By Matthew Ferry

John Ferry was ten-years old when he left his mother’s West Philadelphia home in 1961. That year, he began studying at Girard College–a boarding school endowed by the will of Stephen Girard, and established as an institution for “poor, white, male orphans.” [1] The forty-three acre property surrounded by a ten-foot tall wall was established in North Philadelphia, a neighborhood that became predominately African-American during the 1940s and 1950s as whites left for the suburbs. [2] H.W. Brands described the inner city as a place where “blacks lived in substandard housing, attended substandard schools, and worked at substandard wages.” [3] For residents of North Philadelphia, Girard’s wall was a symbol of exclusion, inequality, and racism. Behind these walls Ferry spent eight years of his life until he graduated in the spring of 1969. Reflecting on his youth and the city’s struggles to integrate, Ferry vividly recalls how West Philadelphia changed from when he “was born–from all white, to all black,” and the gang violence and protests that were prevalent just beyond Girard’s wall. He also recalls when times were different. Ferry fondly remembers hot summer nights in West Philadelphia when “all the families [in the neighborhood] would sleep outside on their front porches.” [4] Ferry’s recollection reveals how Philadelphia struggled to integrate and the implications that white’s resistance to reform had for race-relations.

The rise of mass suburbs in the 1950s proved a haven for white residents who sought to escape the crowding, conditions, and cultural differences that were prevalent in the city. World War II left Philadelphia with a massive housing shortage. Over seventy-thousand houses in the city lacked a bath or were run-down, and roughly fifty percent of homes were built in the nineteenth century. [5] The Philadelphia Housing Authority attempted to improve living conditions and spearhead integration by developing high-rise public housing projects in white communities. However, residents were resistant to the introduction of poor African-Americans in their neighborhoods. The Authority could not address the demand for affordable housing or accommodate the thousands of families displaced in the city. [6] Outside of Philadelphia, thirty-six new homes were being erected daily–fitted with two bedrooms, one bathroom, a living room, and a kitchen. Known as the Levitt model, these homes sold for $7,990 and were an attractive option for former GIs or middle-class families eligible for low interest rate federal loans. [7] Irish and Ukrainian residents of North Philadelphia moved to the suburbs as blacks moved in. Similar patterns emerged in Ferry’s West Philadelphia neighborhood. As whites left the city for suburbia, blacks came to occupy the homes that were the oldest and hardest to maintain, and their high rents and mortgages provided only the worst shelter. [8]

Police activity during the Columbia Avenue riots. Courtesy of Temple University Libraries, Urban Archives.

For African American communities across the city, the North Philadelphia, Columbia Avenue riots of August 1964 instilled a new spirit of militancy and determination to challenge the pace and goals of integration. During the 1960s, around half of Philadelphia’s five-hundred and thirty-thousand African Americans lived in North Philadelphia. Residents typically only completed eight years of school and the average income was thirty percent below the city. [9] As civil rights leaders failed to address these inequalities tensions built across the city. Black’s frustration with their circumstances erupted on August 28, 1964, when a rumor circulated that police had killed a pregnant black woman on Columbia Avenue. [10] Thousands of residents took to the streets, clashed with police, broke storefronts, and looted. Rioters dramatically outnumbered the police patrolling the area, and the city deployed fifteen hundred policemen to control the crowds. Philadelphia NAACP President Cecil B. Moore and other civil rights leaders pleaded to the crowd to stop but were dismissed. To Moore’s requests, one woman responded “this is the only time in my life I’ve got a chance to get these things,” signifying that the absence of progress and circumstances blacks faced provoked the riots. [11] In the end the riots lasted three days and left two people dead, three-hundred and thirty-nine injured, and nearly three million dollars in property destroyed. [12] The Columbia Avenue riots demonstrated the frustration of African Americans with the white establishment and their desire to establish for themselves the pace and aim of integration.

