Last night I was fortunate enough to attend a cocktail reception hosted by the United Nations Foundation and Deutsche Bank. A Dickinson College senior from Stroudsburg, PA, I was sipping champagne with a former US Senator, international business executives, and other “high level” leaders in a beautiful Danish palace. Bill Clinton even made a special satellite appearance. I hardly knew anyone, but found that engaging in conversations with these intimidating strangers was relatively easy. We all had one common bond—- our concern for our climate. Though the reception was fabulous and luxurious, I just realized that I am most thankful for the opportunity I had to speak with Professor Michael Gerrard, from Columbia University’s School of Law.

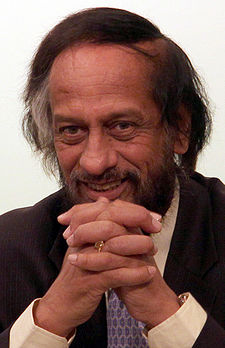

A bit of context information is important to understand why I place such value on last evening’s encounter with Professor Gerrard. This morning, the Dickinson delegation had the good fortune to eat breakfast with Dr. Rajendra Pachauri, the Chair of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Though I was not fully caffeinated, I managed to ask Dr. Pachauri one coherent question that has been on my mind since I arrived at Cop-15:

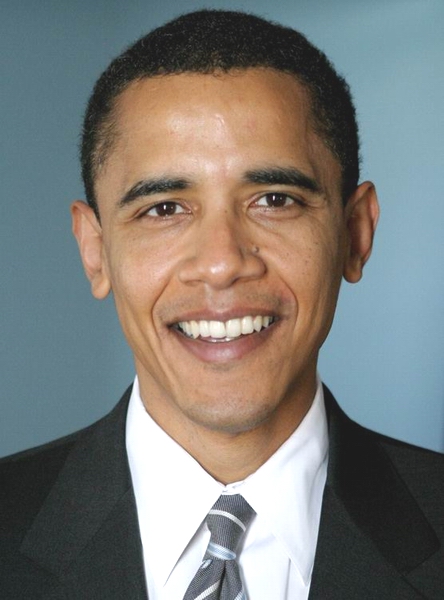

“Many American citizens are dissapointed with the Obama Administration’s weak stance on global climate change policy. In the several years since we failed to ratify Kyoto, there has been a political ‘voter revolution’ which allowed us to elect President Obama. By electing Obama, we thought we were electing a progressive president who would have progressive climate policies. Instead, we are still holding the rest of the world back (in a way). What should we do now?”

Dr. Pauchari quickly answered that Americans place too much emphasis on the capabilities of Congress, and not enough on President Obama’s executive authority. He mentioned that he thought President Obama had the ability to execute his own power to engage the US in global climate treaties, rather than waiting for approval from Congress. Doing this would have two effects: 1) it would send a clear message to Congress that they need to get on board and 2) it would send a clear message to the world community that the US is on board with negotiations. This was the first time I even heard this suggestion that we take the emphasis off legislative power and place more power in the hands of the executive. Instantly I felt like the whole paradigm through which I viewed this political issue shifted.

Today I started Googling to find out more. Was Dr. Pauchari the only leader who suggests such a paradigm and policy shift of focus for US policy? I quickly realized, he was not. In fact, Professor Gerrard, my new acquaintance from Columbia, is a leading scholar on this exact issue. Apparently Professor Gerrard has just published a working paper which, according to blogger David Sassoon, studies the:

“legal basis of the president’s independent power to enter into internationally binding commitments related to climate change, and it finds that the president has broader powers than commonly recognized. It also identifies an intriguing possibility backed by historical and legal precedent.”

I need to read Professor Gerrard’s working paper before I draw any conclusions, but putting all of these connections together, and hearing new viewpoints gives me a little more hope for the state of US climate change policy.

Including REDD (Reductions of Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation) within the post-2012 agreements is an incredibly important choice that faces UN delegates. The Bali Climate Action Plan provided a roadmap which included emissions from land use, land use change and forestry (LULCUF) within the agreement. This has been a particularly devisive issue within the conference, because it impacts many constituencies and is poorly defined. There is a need for the language within the post 2012 agreements to effectively provision for carbon sequestration, biodiversity, governance, and indigenous rights. Sequestering carbon is the primary objective for REDD projects. However, managers of initial pilot projects around the world suggested that biodiversity, governance, and particularly indigenous rights need improvement. The cartoon below depicts some of the potential problems.

