A Snapshot of Dickinson in the 1960s: Zoom Interview with Ms. Judy Rogers

By Amanda Sowah

While the 1960s and 1970s reflected progressive change and great upheaval in American history, the impact of certain changes were not always felt by those going through those moments. As a 1965 Dickinson alum, Judy Rogers narrates her experience during her time at Dickinson. Through her narration, one comes to understand that the huge components that shape history are not always understood or experienced by those who lived in those time periods. The momentous events we can pinpoint throughout history may have been insignificant to those that lived in the era.

Ms. Rogers came to Dickinson in the year 1961. Already, there were changes that separated the sixties from the previous decade. One of those foreshadowing moments for Ms. Rogers that helped characterize the progressive laws that was enacted was the fact that her family “integrated” the community of East Orange, New Jersey in the early 1950s. The prevalence and easy access to home ownership was facilitated by the G.I Bill which made home mortgages and loans much easier to get. The G.I. Bill, also known as the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944, provided educational resources, low mortgages, low interest loans and unemployment funds for war veterans.

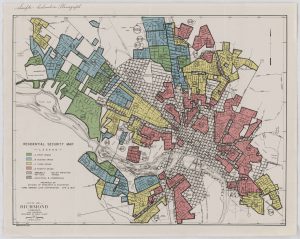

“City of Richmond, Virginia and Environs,” National Archives (1937). https://catalog.archives.gov/id/85713737

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights of 1965 call into question the existing oppressional practices that needed to change. The American Yawp chapter reminds us that while this widespread financial boost from the G.I. Bill helped many American families, black Americans were sometimes excluded from this growth. Practices like red lining, created in the 1930s through the Home Owners Loan Cooperation (HOLC), were adopted into 1960 agencies like the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) and the Veteran Administration (VA). Red lining was the process in which neighborhood were color-coded on maps to show the demography, and in-turn the financial value. The lowest valued areas were colored red and were inhabited by communities of color, specifically black people. Ms. Roger’s experiences show that not all black veterans became a victim to these discriminatory practices. Her father was a recipient of the G.I. bill, and this allowed him to buy a house for his family in East Orange. While the Rogers were lucky, they were far from the quintessential 1950s family. Ms. Rogers remembers that her parents still had to work to be able to keep the family afloat. She explains: “What was different, I think for many black families, as opposed to the idealized- on TV show, was that they really needed two incomes in order to, you know, to make it.”[1]

Yet the Rogers family was better off than most. Ms. Rogers recalls that while her nuclear family was comfortable, her other relatives were struggling in other parts of New Jersey. As a child, she would recall seeing difficult circumstances surrounding her family that lived in the city of Nork, New Jersey, when she visited them. According to her, “They didn’t own their house, they were renting, and it was city life, life was very different. Although it was still a neighborhood. I also remember you know people who weren’t doing so well.”[2] The “people” that she refers to were not specifically familial relations but rather, community members she could tell were struggling to get by. By the 1950s, black individuals in the northern cities were much more common in northern suburbs. The presence of African Americans began in the 1920s during the movement known as the Great Migration. Before the move, 90% of African Americans lived in the south and by the 1970s, 47% of them lived in the North and the West.[3] They were fleeing from lynching practices, poverty, and constant racial oppression in the south. But the north did not provide better opportunities. There held the highest unemployment rates, experienced bad working conditions, and lived in horrible conditions.

The ideals of the second World War incensed African Americans to mobilize and advocate for equality. The economic downturn in the north and racial hierarchy enforced by Jim Crow Laws ushered in the Civil Rights Movement. It began with famous protests like the Montgomery Boycott in 1953. There was also the 1954 Brown vs. Board of Education decision which ruled that segregation was illegal and required all states desegregate “with all deliberate speed.”[4] While this decision was momentous, it did not lay out a plan to ensure its enforcement, so it took several decades to have any effect. Additionally, the lynching of fourteen-year-old Emmet Till in 1955 and the failure of the Civil Rights Act in 1957 pushed the momentum of the movement.

After the Montgomery Bus Boycott, student and Christian organizations took up the mantle and began to make their demands known. Groups like the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) worked together and individually to reiterate the social injustices faced by black Americans to the media. Leaders like Martin Luther King and Malcom X rose in prominence and in popularity. The Black Panther also gained notoriety and pulled together resources to provide for their communities and used armed self-defense to fight against police brutality.

