When I hear the term “soul food”, my mind goes straight back to my trip to New Orleans over the summer. Restaurants advertised these warm, flavorful, American classic foods, and the lines for some places were out the door and down the block. I remember those specific smells and tastes; the fried okra, the fried chicken, the seafood gumbo with so many delicious spices. These are all foods that I associate with the American South, only to find out from today’s guest lecturer that the history of these dishes is much richer than I had ever imagined. Professor Lynn Johnson taught our class about the extensive history of soul food in America and how it grew from unwanted food to comfort food.

“My Aunt Jojo’s Seafood & Vegetable Gumbo”. Photo Courtesy of Lannen Lare.

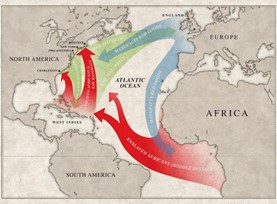

Little did I know that the origins of foods that I saw as American classics really came from Africa, dating all the way back to the Transatlantic slave trade. Slaves brought their foodways to America along the Middle Passage (Hayford, 2018). They were expected to make food and sustain themselves from the leftovers of white slave owners, and these weren’t nice leftovers like you and I eat after Thanksgiving! The rejected food would be tossed down to them, and they were forced to try and make something palatable and nutritious to eat (L. Johnson, personal communication, October 29, 2024). African Americans had to draw from their experiences in African food markets and settings, bringing their cultural foodways to their new environment and starting a new, unique era of food there (Opie, 2008). Like I said earlier, the soul food that I have eaten is easily accessible to me in my memory. Food, especially soul food, truly has the ability to invoke such vivid, sensory memories, and it has the ability to connect people through this concept. This comes from the influence of African food markets and their exchanges of taste, smell, sight, and more (L. Johnson, personal communication, October 29, 2024). Soul food provides us with more than sustenance: it gives us an experience to share.

https://www.nps.gov/articles/the-middle-passage.htm

https://www.aaihs.org/cfp-revolutionary-soul-food/

One point that stuck out to me especially was how soul food rose from the instinct to survive. Slaves used their knowledge to supplement their diets when slave owners did not give them sufficient food rations, and even post-abolition of slavery, African Americans started food stands, restaurants, and hotels to spread their food culture and make money to live during the Great Migration (Worley, 2019). Soul food was and is much more than a foodway; it’s about ownership and empowerment. African Americans were doing something for themselves and gaining this sense of agency by just taking control and sharing their knowledge and their value with the world. Soul food became something that Americans of any race treasured and desired, and it will continue to live on through experiential wisdom (L. Johnson, personal communication, October 29, 2024). I know that I personally will be seeking out more from my food in the future. It’s not just about the eating, but the community, shared experience, and connection of humankind that soul food fosters in such a unique way. Our bodies need food, so why not feed the soul, and make a little connection go a long way?

https://restaurant-ingthroughhistory.com/2019/03/24/soul-food-restaurants/

https://www.stoptheviolencepgh.com/a-soulful-taste-of-the-burgh/

References

Hayford, V. (2021, June 3). The humble history of soul food • black foodie. BLACK FOODIE. https://www.blackfoodie.co/the-humble-history-of-soul-food/

Opie, F. D. (2008). Hog & Hominy: Soul Food from Africa to America. Columbia University Press.

Worley, S. (2016, June 29). Where soul food really comes from. Epicurious. https://www.epicurious.com/expert-advice/real-history-of-soul-food-article

Halpin, J. (2024) Dickinson College Farm

Halpin, J. (2024) Dickinson College Farm