Desegregation, the fight against Jim Crow laws, and the greater American Civil Rights Movement of the mid-1900s routinely bring about thoughts of the battles fought and won in Southern states by martyrs such as Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Rosa Parks, and Malcolm X. Yet 1970’s Boston, the “cradle of liberty,” would play host to one of the boldest and most controversial desegregation movements of the era. Paul Long does not remember his first day at South Boston High School in the fall of 1974, nor would any of his close friends and classmates; none of them attended school that day. September 12, 1974 would mark the first day in a long fight for, and against, desegregation in the Boston Public School system. Through a busing plan put forth by Judge W. Arthur Garrity, students would be transplanted to schools outside of their home neighborhood in an effort to combat the racial imbalance the city had seen in its schools for well over a century.

The fight for desegregation in the Boston school system dates back well before Garrity’s 1974 decision. In fact, it is likely that Boston was the first city in the United States to consider and commence desegregation efforts. In the late 1700s and early 1800s, Boston schools were not segregated. Yet in the wake of harassment and mistreatment of black children by teachers and fellow students, separate schools for black students were privately funded and built as early as 1798. However, some 40 years later parents of black students began to petition the prejudice created by separate schools that they had seen form over time.[1] Sarah Roberts, a 5-year-old African American, had to travel far outside of her neighborhood, past five schools, to get to her underfunded, primarily black school. Her father, Benjamin, sued the city of Boston on behalf of a group of parents that argued the enrollment process for Boston’s school was unlawful.[2] Although the court ruled in favor of the city, the case rallied support and in 1855, the State Legislature passed the nation’s first official act of desegregation.[3] The ruling in Roberts v. The City of Boston would be the first instance of “separate but equal,” and would be later cited in the ruling of Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) that formally established the doctrine on a national level.[4] Years after this ruling, Brown v. Board of Education (1954) established that separate schools for black and white students was unconstitutional, effectively overturning Plessy v. Ferguson and Roberts v. The City of Boston.

In the wake of the Brown v. Board of Education ruling, the Massachusetts State Legislature passed the Racial Imbalance Act in 1965, requiring the integration of all schools in the state, including Boston’s. The act ruled that any school with a minority enrollment greater than fifty percent was “racially imbalanced,” and would require desegregation efforts so reconcile it. Boston was home to nearly every racially imbalanced school, and as such, the Boston School Committee strongly resisted the act. In 1972, a class action lawsuit was filed against the Boston School Committee by the NAACP on behalf of 14 black parents and 44 black students. Tallulah Morgan headed the group of plaintiffs against James Hennigan, the Chairman of the school committee. Morgan argued “the city and state had consistently denied black children equal opportunities to a public school education by intentionally creating and maintaining a segregated educational system.”[5] On Just 21, 1974, after more than two years of deliberation, the presiding Judge W. Arthur Garrity handed down his decision in favor of Morgan, ordering the immediate desegregation of Boston’s public schools through busing.

Garrity’s decision sent shockwaves throughout the Boston neighborhoods leaving residents with a variety of reactions. Paul Long, just fourteen years old at the time, looked back on the ruling: “At the time, I wasn’t too aware of the local political climate, but did know about the civil rights activism going on in the South. I didn’t think the situation was so similar in Boston. But looking

back on it all, it shouldn’t have come as such a surprise.”[6] Although court rulings in the years leading up to 1974 would clearly lead one to expect such a decision, many white Bostonians felt that Garrity’s ruling was an attack against their communities and livelihoods: “ Morgan v. Hennigan came to be perceived as Garrity v. Hennigan, even Garrity v. Boston. Across the city that fall of 1974, slogans appeared on walls, bridges, and roadways: ‘Bus Garrity,’ ‘Fuck Garrity,’ ‘Kill Garrity.’ He was hung and burned in effigy.”[7] Hundreds of people and families protested outside his home in the weeks following the ruling, and eventually federal marshals had to be stationed on his property after men had been apprehended on separate occasions en route to his house with an M-16 and a homemade bomb.[8] Furthermore, angry Bostonians sent threatening letters to his office: “Thousands of letters poured into his chambers, some reasoned arguments against busing, but most of them fierce attacks on his character and lineage (‘nigger lover,’ ‘Nazi,’ ‘child murderer’).”[9] Such hatred towards Garrity would not settle for years.

