“We were raised to think that we were that we were the people in the world who were living the right way.”

– Jen Cort, The Farm resident from 1973 to 1984

“’The cultural cliché has it that the flower children danced at Woodstock, crashed at Altamont, and gradually shed their naïve ideals as they made themselves into ice-cream moguls, media magnates, and triangulating politicians,’ Jim Windolf wrote in Vanity Fair in 2007. ‘But the 200 people who live at the Farm,” he added, ‘have managed to hang on to the hippie spirit.’”

-Stephen Gaskin’s Obituary, NYT

The American Yawp textbook calls the 1960s and 70s a time of the counterculture that was defined by “Rock ‘n’ roll, liberalized sexuality, an embrace of diversity, recreational drug use, unalloyed idealism, and pure earnestness.”[1] However, the counterculture was more than just a common group of sentiments and pop-culture items. Many who considered themselves members of the counterculture launched new ventures and made attempts to change the world. One type of attempt at changing the world was the creation of communes. My mother, her siblings, and her stepfathers lived on a commune called The Farm in Summertown, Tennessee.

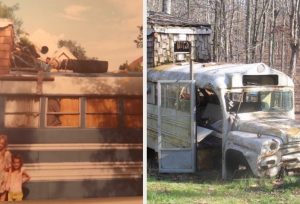

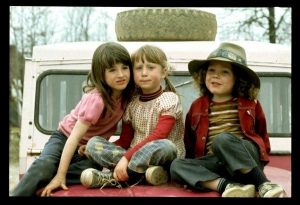

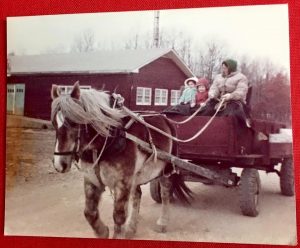

Stephen Gaskin was an English professor turned activist who lectured on the use of psychedelic drugs and world religions. Gaskin amassed a following of roughly 300 people in a caravan of brightly painted school buses and VW vans. The group traveled around the country gaining followers on the way to a 1050-acre farm just south of Nashville. [2] Jen Cort, her mother Carol, and her sister Michelle joined the caravan. “We started our trip from Seattle to Tennessee when I was three and I arrived right after I turned four.” The rolling hills and open fields that later became The Farm were undeveloped, “I lived with my mom, my sister, and my mom’s friend in our bus” with little insulation a small camp stove for cooking and heat.[3]

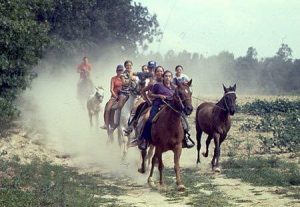

New Farm commits were drawn to the commune for a variety of reasons. “There were a lot of things that went into the decision-making factor. One of the biggest drivers was fleeing the draft, Vietnam. But also, Ina May, who’s considering one of the Mothers of midwifery in this country, she really wanted a place to develop her midwifery practices and Steven, our founder, was her husband.”[4] Though the Vietnam War was coming to a close when Cort arrived at The Farm, anti-war sentiments ran hand-in-hand with an interest in returning to a simpler way of life; “we were creating the ideal life and being very centered on being in touch with nature, working to help people…and very close to the earth.”[5] To ensure proximity to the earth, Farm residents followed a few expectations that fit with the commune’s philosophy; “the Farm’s young men in straw hats and beards and women in long skirts lived an almost puritanical life. They took vows of poverty and pooled their assets. Vegetarianism was mandatory. Mr. Gaskin banned alcohol, tobacco and, to the surprise of many, LSD, though not marijuana. Plenty work — considered a form of meditation — was assigned. Artificial birth control was forbidden.”[6] Future Vice President, Al Gore was friendly with Gaskin and wrote about The Farm for the Tennessean. “Gaskin’s followers eat no meat because they say they have made a ‘spiritual agreement’ with the animals. ‘There would be a lot more vegetarians if everyone had to kill his own meat,’ Gaskin said later.”[7] Gaskin’s followers also participated in the use of drugs and psychedelics, “he admits that his followers smoke it and occasionally do stronger drugs like peyote and psylocybin — or ‘mushrooms’ as they refer to it.”[8]