Seven months after the riots, Cecil B. Moore promised to “rededicate Philadelphia’s civil rights campaigns to improving the conditions of African-Americans.” [13] Moore directed his attention to Girard College. The school’s entirely white study body and ten-foot high walls–located in the midst of North Philadelphia, were symbols of the city’s failure to address the needs of poor and working-class blacks. On May 1, 1965, the NAACP protest against Girard began with twenty demonstrators and eight-hundred police officers. The picketers demonstrated outside of Girard day and night for seven months, and the size and intensity of the crowd grew over time. Ferry recalls how teachers at Girard told him that protestors would scale the wall at night and kill him in his sleep. [14] One of the most powerful moments of the demonstrations occurred on August 3, 1965, when Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. addressed a crowd of five-thousand protestors outside of Girard’s walls. Dr. King told the crowd that Girard and its walls were “symbolic of a cancer in the body politic that must be removed before there will be freedom and democracy in this country.” [15] The Reverend reminded the demonstrators to neither fault nor wane in their efforts to reform an institution symbolic “of the rejection and deprivation inflicted on the Negro people.” [16]

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. attends rally at Girard College. Courtesy of Temple University Libraries, Urban Archives.

Moore’s campaign to integrate Girard College forced Philadelphia to realize its own dark history of discrimination and segregation at the same time the nation celebrated the end of enforced segregation in the South. While Girard’s trustees refused to concede to protestors demands, trustees President John A. Diemand met with Governor William Scranton and May James James Tate in July of 1965 to discuss legal and judicial solutions to Girard’s racial ban. In December 1965, city and state officials filed suit in United States District Court, and Moore postponed the NAACP protest campaigns against Girard College. The case moved through the court system and in March of 1968, the U.S. Court of Appeal for the Third Circuit ruled that Girard had violated the constitutional rights of seven African American applicants by refusing them admission. Girard’s board of Trustees appealed this decision to the U.S. Supreme Court, which declined to hear an appeal of the lower court ruling. [17] In the fall of 1968, four African American boys entered Girard. However, integration did not mean the school’s white students were welcoming of their new, non-white classmates. The first African American graduate of Girard, Charles Hicks, recalled how a classmate regularly threatened to kill him in his sleep. [18]

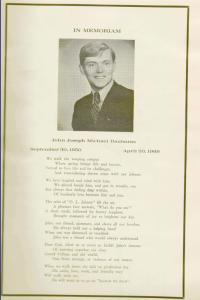

As African American communities grew agitated with the pace of progress made through nonviolent demonstrations, black youths felt compelled to take their grievances to the streets. For North Philadelphia youths in particular, their aggression was directed to the well dressed and well groomed students behind Girard’s walls–the epitome of everything the white establishment prevented blacks from being. Whenever Ferry stepped outside of Girard’s main gate he ran the risk of being attacked by local boys affiliated with a gang called the Moroccos. When a Girard College student ventured beyond the wall, there was no assurance of their safety. Even at church one Sunday, Ferry and his classmates were involved in a physical altercation against black youths. Forty-one Philadelphians were killed in gang-related conflicts in 1969. [19] That year Girard student John Daubaras was shot to death right outside of Girard’s walls in front of his two sisters and two friends. Daubaras’ death deeply shocked his classmates. Some Girard students left the school armed the day of his slaying, seeking revenge for their fallen friend. [20] Integration did not resolve relations between Girard’s white student body and North Philadelphia’s black residents. The long drawn court battles had left both North Philadelphia residents and Girard’s students resistant to cohesion beyond that required of the law. The tragic killing of Daubaras signified that North Philadelphia’s disdain towards Girard College and its white community had reach its zenith.