The most notable element of Garrity’s plan was the busing of students between the poor, black neighborhood of Roxbury and the white, Irish Catholic neighborhood of South Boston – polarizing communities at the time. According to Dr. William Reid, South Boston High School’s Headmaster, “It was like the hostage system of the Middle Ages, whereby the princes of opposing crowns were kept in rival kings’ courts as a preventive against war.”[10] On the first day, black and white parents alike feared for their children’s safety. In South Boston, Peggy Cosetta was worrisome, for her (white) son “Billy was starting his junior year, and like the whole South Boston High junior

class, he was now required to get on a bus and go to Roxbury. She felt like her family was caught in a nightmare. What right did the government have to force her son to leave the safety of his own neighborhood?”[11] On the other side of the city in Roxbury, Phyllis Ellison was excited for her first day of school; she had gotten up extra early and had put on a new outfit she had saved up for. However, her mother Queen felt differently. “Unlike Phyllis, Queen had risen that morning with a tinge of dread. She spent her early life in the deep South, in Mississippi, and was raised in Roxbury, where she learned quickly that black people did not often venture into South Boston… But she also knew that black children, her children, were the ones taking the risk … Phyllis was quiet and vulnerable, and Queen worried.”[12]

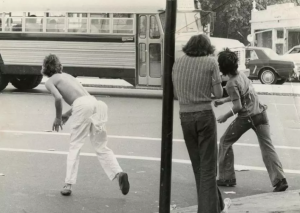

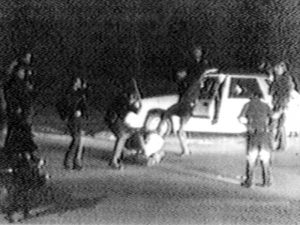

Long, like the rest of his classmates, did not go to school on the first day. “I didn’t go to school on the first day, and I’m not sure if anyone I knew did. Most families in Southie were harshly against the busing and didn’t allow their kids to go to school for some time.”[13] Throughout the city, Long and his classmates, along with their parents, siblings, and almost every other white Bostonian, lined the streets in protest of the new busing. Buses carrying black students were led by police, and upon arrival the students were escorted into the school building. All along the way, protestors threw rocks and bricks at the buses, shouted slurs and insults, and spat towards black students. “People would throw anything they could find on the ground at the buses. Others brought bricks and larger stones to throw. Some people spat on the students after they got off the buses. But everyone was yelling.”[14]

The protests and violence continued far past the first day of school. For months, white students refused to attend school, while those that did constantly harassed and attacked black students. “I don’t remember the exact date, but in mid-October I finally went to school. It was weird, but what I expected. Within the first few days I had seen black students get harassed, called names.”[15] ROAR, or Restore Our Alienated Rights, was the largest anti-busing group in Boston, led mostly by women and mothers. The group organized numerous marches and protests and were fearless in their actions: “One day in fall 1975, about 400 Charlestown mothers marched up Bunker Hill Street, clutching rosary beads and reciting the “Hail Mary.” They knelt in prayer for several minutes on the pavement between Charlestown High and the Bunker Hill Monument. And then they stood up and walked toward the police line, still in prayer, handbags held high to shield their faces. Soon a scuffle broke out between the mothers and the police. Some women were tossed to the ground.”[16] In other Boston neighborhoods, however, the conflict was not as extreme as the likes of South Boston and Charlestown. Cassandra and Wayne Twymon were bused to Brighton and saw far less conflict. “On balance, the Twymons enjoyed their year at Brighton, especially when they came home each night to watch television coverage of the violence at South Boston and Hyde Park. The kids who braved the fury of those places were street celebrities, seasoned veterans of the school wars.”[17] The worst part about those school wars, however, was that they wouldn’t end for some time. In fact, they would continue for years as the desegregation initiative continued.

In American Dreams, H.W. Brands starts and ends his discussion on the desegregation of schooling with Brown v. Board of Education. However, it is clear that the battle for desegregation ran far deeper, and over a much longer span of time. In Boston’s case, it would require multiple court rulings and over 120 years before the desegregation that was promised would be implemented. At the same time, the reasons for activism against busing were far greater than simple racism. For some, it was perceived as a threat to their way of life and community. “Normally, reasonable citizens in neighborhoods, as Salvucci put it, control ‘the crazies.’ But the reasonable types were offended by the plan and left the stage to the militants. And all sorts of persons, all across the city, viewed desegregation as “a Harvard plan for the working class man.”[18] Others questioned the success of busing in relation to its overall harm: “Although the temperature of local race relations had been rising in recent years, busing pushed it above the boiling point. What was once a generally idle racial animus between blacks and whites swelled into seething bigotry. When the buses pulled up to high schools in white neighborhoods, police had to escort black teenagers through a gauntlet of throw, n rocks and bottles; the students heard shouts of “Die, niggers, die!” and saw signs that read “Bus Them Back to Africa!” If segregation was psychologically harmful to black students, as the Supreme Court had it, how much more harmful was busing?”[19] Similarly, busing was not universally favored by black students and parents, as “whites were not the only Bostonians choking on it. Polls taken during the early days of busing show that only bare majorities of blacks favored the policy.[20] Although busing in Boston will forever leave a blemish on the city’s history, it does provide interesting insight into thoughts on desegregation in a city that was not historically segregated to the extent of the Jim Crow South. Further, Boston’s busing story uncovers concerns that Americans experienced on a micro-level during simultaneous events including the Watergate Scandal, the Cold War, and a major national financial crisis.