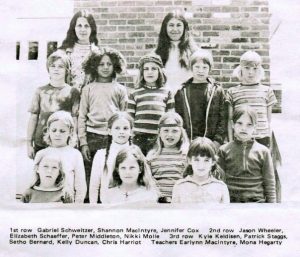

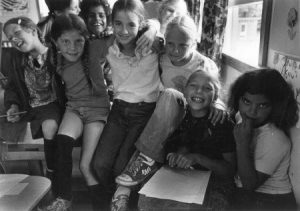

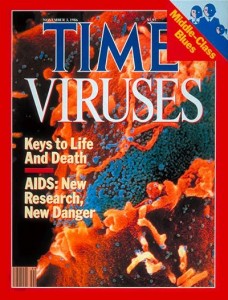

Cort, a child during her time on The Farm, did not participate in the drug use, however, she remembers her time growing up on The Farm as revolutionary and happy, “we always took history from different people’s perspective, like we had Native American history and women’s history…I remember our 5th-grade history class was around socialism and communism and how countries like Russia had done it wrong and failed with communism, but that we were doing it right.”[9] The Farm was a largely idealistic place and was known internationally for its revolutionary ideals. “[Gaskin and The Farm Band] were on the Donahue show…[in] Time magazine, in the New York Times…Globally, they thought that we were doing right…At one point there were famous musicians and scientists, and you know writers who would come and spend time there because we were living in the way that people should live and not being as interested in what they call the material plane meaning physical things. “[10] One famous visitor was the mathematician Buckminster Fuller who was Cort’s math teacher and who she remembers teaching her to use a compass.

Despite idealistic and peaceful appearances, the conservative and rural local community surrounding The Farm did not always appreciate the communes presence. “We had a sign at the end of our road, and we couldn’t have advertisements about where we were because people would want to attack us, throughout my whole childhood people tried to attack us.”[11] In an attempt to protect members of The Farm community and children from aggressive locals, most children weren’t allowed to leave the property unaccompanied and when they did they were buffered by adults speaking to locals for them. At the start of Cort’s freshman year in high school, she decided to secretly attend the public school off The Farm. After she started attending school she was exposed to the full brunt of local criticism, “We were called Devil worshippers, which I didn’t know what that meant but I knew it was bad.” After classmates at her school learned that Cort was living on The Farm, “I lost my status at school. I had sleepovers at my friend’s house all the time and then I couldn’t go to people’s houses after they found out I was from The Farm. I was a cheerleading alternate which at our school was a really big thing but then I was kicked off the team. Teachers started treating me differently because they suddenly knew where I was from. And so, it was very hard.”[12]

Cort says leaving The Farm school to attend a local high school was a contentious decision. After our recorded conversation, Cort explained that Gaskin grew angry with Cort and her mother for deciding to let Cort attend school off The Farm. She said Gaskin was verbally abusive to her. Gaskin’s relationship with Cort and her mother Carol may have also been related to Carol’s role in what is now called “the Changeover.” The Changeover was a moment in which The Farm reached a financial tipping point. The Farm had established many companies including a book-publishing business, a pickle company, a sorghum syrup brand, a Geiger counter-producer,[13] an ice cream company, and a successful midwifery clinic.[14] Despite many business ventures, The Farm was not making enough money to continue to feed the commune’s population or make payments on loans. Cort remembers “we were almost always hungry and cold and without shoes.”[15] As a last effort to keep The Farm economically viable a fellow community member, “Michael and [Cort’s mother Carol] worked together to orchestrate what is commonly referred to as the Changeover…The local bank was saying if you don’t pay back some of these loans, were going to take the land.”[16] Effectively, the 1983 Changeover meant “each adult Farm member was required to contribute financially toward the annual budget and operating expenses for the community.”[17] The Changeover marked a fundamental change in the history of The Farm, “Mom knew, and Michael knew before anyone else that the decisions they were making were going to completely alter the future of The Farm.”[18] The Farm was transformed overnight from a place mostly free of financial obligations in which the essence of the counterculture lived on to an intentional community which maintained some ideals of the old Farm. However, with the reintroduction of money to The Farm, it was nearly unrecognizable. “Nobody had any income like I don’t remember seeing a dollar bill when I was little, I had no idea that…something that was paper could buy me something,” said Cort.[19]

The Farm changed fundamentally after the Changeover and many families who came for the idealistic community that existed before began to leave The Farm. Cort and her family stayed for only a short while later before leaving themselves. By 1983, the Vietnam war had ended eight years previous and the peak of the counterculture movement had ended about a decade before. The Farm was an attempt to prolong and live out the values that anti-war and counterculture movements espoused. The end of The Farm as a commune and its transition into an intentional community was “entirely financial;” most of Gaskin’s and The Farm’s beliefs had remained intact until the very end, proving that intentional living and a radical way of life was possible.

[1] Samuel Abramson et al., “The Sixties,” Samuel Abramson, ed., in The American Yawp, eds. Joseph Locke and Ben Wright (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2018).

[2] “History Timeline.” Accessed May 7, 2021. https://thefarmcommunity.com/history-timeline/.

[3] Phone Interview with Jen Cort, April 29, 2021.

[4] Ibid

[5] Ibid

[6] Martin, Douglas. “Stephen Gaskin, Hippie Who Founded an Enduring Commune, Dies at 79.” The New York Times. The New York Times, July 3, 2014. https://www.nytimes.com/2014/07/03/us/stephen-gaskin-hippie-who-founded-an-enduring-commune-dies-at-79.html.

