In The Discovery of Global Warming, Spencer R. Weart tells the story of the few dedicated scientists who first detected and questioned a change in climate through to the growing public awareness of warming in recent decades. Several major contributors are mentioned from Stewart Callendar, John Tyndall, and Thomas Chamberlin who first got the ball rolling, to major figures in more recent society such as James Hansen. Weart sets a heavy focus on the difficulties that arose at each step along the way; the lack of research funding, the miscommunication among scientists in early decades, the uncertainty of General Circulation Models (GCMs), ect.

With all of this information given, what I found most interesting about Weart’s work was his minimal but strikingly beneficial use of climate metaphors. The following metaphor sparked my interest, “If an inspector tells you that he has found termites in your house, and some day your roof will fall in, you would be a fool not to act at once” (Weart viii). This is way of saying the evidence is there that our climate is changing but the majority of people today are fools for not acting quickly.

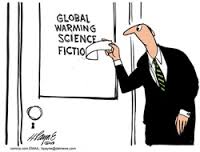

Metaphors in scientific writing and news stories may often be avoided because they might create a lack of rationality. However, after further exploring some well-known climate metaphors it became clear to me that they have the potential to be an extremely powerful and fascinating form of communication. The following are two metaphors that I came across that really impressed me.

“The world we know is like the Titanic. It is grand, chic, high-powered, and it slips effortless through a frigid sea of icebergs. It does not have enough lifeboats… If we do not change course, disaster, perhaps catastrophe, is almost inevitable” John Brandenburg, Dead Mars, Dying Earth

“The currents of change are so powerful that some have long since taken their oars out of the water, having decided that it is better to surrender, enjoy the ride, and hope for the best—even as those currents sweep us along faster and faster toward the rapids ahead that are roaring so deafeningly we can hardly hear ourselves. “Rapids?” they shout above the din. “What rapids? Don’t be ridiculous; there are no rapids. Everything is fine!” There is anger in the shouting, and some who are intimidated by the anger learn never to mention the topic that triggers it. They are browbeaten into keeping the peace by avoiding any mention of the forbidden subject.” – Al Gore, Six Drivers of the Future

Check out the link below to see other popular climate metaphors and discussions regarding this indirect form of communication.