There are numerous social activists who have come to the conference to voice their opinions about how indigenous rights should be strengthened within REDD programs. Several Side Events within the conference have included indigenous people on the panels. For example, one side event had an indigenous activist from Panama who claimed that REDD was a farce. He like many others hold this view, because the economic incentives that are promised for protecting forests never end up helping the local people. He has developed an international network with other indigenous leaders and has consistently found that indigenous peoples were not given proper input into REDD projects. Existing forestry management practices often already acknowledge the right of indigenous people to have rights. In Panama 34% of the forests are set aside as indigenous land. However, on the ground indigenous peoples are often manipulated and do not have the right of free an informed consent. REDD programs can sometimes be seen as an act of neo-colonialism, because the forest land is taken away from indigenous peoples to guarantee carbon offsets for developed countries. Therefore, REDD programs should be established as a way for people from developed nations to fund better management practices within developing nations.

Economic as well as moral considerations need to be evaluated for REDD projects. Often the unique life style and culture of indigenous people make it difficult for them to adapt to mainstream forms of life. The implementation of these projects should help to incentivize sustainable management of the forests, while ensuring that indigenous people are not suppressed by these measures. One way to help indigenous people economically is to set up profit sharing programs, where the local people benefit from deforestation prevention. This was exemplified in the JUMA project that was mentioned in . Ultimately, there is a need for REDD projects to include sustainable development and provisions to ensure indigenous rights.

Tags: LULUCF, Philip Rothrock, REDD, sustainable development

In the ten or so days that I’ve been attending the COP and related events, I have been given two t-shirts, one water bottle, one bag, a raincoat, a handful of postcards and several buttons that mark me as a supporter of different climate-related causes. (It should be noted that most of these objects will go largely unused after the COP is over.) When comparing my booty with those of other members of my delegation, I realized I was way at the lower end of acquisition, with most of them having received many more items. After overcoming my first reaction – I want those things too! – I realized that even the most committed climate change activists are getting the picture at least partially wrong.

In the ten or so days that I’ve been attending the COP and related events, I have been given two t-shirts, one water bottle, one bag, a raincoat, a handful of postcards and several buttons that mark me as a supporter of different climate-related causes. (It should be noted that most of these objects will go largely unused after the COP is over.) When comparing my booty with those of other members of my delegation, I realized I was way at the lower end of acquisition, with most of them having received many more items. After overcoming my first reaction – I want those things too! – I realized that even the most committed climate change activists are getting the picture at least partially wrong.

Consumption is one of the main drivers of climate change, and it works by coupling individual identity with acquisition of commodities. As the climate Ambassador from South Korea was explaining at a side event on sustainable transportation, in traditionally bike-riding Asian cultures, driving cars has now become a symbol of richness. This example is only one of the many discussed by the literature on the sociology of consumption. We acquire things because they will signal to other people that we can afford them, and that we have the cultural capital to understand and embrace them.

The road to climate change mitigation marks the need for curbing consumption, in particular in the developed world. Consumption reduction not only helps reduce the amount of resources extracted from the Earth and the energy that goes into the manufacturing process, but it also creates a space in which individual lives are less commodified and more open to human interaction. An improvement in public welfare is at the heart of this issue: things can’t make us happy, but relationships might. And in building closer connections, we may be able to communicate our individualities in ways other than the objects we possess.

So here my question is raised: is it possible for active climate change organizations, which spearhead the fight for mitigation and adaptation, to set the example on how a sustainable world would function? Activism is vital in the road to sustainability, and the work done so far has been excellent, but it is far from over. All of us should be paying a little less attention to the color of our shirts, and a little more to the relationships we create along the way.

Dave Munn and I spend the morning at Kilmaforum2009 which is also known as the people’s summit. The Kilmaforum is a parallel conference to the COP15 organized by a broad coalition of Danish and international environmental movements and civil society organizations. Although not part of the official COP, this event has drawn a wide and impressive array of highly influential individuals and organizations including Vandana Shiva, Bill McKibben, Naomi Klein, Wangari Maathai, Mohamed Nasheed and Sister Jayanti. Today was the second day I’ve visited the Klimaforum and I am continually impressed at the number of UNFCCC official badges I’ve see tucked around people’s necks, and the frequency at which the color at the base of their tags is pink, indicating their status as an official delegate. The importance of this conference might be often overlooked, but the extent of it’s influence is something for all to think about.

