By Jessica Snydman

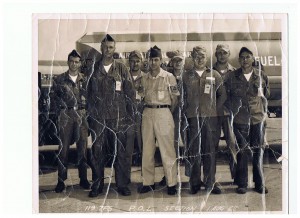

The New Jersey Air National Guard 177th Tactical Fighter Squadron. Matthew Snydman is on the far left. Courtesy of Matthew Snydman.

Matthew Snydman joined the New Jersey Air National Guard (NJANG) in his early 20’s. He was young, recently married, and working at a sweater factory in Philadelphia, PA.[1] It was the late 1950’s and at the same time, the United States found itself in a nuclear arms race with the Soviet Union.[2] In 1957, the Soviets shocked the West when they launched Sputnik, the world’s “first artificial earth satellite.”[3] The advancement proved the Soviets were developing military technology at a faster rate than expected. [4] As Matthew Snydman recalls, “the Sputnik satellite was different [from other developments in outer space and missile technology at the time] because we really didn’t want to hear anything good about the Russians and especially them beating us on anything.”[5] In response to Sputnik, the United States increased their efforts in building new military and space technology, but advancements on both sides of the conflict did not come without a price. As historian H.W. Brands explains, “the paradoxical effect of the arms race was that the more weapons the two sides deployed, the less secure they were.”[6] Snydman’s experience in the Air National Guard confirms the wisdom of that insight.

Two years after the launch of Sputnik, Snydman enlisted in the NJANG .[7] When asked why he decided to enlist he said, “There may have been a draft at that time but most of my friends were joining the NJANG as a chance to fulfill our obligation to our country and at the same time, begin our families and working careers. I think the choice of the Jersey Guard was because there were more openings available at the time than in Pennsylvania [his home state] and also the Air Force seemed a little more glamorous than the Army.”[8]

In June of 1961, Kennedy met with Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev in Vienna, where they discussed the looming issue of what to do about Berlin.[9] The city of Berlin was divided between the free, NATO-occupied Western half, and the East German and Soviet controlled, communist Eastern half.[10] Because the city of Berlin was situated “110 miles behind the Iron Curtain” in East Germany, “surrounded by Soviet troops,” the stakes were high for NATO and Western powers in West Berlin.[11] Therefore, when Khrushchev threatened “to make a peace treaty with East Germany, which would end Western access to Berlin,” Kennedy reacted firmly.[12] Soon after the meeting in Vienna, Kennedy addressed the nation in regards to how the United States would react to the Soviet Union, declaring he would increase military forces to prepare for conflict if need be, including the Air National Guard.[13]

Matthew Snydman’s unit, the 177th Tactical Fighter Squadron (177th TFS), was called into active duty that summer as a result of the speech. He remembers there being “mucho, mucho excitement!” at the prospect of being activated into the regular Air Force, saying he was “happy to finally [be] doing something more productive”.[14] Stationed at a base in Atlantic City, NJ, the 177th TFS was never actually deployed during their active duty, however. Snydman describes his work as “a refueler, the guy who, after the plane was down and positioned, plugged in my tank truck line to a port under the wing, watched the gallon counter and filled the plane with gas (JP4 fuel),” adding, “I drove a 10,000 gallon tank truck back and forth, back and forth.” He admitted it was “Boring as hell”.[15] For the most part, however, he remembers the time as being enjoyable. He sarcastically described it as a “tough life, living on or near the beach, water skiing and drinking a little beer and going to work and driving a truck and not thinking about much except if and when we were leaving for Germany which we never did”.[16]

Fortunately for Snydman, and the world, the combat deployment never came.

FOOTNOTES

[1] Email interview with Matthew Snydman, March 25, 2015.

[2] Unknown, “The Widening Conflict, 1953-1963,” in Cold War: An International History, (New York: Westview Press, 2014). [Credo Reference]

[3] H.W. Brands, American Dreams: The United States Since 1945 (New York: Penguin Books, 2010), 95.

[4] Unknown, “The Widening Conflict, 1953-1963”. [Credo Reference]

[5] Email interview with Matthew Snydman, March 25, 2015.

[6] H.W. Brands, American Dreams, 96.

[7] Email interview with Matthew Snydman, March 25, 2015.

[8] Email interview with Matthew Snydman, March 25, 2015.

[9] Unknown, “Kennedy, John Fitzgerald (1917-1963),” in A Dictionary of Contemporary History – 1945 to the Present, (Oxford: Blackwell Publishers, 1999). [Credo Reference]

[10] John F. Kennedy, “Radio and Television Report to the American People on the Berlin Crisis, July 25, 1961,” John F Kennedy Presidential Library & Museum (accessed March 2015). http://www.jfklibrary.org/Research/Research-Aids/JFK-Speeches/Berlin-Crisis_19610725.aspx

[11] Kennedy, “Radio and Television Report.”

[12] Unknown, “Kennedy, John Fitzgerald (1917-1963).” [Credo Reference]

[13] Kennedy, “Radio and Television Report.”

[14] Email interview with Matthew Snydman, March 25, 2015.

[15] Email interview with Matthew Snydman, March 25, 2015.

[16] Email interview with Matthew Snydman, March 25, 2015.