By Roberto Valentini

“Did you feel like an attack by the Russians was imminent?”

23 year-old US Army corporal Tony Bucci gazed intently out the window of the C-130 Hercules transportation plane bound for Libya. His eyes were fixed on one of the four propeller engines, which was engulfed in flames, illuminating the blackness of the night sky over the Atlantic Ocean “I was sitting in a seat on a bench next to the engine,” recalls Bucci, “I saw the fire glowing on the engine.”[1] As the plane roared forward, the blaze brought light on the many faces inside the aircraft, pensive and uncertain. It was mid-May of 1953, these men were being deployed to different theatres of the Cold War. Many of them would be sent to the intense combat zones of Korea. Bucci was not one of them, “I got lucky when they chose my number,” he tells me, “they sent me to Turkey, to a Radar station.” [2] Bucci’s recollections of the Cold War elucidate the significance of the seemingly forgotten Turkish front. This matter is only briefly hinted at by historian H.W. Brands, who describes US-Turkey Cold War relations as “a major [US] advantage over the Soviets in possessing allies not far from Soviet borders.”[3] Although the Turkish front was overshadowed in popularity by the action in Korea, Turkey was noted by US Military analysts as “the most important military factor in the Eastern Mediterranean and the Middle East.”[4]

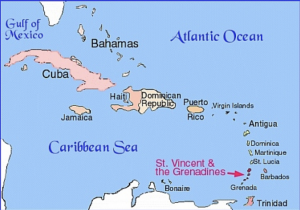

Shortly after the onset of the Cold War in 1947, the Korean War broke out, in 1950, and garnered most of the popular attention until its conclusion in the summer of 1953. In the shadow of the Korean conflict, a far less popular, yet significant Cold War front persisted, the Turkish front. American interest in Turkey was apparent long before the outbreak of Korea. In the spring of 1946, the US battleship Missouri arrived in Istanbul, Turkey, allegedly to return the body of deceased Turkish Ambassador, Mehmet Münir Ertegün, who had passed away in the US in November of the previous year. However, historians believe that “[i]n fact, the US sent the battleship to show that it would not allow the Soviet Union to expand into the Middle East and eastern Mediterranean, and that it would support Turkey as a barrier against Soviet expansion.”[5] In addition to the presence of the symbolic WWII battleship, United States foreign policy legislation substantially assisted Turkey. Former Foreign Service officer Joseph Satterthwaite recalls President Truman declaring “that the U.S. must take immediate and resolute action to support Greece and Turkey.”[6] This ‘support’, which was approved by Congress in May of 1947 would later be known as the Truman Doctrine. More economic assistance, $13 billion to a bevy of countries in Europe, in the form of the Marshall Plan would follow one month later in June[7]. The United States was dedicated to aiding and protecting Turkey in the post 1945 era predominantly, if not entirely because of its geostrategic position. Not only did Turkey serve as a barrier to the containment of Soviet expansion to the Eastern Mediterranean and Middle East, but it prevented the USSR from overtaking regions containing an abundance of oil, a crucial resource [8].

The significance of Turkey in terms of the American Cold War strategy was not widely recognized, especially not while Americans were dying in the defense of South Korea. When Tony Bucci was drafted during the Korean War in September of 1952, he anticipated that he would be traveling to Korea, “we all thought we were going to end up in Korea.”[9] Little did he know, at the time, that he would be stationed just 150 miles from the borders of the Soviet Union.

Tony Bucci arriving in Ankara, Turkey (1953). (Courtesy of Tony Bucci)

“It was a small town on the Black Sea coast called Samsun,”[10] explains the 87 year-old veteran. The radar station in which he worked with 20 other US Army Signal Corps troops lay atop one of the many peaks of the Pontic Mountains in northern Turkey, with the town of Samsun just beneath. “There was very limited housing and stuff like that… It was primitive, there were mud shacks,”[11] he says of the town. The Samsun radar station at that time, was not even an official US Military Base. “It wasn’t a barracks, we lived in apartments,” Bucci recalls [12]. It wasn’t until the Military Facilities Agreement of 1954, that the US formalized the establishment of US military bases in Turkey, and “with a Status of Forces Agreement, US military personnel, whose numbers were growing rapidly, were removed from the purview of the Turkish judicial system.” [13] Having lived in Turkey before the Status of Forces Agreement, Tony tells me that, “we weren’t allowed to approach Turkish women, it was taboo.”[14] He explained how it went against their muslim religion and also illustrated some other interesting details regarding the natives, “the natives were all living off the land… in the summertime we swam in the Black Sea. The locals didn’t swim, they didn’t even have bathing suits.” [15]

As informal as it may have seemed, the work of US military personnel in Turkey was important in not only protecting Turkey itself, but also gathering reconnaissance on Soviet movement. From his arrival on June 1st in 1953, until his departure exactly one year later in 1954, Bucci and the other men stationed there spent their days monitoring Soviet activity and tracking American U2 spy plane missions. In particular, they monitored the movement of the Soviet Naval fleet in the Black Sea. He tells me, “our radar used to pick them up and we would signal the information to the Pentagon in Washington, ‘pick up the fleet, tell us where they are’, and that was our duty every day and every night so that the generals in Washington would know what the next move was going to be.”[16] He also mentioned that the U2 spy planes could not communicate through radio in order to stay invisible to Russian radar. He explained that “the Pentagon would notify us that a plane was taking off at a certain time, and that it should be over Turkey and Russia at another time, so our station was ready to monitor that plane and make sure that the mission was completed, as far as we were concerned.”[17]