[1] “Prelude to Brown – 1849: Roberts v. The City of Boston.” Brown Foundation. https://brownvboard.org/content/prelude-brown-1849-roberts-v-city-boston.

[2] Miletsky, Zebulon Vance. “Before Busing: Boston’s Long Movement for Civil Rights and the Legacy of Jim Crow in the “Cradle of Liberty”.” Journal of Urban History 43, no. 2 (2017): 207.

[3] Miletsky, Zebulon Vance. “Before Busing: Boston’s Long Movement for Civil Rights and the Legacy of Jim Crow in the “Cradle of Liberty”.” Journal of Urban History 43, no. 2 (2017): 207.

[4] “Plessy v. Ferguson.” LII / Legal Information Institute. https://www.law.cornell.edu/supremecourt/text/163/537.

[5] Hornburger, Jane M. “Deep are the Roots: Busing in Boston.” The Journal of Negro Education45, no. 3 (1976): 237.

[6] Interview with Paul Long, email, November 8, 2017

[7] Lukas, J. Anthony. Common Ground. Alfred A. Knopf, 1985. 244.

[8] Lukas, J. Anthony. Common Ground. Alfred A. Knopf, 1985. 245.

[9] Lukas, J. Anthony. Common Ground. Alfred A. Knopf, 1985. 244.

[10] Formisano, Ronald P. Boston Against Busing: Race, Class, and Ethnicity in the 1960s and 1970s. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2012. 70.

[11] Irons, Meghan E., Shelley Murphy, and Jenna Russell. “History Rolled in on a Yellow School Bus.” The Boston Globe, September 7, 2014.

[12] Irons, Meghan E., Shelley Murphy, and Jenna Russell. “History Rolled in on a Yellow School Bus.” The Boston Globe, September 7, 2014.

[13] Interview with Paul Long, email, November 8, 2017

[14] Interview with Paul Long, in person, November 22, 2017

[15] Interview with Paul Long, in person, November 22, 2017

[16] Richer, Matthew. “Busing’s Boston Massacre.” Policy Review Nov/Dec 98, no. 92 (November 1998): 42-50.

[17] Lukas, J. Anthony. Common Ground. Alfred A. Knopf, 1985. 279.

[18] Formisano, Ronald P. Boston Against Busing: Race, Class, and Ethnicity in the 1960s and 1970s. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2012. 71.

[19] Richer, Matthew. “Busing’s Boston Massacre.” Policy Review Nov/Dec 98, no. 92 (November 1998): 42-50.

[20] Richer, Matthew. “Busing’s Boston Massacre.” Policy Review Nov/Dec 98, no. 92 (November 1998): 42-50.

Selected Transcript

– Email, November 8, 2017

Were you at all surprised by the decision to implement forced busing in Boston schools?

As a fourteen year old going into his freshman year, yes. At the time, I wasn’t too aware of the local political climate, but did know about the civil rights activism going on in the South. I didn’t think the situation was so similar in Boston. But looking back on it all, it shouldn’t have come as such a surprise. There was policy already in place that should have desegregated the schools, but it wasn’t until my freshman year that it was really put in place.

What was the first day of school like for you and your friends? To what extent did the violence/protesting come into the school and classroom?

Actually, I didn’t go to school on the first day, and I’m not sure if anyone I knew did. Most families in Southie were harshly against the busing and didn’t allow their kids to go to school for some time. So I cant really speak to what it was like at the beginning, but when I got there the tension was clear. There would be fights and attacks on black students in the halls day-to-day, but the real violence was outside of the school.

Who were the most active in the anti-busing campaign? Specifically, were there any groups/demographics that stood out among others? What was their reasoning behind it all?

From what I remember, the mothers of students were really the driving force behind most of the protests. But as far as the violent protests went, men and women of all ages were involved. Some were protesting the busing because they wanted to keep the community as it was, but it was clear that others protested for reasons of race. What you may not realize is that there were a significant number of black students and parents that were also against the busing. In their case, my best guess would be them seeing the cost as outweighing the benefit at the time.

What impact did the busing have on your school and community? Did things eventually go “back to normal” over time?

Certainly not during my time there. Actually, a few of my friends moved out of Boston with their families because of the busing issue. But that was because they could afford it. I never really knew what a normal day of school was like. Nearly every day there was some sort of issue regarding race and busing. It was certainly harshest at first, but over time things slowly started to come together, but never to a place where it wasn’t an clear problem.