Dave Munn and I spend the morning at Kilmaforum2009 which is also known as the people’s summit. The Kilmaforum is a parallel conference to the COP15 organized by a broad coalition of Danish and international environmental movements and civil society organizations. Although not part of the official COP, this event has drawn a wide and impressive array of highly influential individuals and organizations including Vandana Shiva, Bill McKibben, Naomi Klein, Wangari Maathai, Mohamed Nasheed and Sister Jayanti. Today was the second day I’ve visited the Klimaforum and I am continually impressed at the number of UNFCCC official badges I’ve see tucked around people’s necks, and the frequency at which the color at the base of their tags is pink, indicating their status as an official delegate. The importance of this conference might be often overlooked, but the extent of it’s influence is something for all to think about.

The question of this morning’s discussion was will a Global Green New Deal save us? Two men from Attac German, presented some of the policy changes suggested under the Green New Deal economic stance. The presentation itself was interesting, but to both Dave and I, the responses from the audience gave this session depth. It re-sparked this dilemma that I’ve been struggling with for some time. Which is better: quick, bold action that is potentially poorly designed and could cause severe consequences or taking a bit more time to develop a well thought out, intentionally designed effective system of change that can be tweaked to be most effective.

This dilemma is present throughout the negotiations; should we include a REDD (reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation) program with loopholes that allow for leakage? should a Global Green Economy be created even if it is still based on the capitalist growth and debt imperative? Should the 17 of us have flown over here for two weeks even though it’s been proven that air travel is hugely destructive? Could we have made an equal if not more meaningful impact at home or in Carlisle? Should any country, any individual, agree to emissions targets that perpetuate social, environmental, economic or climate injustices? Climate change is an urgent problem, however can it claim any more urgency that the Afghanistan War, the lack of water in India, food scarcity in Africa, or the displacement of thousands of people in Bangladesh or the Southern Coast of the United States?

This morning on commenter referred to climate change as an acute problem. Other problems, specifically capitalism, are chronic problems. He asked how we could talk about capitalism when climate change is leaning over us like a falling redwood tree. How can we talk about changing fundamentals when a problem of this magnitude has been identified…why are we discussing other things? I understand this viewpoint; the science is pretty clear that unless we stabilize our green house gas emissions below 350 ppm, we will be facing massive, unpredictable changes in Earth systems. So in response to this argument, yes strong action is required from every point on this planet.We need to set bold emission reductions targets immediately.

However, if we choose to establish clean coal technology, drill for natural gas, build nuclear power plants, engage in “sustainable” mono crop plantation forestry, convert deserts into massive wind and solar farms and genetically modify our food stocks, what will the world look like in 50 years? Our green house gas emissions may have decreased, but probably not to the extent they need to, and we will have exploited much, much more of the Earth than we already have today. What are we willing to give up to perpetuate these systems that are not working? Viable soils, clean waters, health of millions of people, social justice… are we willing to give these up for cheap energy and greed?

I dunno. I don’t have an answer.

Tags: adaptation, bill mckibben, climate change, Danielle Hoffman, developing countries, global green new deal, klimaforum2009

The principle of common but differentiated responsibilities boils down to which countries should spend on climate finance and how much they should spend. As a whole, the global community has spent no where near the level it should be spending on adaptation and mitigation.

Estimated yearly adaptation cost is US$8 billion to US$100 billion per year by 2030. Within the same time frame, mitigation cost is about US$650 billion a year (IIED briefing: Billions at stake in climate finance). Those numbers, high as they seem, recently have been considered underestimation. In contrast, the total committed fund since 2002 under the Kyoto Protocol is just over US$18 billion, out of which only US$1 billion has been disbursed. That is 1/750 of what is needed per year. With all the news about advancement in climate finance, and all the discussion going on at COP15 about this topic, the statistic is simply unbelievable.

Sources of funding for climate finance include: public finance, private finance and international funds (including Adaptation fund, other UNFCCC funds, GEF fund, etc.). International funds come mainly from committed fund from wealthy countries. As a result, public finance and private finance take most of the responsibilities for meeting financing needs. If wealthy countries contribute 0.5 to 1% of their GDPs, the sum would be US$200 billion o US$400 billion. Private sector has even more resources to invest in climate-related projects.

With the current stage of development, even if any commitment is made at COP15, climate finance as a sector has a long way to go before it can meet global demand for funding of adaptation and mitigation. A few questions remain: Will wealthy countries be willing to commit 1% of their GDP? Will the climate finance products innovate fast enough? Do receiving countries have the capacity to absorb the massive funding and make good use of it?

Tags: adaptation, Adaptation Fund, Climate Finance, COP15 Resources, Financing, GEF, Luan Nguyen, mitigation

Your Comments