[7] Gore, Albert. “Church Group Swaps Views with Gaskin.” The Tennessean. March 13, 1972. https://www.tennessean.com/story/news/2014/07/07/from-the-archive-church-group-swaps-views-with-gaskins/12312875/.

[8] Ibid

[9] Phone Interview with Jen Cort, April 29, 2021.

[10] Ibid

[11] Ibid

[12] Ibid

[13] Martin, Douglas. “Stephen Gaskin, Hippie Who Founded an Enduring Commune, Dies at 79.” The New York Times. The New York Times, July 3, 2014. https://www.nytimes.com/2014/07/03/us/stephen-gaskin-hippie-who-founded-an-enduring-commune-dies-at-79.html.

[14] Phone Interview with Jen Cort, April 29, 2021.

[15] Ibid

[16] Ibid

[17] The Changeover. Accessed May 8, 2021. https://thefarmcommunity.com/the-changeover/.

[18] Phone Interview with Jen Cort, April 29, 2021.

[19] Ibid

Phone Interview with Jen Cort, April 29, 2021.

Selected Transcript

Q: How long did you live on the Farm and with who?

A: We started our trip from Seattle to Tennessee when I was three and I arrived either right after I turned 4 or right around that time and we left when I was a junior in high school. And when I went there, I lived with my mom and my sister and my mom’s friend and our bus.

Q: As a kid on the Farm did you think of the Farm as different than the rest of the world?

A: Oh yeah, we were raised to think that we were that we were the people in the world who were living the right planning. But I mean, the world was literally on the farm and off the farm and off the farm. People living on the Farm were people who were living the right way, and everyone off the Farm was living wrong, which was really weird to me because. A lot of my friends didn’t have both their parents on the farm, but I was one of the only ones who saw my dad regularly and I knew he was a good person so I didn’t understand that. But we were absolutely raised that we were the only ones living in the right way.

Q: Did people living on the Farm make it seem like they were there to make an intentional community or were there other intentions for being there?

A: There were a lot of things that went into the decision making factor. One of the biggest drivers was fleeing the draft, Vietnam. But also Aina May, who’s considering one of the Mothers of midwifery in this country, she really wanted a place to develop my midwifery practices and Steven, our founder, was her husband. I know that there was a couple of years where people scouted out land around the country to try to find where we could go live. And then it was supposed to be that we were creating the ideal life and being very centered on being in touch with nature, working to help people, but very much in a white savior way and very close to the earth.

Q: How would people that lived on the Farm describe the Farm when they talked about it?

A: That’s a really good question. And part of why I’m struggling with that question is because I didn’t hear people on the farm talk about it much because we didn’t spend time with people who weren’t from them, so I didn’t hear them describe it up. I know when Nan would take us to our grandparents and my dad’s. She would always just talk about how we were having fun and we were planting and growing our food and we were learning a lot and that you know it was very much the idealized version of it. She certainly never talked about that we were almost always hungry and cold and without shoes. It was always like the girls are learning to ride horses and things like that.

By the way, if we would leave and go to Summertown like where Roberts from, we were told not to talk to him. As kids we didn’t talk to people from who weren’t part of the farm. Often the grownups did because we had companies that made money in other places, but we would even ride our bikes from the farm to the little like general store that was across from Robert’s house and we would be told, you know that we had to go with the grown up and the grown-up was going into and speak for us. We weren’t allowed to go in and speak for them for ourselves.

Q: Was the farm nationally known at the time you were living there?

A: It was internationally known. They were on the Donahue show which is, you know, it’s like Oprah then Time magazine in the New York Times there was a of lot of interest in U.S. and we had centers all over the world. Globally, they thought that we were doing right and that we were just people and that we were being raised in the right way. You know we had people from the farm and my family who were invited to go be on Greenpeace. At one point there were famous musicians and scientists, and you know writers who would come and spend time there because we were living in the way that people should live and not being as interested in in what they call the material plane meaning physical things.

Q: Did people on the farm think of it as like a philosophical thought experiment, or was it like a political statement?

A: Both. I remember in one of our history classes we always took history from different people’s perspective, like we had Native American history and women’s history, and one of the history classes that we took was. I remember in 5th grade history class was around socialism and communism and how countries like Russia had done it wrong and failed as with communism, but that we were doing it right.

And so, it was very much like a physical experiment and the centers around the world were designed to go in and do things like run irrigation to towns that didn’t have it and teach women in Guatemala how to nurse and care for their babies? And then it was also a philosophical experiment because Steven was considered to be on a higher level; a higher ordered person than other people. He was a spiritual leader, and he was known internationally for.

Q: Could you just talk a little bit about what the Farm’s relationship to local was?