“Mid-Winter Ball,” Microcosm (1964): 76-77. http://archives.dickinson.edu/microcosm/microcosm-yearbook-1963-64

Dickinson did not reflect the Civil Rights movement. Majority of the student body were not heavily concerned with outside matters. There a few like Judy Rogers who expressed their disdain for Dickinson’s social apathy. An example of this was when the student body hosted the Midwinter Ball on the day President John F. Kennedy was assassinated. Ms. Rogers fondly remembers that “Dickinson was very different. Students were very focused on sorority and fraternity life. In fact, when President Kennedy was assassinated, we were doing the Mid-winter Ball. The students decided not to cancel it. They went to the Ball and did not care.”[6] Ms. Rogers was not alone in her remarks as several students wrote to the editor of the Dickinsonian newsletter after the event complaining about the student body’s ambivalence. A student, Steward Glenn, admonished his fellow in the following statement: “it seems to me that we might be shallow people if we react this way.”[7] Two students agreed with Glenn and emphasized that the “ball was a symptom of a definite moral disease.”[8] The Ball did not reflect all of Dickinson but its existence attests to the communal values of the student body.

While the Ball did go on, Dickinson took some steps to commemorate the death of the president. Dean of the college in 1963, Samul Magill, cancelled classes on Monday to join the rest of the nation in mourning and on Tuesday and Wednesday morning as well to give students ample time to process the events that occurred. They felt it was too late to provide accommodations to the attendees of the Ball on such short notice.[9] Additionally, there was a memorial the day of the assassination to address the tragedy before the Ball. However, to students like Glenn and Ms. Rogers the most effective decision was to cancel the Ball.

The Ball confirmed for Ms. Rogers, the student’s detachment from political issues, and in turn, the fight for social justice and equality. Ms. Rogers explains that most of these students hailed form neighboring states like “Virginia and Maryland and Pennsylvania and small suburban communities that had a conservative leaning.”[10] The conservative leaning that Ms. Rogers refers to is the implicit racism that existed in the north. As mentioned earlier, racial practices by the FHA and the VA reinforced racial stereotypes and removed racial inequality from the purview of those it did not impact. Students absorbed these differences and did not really regard the protests in the south as a universal concern. Three female students wrote to the editor with the following words: “we at Dickinson are fortunate enough to know that although the President of the United States has been assassinated, there will always be someone to take care of us.”[11] Not only does this statement speak to their privilege, but it also speaks to how disconnected they are from the ongoing social movements. So, when the president is assassinated, they can grieve about the event in a chapel and then continue their planned events.

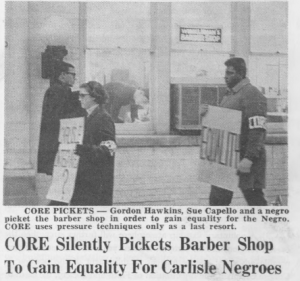

Pam White, “CORE Silently Picks Barber Shop To Gain Equality for Carlisle Negroes,” Dickinsonian, December 11, 1964, 31. https://www.flipsnack.com/cisproject/dickinsonian-1964-1965.html

There were some individuals on campus that were interested in the Civil Rights movement. They came together and formed a local chapter on the Congress of Racial Equity (CORE), another student run organization that aimed to fight racism in local spaces and on national platforms. Ms. Rogers remembers that “Ten or fifteen of us who were interested in what was going on down south. We formed a CORE chapter, and we were practicing.”[12] CORE worked in the local community, working with landlords to ensure that they were following integration laws and focusing on small businesses like the Winkleman’s barbershop. While Ms. Rogers was part of starting the organization, she was overwhelmed and uncomfortable with what she had to deal with as a protestor. She explains: “I don’t want the white folks calling me names and whatnot. And I’m not in the cell.”[14]

The 1960s brought about a lot of upheaval. While Dickinson was struggling to appease its students and pay tits due respects to social changes, Judy Rogers was looking for ways to be a part of a movement that defined her future. She tried her best to bring about change to Carlisle and the Dickinson campus. In her freshman year, she was part of a lawsuit that desegregated the local Carlisle diner. Her narration was part of the Dickinson’s experience, but it was not reflective of the values of the student body.

[1] Judith Rogers (Dickinson alum) in discussion with Amanda Sowah, April 24, 2021.

[2] Judith Rogers (Dickinson alum) in discussion with Amanda Sowah, April 24, 2021.

[3] Smithsonian: Isabel Wilkerson. “The Long-Lasting Legacy of the Great Migration,” Smithsonian Magazine, September, 2016, Accessed May 10, 2021. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/long-lasting-legacy-great-migration-180960118/.

[4] “Documents Related to Brown v. Board of Education.” National Archives and Records Administration. Accessed May 10, 2021. https://www.archives.gov/education/lessons/brown-v-board.

[5] Slonecker, Blake. “The Counterculture of the 1960s and 1970s.” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of American History. 28 Jun. 2017; Accessed 6 May. 2021. https://oxfordre.com/americanhistory/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780199329175.001.0001/acrefore-9780199329175-e-392.

[6]Steward Glenn, “Shallow Reaction,” letter to the editor, Dickinsonian, December 13, 1963, 2.

