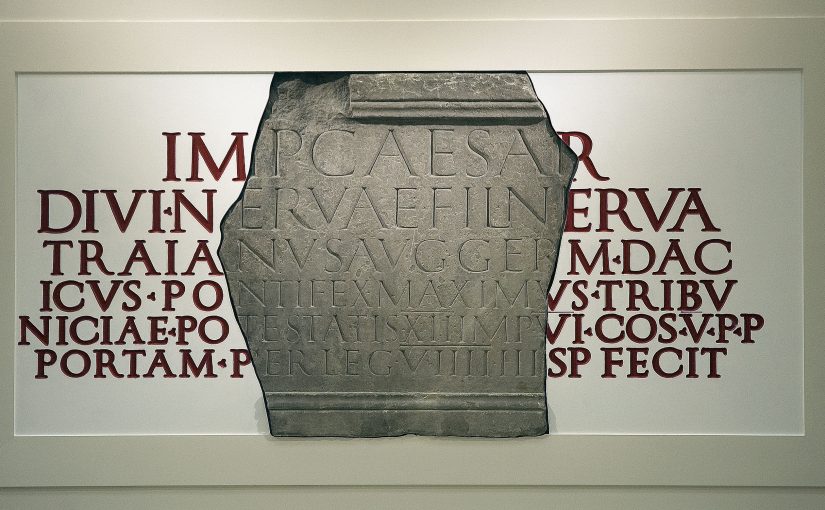

(Header Image: A stone inscription from York referencing the Legio IX Hispania, 108 AD. Photograph by: York Museums Trust Staff. York Museums Trust. Licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.)

Works Cited

Centurion. Dir. Neil Marshall. Perf. Michael Fassbender, Dominic West, and Olga Kueylenko. Warner Bros., 2010. Film.

“Centurion (Ilan Eshkeri).” MovieScoreMedia.com. MovieScore Media Sweden. Web. Accessed 3 May 2016.

“Centurion.” Imdb.com. Amazon.com Company. Web. 3 May 2016.

“Centurion- Neil Marshall Interview.” IndieLondon.co.uk. IndieLongdon.co.uk. Web. 3 May 2016.

The Eagle. Dir. Kevin Macdonald. Perf. Channing Tatum, Jamie Bell, and Donald Sutherland. Focus Feature, 2011. Film

Eisenberg, Mike. “Interview With ‘Centrion’ Director Neil Marshall & Axelle Carolyn.” Screenrant.com. Screen Rant. 22 August 2010. Web. Accessed 3 May 2016.

Everitt, Anthony. Hadrian and the Triumph of Rome. New York: Random House Publishing. 2009. Print.

“Feature films- Centurion.” DRSConstruction.co.uk. DRS Construction. 2015. Web. Accessed 3 May 2016.

“Gladiator.” Imdb.com. Amazon.com Company. Web. Accessed 3 May 2016.

Holden, Stephen. “Two Vastly Different Enemies share a Common Thirst for Blood.” NYTimes.com. The New York Times. 26 August 2010. Web. Accessed 3 May 2016.

Lendering, Jona. “Legio VIIII Hispana.” Livius.org. Livius.org. 5 August 2015. Web. Accessed 3 May 2016.

Manea, Irina-Maria. “The Enigma of the Ninth Legion.” Historia.ro. Adevărul Holding, 2014. Web. Accessed 3 May 2016.

Russel, Dr. Miles. “The Roman Ninth Legion’s mysterious loss.” Bbc.com. BBC. 16 March 2011. Web. Accessed 3 May 2016.

Tacitus. Agricola. Trans. A.R. Birley. New York: Oxford University Press, Inc., 1999. Print.

Tunzelmann, Alex von. “Centurion has a familiar ring about it, but it’s not because it sticks to the facts.” TheGuardian.com. Guardian News and Media Limited. 19 April 2012. Web. Accessed 3 May 2016.

Zimmerman, Samuel. “Fangoria Interview: ‘Centurion’: Marshall-ing Forces.” MichaelFassbender.org. MichaelFassbender.org. 27 August 2010. Web. Accessed 3 May 2016.

Hollywood and History is an on-going series featuring the original work of students in the course Ancient Worlds on Film. Papers have been slightly edited for publication.