Tony Bucci by the Black Sea, 1953.(Courtesy of Tony Bucci)

United States Cold War relations with Turkey ran relatively quietly under the radar of common American public knowledge during the Korean War years. However, the Turkish front was of vital importance in the Cold War effort. In terms of protecting Turkey from Soviet forces, the United States developed “installations (over 30, with 5,000 US personnel) [that] collectively engaged in defense missions that ranged from basic logistics and supply operations to highly sophisticated communications and intelligence-collecting activities.”[18] Bucci’s radar station in Samsun is just one example of the many intelligence collecting operations. Over time, US relations with Turkey advanced, and Turkey played an even more productive role in the Cold War when their “foreign and defence ministers indicated their willingness to commit significant ground forces to help in the defence of South Korea.”[19] The US alliance with Turkey continued to contribute to the United States’ Cold War strategy even after the conclusion of the Korean War. During the arms race with the USSR, there came a point where the means of delivery of the weapons was the most significant aspect of the race. According to H.W. Brands, “Turkey offered airfields from which American bombers might not be launched against Soviet targets.”[20] This was logistical and psychological advantage. The Soviets did not occupy an airspace anywhere near as close as 150 miles from the US. Bases like Incirlik Air Force Base in Russia’s backyard were much more threatening than anything the USSR had to offer.

Posing with a C-130, Ankara, Turkey (1954). (Courtesy of Tony Bucci)

The symbiotic relationship between Turkey and the United States during the Cold War was greatly beneficial to both sides. The United States protected Turkey and gave them economic relief, while Turkey served as a barrier against communism and the oil fields of the middle east, an extra combat force in the Korean War, a neighboring air-space, and according to Joseph Satterthwaite, “the U.S. probably received more per dollar advanced [from Turkey] than in any other country,” from 1947 until 1955 [21]. Turkey’s cooperation during these years can be credited to the US’s generosity in the Marshall Plan and Truman Doctrine, and also to a threat received from the Soviet Union in 1945. In March of 1945, the Soviets decided not to renew the 1925 Treaty of Friendship and Nonaggression, that was written in 1925. This decision “met with outrage within Turkey.”[22] The combination of Soviet aggression and US generosity led to a strong US-Turkey relationship during the Cold War.

Tony Bucci’s service in Samsun was one small piece of an important, yet forgotten alliance of the Cold War. For a Korean War veteran who never fought in Korea, his role was fundamentally significant to the US efforts of the Korean War, and the Cold War overall. Although he described his time in Turkey as “dull and sometimes boring,” he acknowledges that it is “necessary for the military to know what’s going on in the world so that in the event of an attack, we know what to do.”[23] While acknowledging that Brands most likely did not have the time to include many details regarding the US-Turkey Cold War alliance, Brands’ short assertion of the importance of America’s alliance with Turkey is underwhelming. During the early Cold War period, Turkey was one of the United States’ most important allies.

Timeline

Link to Full US-Turkey Timeline

Footnotes

[1] Interview with Tony Bucci, Carlisle, Pa, December 3, 2017.

[2] Interview with Tony Bucci, Carlisle, Pa, November 7, 2017.

[3]H.W. Brands, American Dreams: The United States Since 1945 (New York: Penguin Books, 2010), 66.

[4] Richard. C. Campany, Turkey and the United States (New York: Praeger, 1986), p.80.

[5] Ao Atmaca, “The Geopolitical Origins of Turkish-American Relations: Revisiting the Cold War Years”, All Azimuth: A Journal of Foreign Policy & Peace 3, No.1 (Jan 2014): 21.

[6] Joseph C. Satterthwaite, “The Truman Doctrine: Turkey.” American Academy of Political and Social Science 401, (May 1972): 74.

[7]H.W. Brands, American Dreams: The United States Since 1945 (New York: Penguin Books, 2010), 39.

[8] AYLI ̇N GÜNEY, “An Anatomy of the Transformation of the US–Turkish Alliance: From “Cold War” to “War on Iraq.” Turkish Studies 6, no.3 (September 2005): 341-342.

[9] Interview with Tony Bucci, Carlisle, Pa, November 7, 2017.

[10] Interview with Tony Bucci, Carlisle, Pa, November 7, 2017.

[11] Interview with Tony Bucci, Carlisle, Pa, November 7, 2017.

[12] Interview with Tony Bucci, Carlisle, Pa, December 3, 2017.

[13] AYLI ̇N GÜNEY, “An Anatomy of the Transformation of the US–Turkish Alliance: From “Cold War” to “War on Iraq.” Turkish Studies 6, no.3 (September 2005): 342.

[14] Interview with Tony Bucci, Carlisle, Pa, December 3, 2017.

[15] Interview with Tony Bucci, Carlisle, Pa, November 7, 2017.