In the Girard College yearbook for the 1968-1969 school year, a poem written by a member of the school community is dedicated to the life of John Daubaras. In its penultimate stanza, the author wrote “Dear God, allow us to strive to fulfill John’s dreams; Of knitting together our class, Girard College and the world, Free from revenge, or violence of any means.” [21] John’s dream–his vision for the world–was exactly what civil rights leaders across the nation fought for; a world where individuals, regardless of skin color, could come together and coalesce as a single community. White communities across Philadelphia and the nation resisted efforts to integrate their neighborhoods, schools, and the workplace. The social-mobility and opportunities found in white society were lawfully denied to African Americans, who were restricted to substandard conditions. The concessions blacks gained through the courts and legislation put an end to de jure segregation and other forms of institutional discrimination. However, Institutional racism while no longer lawful, has continued to exist in every facet of society. Through reflecting on the battles won and loss during the Civil Rights Movement, it is possible to see both how far we have come and where we need to go. In better understanding the progress that has yet to be made, we may one day make Daubaras’ dream for our world a reality.

[1] “Supreme Court upholds admission of Negros to Girard College,” Observer-Reporter, 21 May 1968.

[2] Russell F. Weigley, eds, Philadelphia: A 300-Year History, (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1982), 669.

[3] H.W. Brands, American Dreams: The United States Since 1945 (New York: Penguin Books, 2010), 148.

[4] Interview with John Ferry, Philadelphia, PA, March, 14, 2015.

[5] Weigley, Philadelphia: A 300-Year History, 669.

[6] Jon C. Teaford, Review of “Public Housing, Race, and Renewal: Urban Planning in Philadelphia, 1920-1974,” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography

Vol. 113, No. 1 (Jan., 1989), 97 [JSTOR].

[7] H.W. Brands, American Dreams: The United States Since 1945, 78.

[8] Weigley, Philadelphia: A 300-Year History, 669.

[9] Sara A. Borden, “Columbia Avenue,” Civil Rights in a Northern City: Philadelphia, accessed April 28, 2015, <http://northerncity.library.temple.edu/people-and-places/columbia-avenue?civil_rights_popup=true>

[10] Matthew J. Countryman, “Why Philadelphia,” Civil Rights in a Northern City: Philadelphia, accessed April 28, 2015, <http://northerncity.library.temple.edu/content/historical-perspective/why-philadelphia>

[11] Hillary S. Kativa, “The Columbia Avenue Riots (1964),” Civil Rights in a Northern City: Philadelphia, accessed April 28, 2015, <http://northerncity.library.temple.edu/content/collections/columbia-avenue-riots/what-interpretative-essay>

[12] Weigley, Philadelphia: A 300-Year History, 676.

[13] Kativa, “The Columbia Avenue Riots (1964).”

[14] Interview with John Ferry.

[15] Carl E. Sigmond, “Community members campaign for integration of Girard College in Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1965-68,” Global Nonviolent Action Database, accessed April 29, 2015, < http://nvdatabase.swarthmore.edu/content/community-members-campaign-integration-girard-college-philadelphia-pa-usa-1965-68>

[16] John F. Morrison, “Cecil Moore vows to act united with King,” Philadelphia Evening Bulletin, August 2, 1965, George D. McDowell Philadelphia Evening Bulletin Collection, Urban Archives, Temple University Libraries, Philadelphia, PA, accessed April 30, 2015, < http://northerncity.library.temple.edu/content/cecil-moore-vows-act-united-ki>

[17] Carl E. Sigmond, “Community members campaign for integration of Girard College in Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1965-68.”

[18] Juan Williams, “The Gradual Integration of Girard College,” National Public Radio, March, 5, 2005, accessed April 29, 2015, <http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=4786582>

[19] Weigley, Philadelphia: A 300-Year History, 677.

[20] Interview with John Ferry.

[21] “In Memoriam John Joseph Michael Daubaras,” Corinthian (1969), 7.

- Police activity during the Columbia Avenue riots. Photo courtesy of Temple University Libraries, Urban Archives.

- Looting during Columbia Avenue riots. Photo courtesy of Temple University Libraries, Urban Archives.

- Civil rights demonstrators at Girard College. Photo courtesy of Temple University Libraries, Urban Archives

- Civil rights demonstrators at Girard College. Courtesy of Temple University Libraries, Urban Archives.

- Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. attends rally at Girard College. Courtesy of Temple University Libraries, Urban Archives.

Leave a Reply