A: Like I said, we didn’t have a lot of experience with people from off the farm. We didn’t meet very often and when we did we, you know, we were fairly protected. My dad, grandpa Dan. He was our postmaster and so he had this truck that had always all post boxes in it and so I would get to go into town with him about once a week to go pick up the Mail and then I would get to go to the store and sometimes I would be able to get a V8 or a banana or something like that. There I would hear people talk about us in a different way.

I’m not relating it to racism or anything, but the way people talked about us was kind of some of the things you hear people say about black people. As a kid, I distinctly remember somebody saying that they couldn’t believe how articulate I was and that they couldn’t believe I was clean.

I didn’t know the full extent of it until I went to public school and Robert told me not to tell anyone where I was from, and I had to sneak to get off the farm to go to school. I would leave in the dark, walk a couple of miles in the dark to the bus stop and wait for the bus to come. When I got to school, I started hearing people talk about the farm. Nobody knew I was from there, but they would say things like we didn’t know who our dad was, and that we had free loves and free drugs and all these other things.

We were called that Devil worshippers which I didn’t know what that meant but I knew it was bad. I didn’t know what they meant because we didn’t talk like that on the farm and then I was in public school for a year. My friend Peter came to school from the Farm school, so he and I knew, but we didn’t tell anyone, and then everyone, all the kids from the Farm school started to go to our public school. Then everyone knew who we were and all of a sudden, I lost my status at school. I had sleepovers at my friend’s house all the time and then I couldn’t go to people houses after they found out I was from the Farm. I was a cheerleading alternate which at our school is a really big thing but then I was kicked off the team. Teachers started treating me differently because they suddenly knew where I was from. And so it was very hard.

So, and one other thing about the locals, we had a sign at the end of our road, and we couldn’t have advertisements about where we were because people would want to attack us, throughout my whole childhood because people tried to attack us.

Q: Did adults on the farm talk about the counterculture and larger political movements outside the farm?

Yeah, so people would come to the farm you couldn’t just walk in and say I’m going to live here. You had to go through this whole process called soaking. You had to live up by the gate for a couple weeks and then hope to be sponsored by somebody and live in their house and then the house would decide if you should get membership. But there were people who came who were fleeing the draft and the local people at the local government had no idea who was there, although they tried to raid us and bust us all that. Steven went to jail for avoiding the draft at one point and they were always trying to imprison him. That’s why we had that holiday 4/20 because they came and said that we were growing weed all over the place, but we weren’t we’re growing ragweed. There were all these helicopters came and landed in our field and people and guns came after us.

Stephen would leave the farm all the time and he would preach around the world and even preach on TV. He was considered a leader and teacher of the counterculture narrative like you know now if I tell people, I’m from the farm, it’s not uncommon that people know what I’m talking about.

There was a huge amount of media attention on us. And we had our own school system and local universities would come in and send their teachers to observe us because we were presented as like an idealized version of education. So, we were very well known and very much thought to be one of the leaders of deep thinking and higher-level thinking.

Q: Do you think the reason that the farm stopped operating the way it did was because of bigger global changes? Or because of smaller things within the community?

A: It was entirely financial. The thing was that a lot of the people who lived on the farm were highly educated and came from fairly well–to–do families, however we did not make enough money to support what we were doing. There was a book publishing company which my uncle ran and you know Hops and Grampa Dan operated the ice cream company, and all those companies were meant to bring money into the farm. And we had a clinic and an ambulance, and doctors and midwives but we did not have surgical facilities and we were going into debt. Michael and my mom worked together to orchestrate what is commonly referred to as the changeover. The changeover is thought to be the end of the farm as it was because. The local bank was saying if you don’t pay back some of these loans, we’re gonna take the land. Which is why the land grant is written in such a weird way that it can never be sold because they’ve made it really complicated to protect it from being seized.

So, the changeover happened, and Nana was part of it. Auntie Shell was considered a teen elder. We had elders who made our decisions and Stephen blamed Nana and Dan for the fall of the Farm economically and blamed me for the fall of the education system.

People were told you can stay here, but you’re gonna have to pay rent, which was the first time ever.

And if your kids go to our school, you have to pay tuition. But Nobody had had any income, like I don’t remember ever seeing a dollar bill when I was little like I had no idea that paper, something that was paper could buy me something.

When the changeover happened, if you worked for a company on the farm, and you wanted to own that company, you could. The whole reason why we moved from being a commune to what was then referred to as an intentional community is the changeover, and it was entirely financial.

Steven was verbally abusive tome.

Nana and Michael were working so long and so hard and they would take a couple quarters and get a thing of M&Ms and divide them up because they knew before anyone else that what they were doing to make the changeover happen. Mom knew, and Michael knew before anyone else that the decisions they were making were going to completely alter the future of the farm.

Selected Images – Courtesy of Jen Cort