[16] Interview with Tony Bucci, Carlisle, Pa, November 7, 2017.

[17] Interview with Tony Bucci, Carlisle, Pa, December 3, 2017.

[18] Foreign Affairs and National Defense Division, U.S. Military Installations in NATO’s Southern Region (Washington DC: US Government Printing Office, 1986), p.1.

[19] Telegram from US Ambassador to Turkey to Secretary of State, dated 24 June 1950 (11 am) in FRUS, (1950),Vol.5 , p. 1281.

[20] H.W. Brands, American Dreams: The United States Since 1945 (New York: Penguin Books, 2010), 67.

[21] Joseph C. Satterthwaite, “The Truman Doctrine: Turkey.” American Academy of Political and Social Science 401, (May 1972): 74.

[22] John M. Vander Lippe, “ Forgotten Brigade of the Forgotten War: Turkey’s Participation in the Korean War.” Middle Eastern Studies 36, no.1 (January 2000): 95.

[23] Interview with Tony Bucci, Carlisle, Pa, December 3, 2017.

Selections from Interview Transcripts

-Telephone Audio Recording, Carlisle, Pa, November 7, 2017

-Telephone Audio Recording, Carlisle, Pa, December 3, 2017

Selected Transcript

From audio Nov.7:

Q. What influenced you to join the military, and when did you join?

A. “I didn’t join the military, I was drafted in September of 1952. In September I left home to go to basic training in Fort Devens, Massachusetts, and then I was transferred to [a base in] Augusta, Georgia, I was down there for six months. I didn’t know where I was going to end up, we all thought we were going to end up in Korea, but I got lucky when they chose my number, and they sent me to Turkey, to a Radar station. I was fortunate because I didn’t have to dodge the bullets, a lot of guys I trained with went to Korea.”

Q. Can you explain the specific military assignment/s of your unit?

A. “I was in the Army Signal Core, its a communications group. We were in charge of communications all over our territories. They assigned me to a radar station in Turkey, to run a power unit that supplied power to the radar station. We used to listen in on the Russians, they were only 150miles away from us. They used to listen in on us, we used to listen in on them. They used to jam the radio when we would put on “Voice of America” which transmitted all over Europe and the far East and the Middle East. The Russians would jam it, it was just a harassment, and we did the same thing to them. We used to monitor the Russian fleet, the ‘Black Sea Fleet.’ Our radar used to pick them up and we would signal the information to the Pentagon in Washington, ‘pick up the fleet, tell us where they are’, and that was our duty every day and every night so that the generals in Washington would know what the next move was going to be. And we, in Turkey, we were the first station to pick up a U2 [spy] plane and transmit the information to the pentagon and say, ‘they’ve passed our territory.’ I was happy that I got chosen to go there [Turkey], because I would’ve been sent to Korea, dodging bullets, where lots of guys were dying every day. I felt lucky, I felt very very lucky.”

Q. Can you describe where you were stationed and speak on what it was like to live there?

A. “It was a small town on the Black Sea coast called Samsun. There was very limited housing and stuff like that. The people, the natives were all living off the land. Most activity we saw was water buffalo and donkeys pulling carts. They would haul wood from the forrest, haul there stuff to the marketplace. It was primitive, there were mud shacks. My attitude there was based on the guys I served with. We played cards and things like that. There was a beer hall outside, we stood out there in the sun and drank Turkish beer. In the summertime we swam in the Black Sea. The locals didn’t swim, they didn’t even have bathing suits. It was just the Americans that knew what a beach was like, and we had an area on the Black Sea that was open to us.”

Q. What was it like coming home from your service in Turkey?

A. “It was the best feeling in the world. It was a joy. I wasn’t facing any military action [in Turkey], but we lived primitively. There were no movies, no shows, no girls, no nothing. It was very restrictive, we were limited.”

From Audio Dec. 3:

Q. What was the feeling like at your base? Did you feel like an attack by the Russians was imminent?

A. We didn’t feel that we were going to be attacked. At that time no one was really worried about it. But, its necessary for the military to know whats going on in the world so that in the event of an attack, we know what to do. We were not in fear of an attack, it was just routine maneuvers that they [the Russians] were doing. We had to send to Washington, what the ships were, the size of the ships, we could tell by radar, and where they were sailing; if the ships were going to sail just in the Black Sea or if they were going out into the Mediterranean.

Q. Can you talk about monitoring the U2 spy planes?

A. Along with the Russian fleet, we would monitor the U2 planes. They would fly across from Pakistan. We couldn’t see the plane, it would fly so high. They had cameras that would spy on Russia. One of the jobs we had was to track the U2 plane, make sure that the Pentagon knew where they were, because they couldn’t communicate [with the Pentagon], because if they did, Russia would pick up on the signal. The Pentagon would notify us that a plane was taking off at a certain time, and that it should be over Turkey and Russia at another time, so our station was ready to monitor that plane and make sure that the mission was completed, as far as we were concerned. Then it went out of our limits and it flew over a station in Rota, Spain, and they would pick up the flight. From Rota, Spain the plane would fly into Naples, Italy, and that was the end of the mission.