[7] Marilyn Walz and Larry S. Butler, letter to the editor, “Shallow Reaction,” Dickinsonian, December 13, 1963, 2.

[8] Samuel Magill, “Statement on College Decisions Following Assassination of President,” circa December 1963, RG 4/99 Records of the Dean of the College, Archives and Special Collections, Dickinson College, Carlisle, PA.

[9] Judith Rogers (Dickinson alum) in discussion with Amanda Sowah, April 24, 2021.

[10] Sue Godwin, Dorothy Lohman, and Renie Hirche, letter to the editor, Dickinsonian, December 13, 1963, 2.

[11] Judith Rogers (Dickinson alum) in discussion with Amanda Sowah, April 24, 2021.

[12] Judith Rogers (Dickinson alum) in discussion with Amanda Sowah, April 24, 2021.

Student Interview with Judith Rogers on April 24, 2021

Transcript:

Amanda Sowah: How would you characterize your parents’ generation?

Judy Rogers: In my parents’ generation, we were working class. My parents were working class people. What was different. I think for many black families, as opposed to the idealized-on TV show-the father working and the mom at home taking care of things-they really needed two incomes in order to, you know, to make it so my mother always work. My father was a machinist and my mother worked for Westinghouse, those that put in the filaments and light bulbs. And you stayed at your job until you retire. It’s not like today where if you didn’t like your work, you just move from job to job. That’s quite common and it’s seen as a good way of climbing. But they [her parents] stayed with their employer forever. I think my mother was at Westinghouse for 37 years.

Amanda Sowah: I know you said you were a minority in your neighborhood. What was it like for the rest of the African American community?

Judy Rogers: East Orange was a suburb and everybody every black person who lived there was in the suburbs. Now I lived in Nork as a child and that was a city and so did my grandmother and relatives. I would go back and visit and spend weekends. It was very different. They didn’t own their house, they were renting, and it was city life; life was very different. It was still a neighborhood. I also remember people who weren’t doing so well. We lived next door to the Salvation Army and black people were not allowed to live in the Salvation Army. But my mother tells me that they could use a library.

Amanda Sowah: My question is that you graduated Dickinson in the height of the Civil Rights movement. How did you experience those difficult times at Dickinson? What was the Dickinson atmosphere?

Judith Rogers: Dickinson was very different. Students were very focused on sorority and fraternity life. In fact, when President Kennedy was assassinated, we were doing the Midwinter Ball. The students decided not to cancel it. They went to the ball and did not care. I was very upset. I was like, this is our president. They were not concerned with social and worldly matters. These students mostly came from, like, Virginia and Maryland and Pennsylvania and small suburban communities that had a conservative leaning. But a few of us reacted to the sit-ins going on in the South. And you know that I had worked to desegregate the restaurants in Carlisle. But there were ten or fifteen of us who were interested in what was going on down south. We formed a CORE chapter, and we were practicing. I don’t even know why we were doing it. It seems kind of silly, but we were sort of practicing the techniques. And then I found I didn’t want the white folks calling me names and whatnot. And I’m not in the cell.

Amanda Sowah: Moving on to the seventies, the Vietnam War was interesting because there was a lot of protesting about it, and from your point of view, like, how would you describe the movement against it? There was also a lot of commotion about the Equal Rights Amendment. In contrast to your college years, how did you react to

Judy Rogers: Yeah, I protested the Vietnam War and I was anti-war. The ERA came after the blacks protested and, and got some civil rights, then other groups began to demand fights as well. So, the ERA movement were women were saying listen we have rights, and they were burning their bras. But the basis of that was the bloodshed and that went on with the Civil Rights Movement. I was also into Angela Davis when they were looking for her. And I went to lots and lots of Angela Davis protests. And when I was in grad school she was in the women’s prison, which was in the village in New York. I went to NYU, and so you know sometimes we will be protesting outside the jail to free her. Also, the Black Panthers had been formed as well. In the 70s, I had become a social worker and I went on lots of protest for Welfare Rights.

Amanda Sowah: I know you said you mentioned that Angela Davis and also other movements are happening at a time. But do you what do you think was the most impactful for you? Movements like the ERA were popping up, did you feel included?

Judy Rogers: I didn’t really feel like a part of that, because it was really about white women and the middle-class movement, they weren’t really inclusive. I felt that I had issues as a woman, but I thought I had bigger issues as a black person. So it was, you know, I really wasn’t part of that. But also, it was more of what was going on in the black community like Angela Davis and Black Panthers. And it was the moment I became a mother. In the middle of the 70s. And that, that sort of took you know a lot of my energy. The thing that I guess I did get involved in was the abortion rights part of it. Women needed to be able to control their bodies. It is our conversation today too; it’s just a lot of things we thought we conquered in the civil rights in the era keep coming up. It’s a sad lesson that nothing is permanent, and you can’t let up.