By Amy Sparer

When Harlan Sparer was a high-schooler in Bellmore, Long Island in the early 1970’s, his mother had come up with a plan, as many mothers of soon-to-be –draft- eligible young men in the midst of the Vietnam War draft era might have done. She had begun thinking it up in the sixties, when the war began. The plan? “… for me to go to medical school in Canada when I got drafted, so that I would instantly become a Canadian citizen (…).” Sparer explained. [1] Upon noticing this, Sparer began to think about himself in relation to the conflict. “I was coming to an age where they would actually want to include me in their lovely war and I realized I really kind of didn’t want to die,” he explained “As I’m watching the Vietnam War unfold I realize there’s really no logical reason for us to be there,” Sparer remembers [2], echoing the thoughts of many Americans at the time. In his historical review, American Dreams: The United States Since 1945, H.W. Brands explains that even members of “the establishment” began to question US involvement in Vietnam, including J. William Fullbright, a Democratic senator from Arkansas, who conceded “We just don’t belong there”. [3]

Long hair and facial hair were popular for those in the countercultural movement, as shown by Harlan Sparer (left) next to his younger brothers.

The persistence of this possibly useless war led to growing sentiment against the war – notably from a growing group of people who, as Brands describes, “embraced a lifestyle as far at odds with the prevailing middle-class culture as they could make it” complete with long hair, groovy music, unkempt clothing, and a particular proclivity for illicit substances. [4] Sparer cites such substances as his introduction into the hippie lifestyle: “When I started to actually buy and sell drugs, which is the best way, I figured out, to have them on hand whenever I wanted, I began getting involved with the counterculture,” he explained. “… after I started smoking marijuana, you know, everyone that I hung out with was against the war pretty much.” [5] He and his friends, who proclaimed themselves “United Mutations”, hung out in the band room, smoked, discussed the war, and associated with “various other sort of little gangs of itinerant, strange, hippie-type people that were countercultural in nature (…).” [6] This lifestyle was often recorded at college campuses, but Sparer’s experiences were strongly associated with his high school years. This was not necessarily uncommon either – high schoolers’ association with the countercultural revolution of the 1960s and early 1970s is documented – particularly in terms of activism. [7] It took a specific turn, though, especially due to the age and place in society of the individuals involved. According to Dionne Dann’s review of Gael Graham’s Young Activists: American High School Students in the Age of Protest, “the internal structure of high schools, along with the movements within the larger society, shaped the opportunity for high school students to scrutinize their place in society (…) despite the lack of a centrally organized movement, high school student activism was a “rights revolution” (p. 9) in which the students demanded increased rights within the framework of the high school.” [8]

Harlan Sparer representing his group: “United Mutations”

“Demanding increased rights within the framework of the high school” [9] is exactly what Sparer did. He and his friends’ first protest was against the decision of the school to limit access to the band room – “they didn’t want to let us go hang out in the music room after we were done eating lunch. (…) We got a bunch of people together and we just stared down the lunch ladies – we just stood around them and surround them and just gaped and stared. (…) After a while, with 30 kids surrounding them, they got uncomfortable and walked away and we went to the band room and that was the end of that rebellion, it worked pretty well.” [10] From here, Sparer’s high school activism continued, and became more political. As Brands asserted, “The counterculture, as the phenomenon was called, wouldn’t have been so much of a counterculture if it meekly bowed to the opposition.” [11] True to this, Sparer and his friends founded an underground newspaper entitled “The Daily Mutation” with the help of their acquaintance, Irma, a young woman who belonged to Women Strike for Peace (WSP) and who had access to a Gestetner printing machine. [12] The paper, distributed mostly without school approval much to the chagrin of the Mepham High School administration, was “kind of goofy and kind of silly and kind of absurd” but was decidedly anti-war, even including advertisements for draft counseling in each issue. [13]

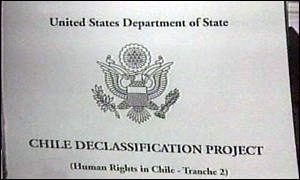

“The Daily Mutation” : Note the lower left hand section about Draft Counseling

Meanwhile, the war in east was looking dire once again. In 1970, Nixon expanded war activities into Laos and Cambodia in an attempt to carve into where the North Vietnamese troops had been taking shelter. [14] This decision was met with spectacular outrage. Brands asserts, “these efforts (…) got the attention of the antiwar movement in America. The Cambodian invasion sparked the largest protests of the war.” [15] Student protesting reached a new and terrifying high: violence broke out with student casualties occurring at both Kent State in Ohio and Jackson State in Mississippi. [16] By 1972, things were not looking up. The North Vietnamese launched the “Easter Offensive” that spring. [17] According to the Office of The Historian, Nixon’s response was to send “massive air force and naval reinforcements to bases in Indochina and Guam.” [18] The combination of these activities resonated with Sparer and his activist friends.

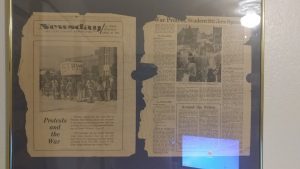

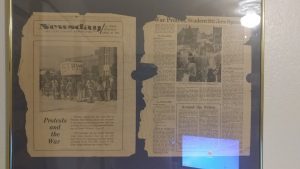

The gears began to turn. “…we decided kind of had enough of Mr. Nixon and we kind of had enough of all this BS,” Sparer explained. [19] “…with proper lubrication with the correct amount of marijuana, we decided we were going to have a protest. We were going to organize a protest for the next week and we were going to have seven converging marches. So, we got people in each of three high schools and four junior high schools and we got them all to plan this march with us (…) we ended up meeting at Wellington C. Mepham High School, which was the most centrally located school – so all these different marches converging”, Sparer elaborated. [20] On the day of the protest, Wednesday, April 19th 1972, [21] the student protesters marched to Mepham High prepared for police intervention. Sparer recounted the event: “We went in a single file, a thousand of us and we surround the grassy field on the sidewalk and then when we gave the word (…) everyone rushed the grass and there were only 20 cops to try and stop us. Needless to say, they couldn’t physically stop the rush of a thousand high school and junior high school kids. So, we all sat on the lawn and the cops took out their bullhorn and said “You must disperse immediately, you’re all going to be arrested!” and a thousand kids, in unison, just broke into spontaneously “Hell no, we won’t go! Hell no, we won’t go!” (…) The cops took us aside – they said “you’re obviously the leader of this group, come over here, we want to have a talk with you.” And so this cop paternalistically says to me and my friend Mark and my friend Jeff – “you guys! You can’t be on this school, we’re going to have to arrest all of you! Why don’t you just gather at the end of that cul-de-sac over there and we won’t bother you and you can have your demonstration over there.” [22] Sparer recalls his reply: “I said “what jail are you gonna put a thousand high school students in and how is that gonna look for you? You’re gonna have to book a bunch of underage kids, you know, you’ll have to deal with all the laws around arresting a minor. Where are you gonna put minors? You can’t put them in the jail. You don’t know what you’re talking about, you can’t incarcerate us. Now, we’re gonna go back to our demonstration. Have a great day.”[23] The protest made the front page of Long Island, New York’s local paper, Newsday, where they described the Mepham protest and local college protests in response to the renewed bombing campaign of Indochina. [24]

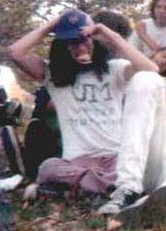

Newsday, April 20th 1972 : The Mepham High protest made the headlines

While the countercultural and activist mindset followed Harlan Sparer past his high school years, he conceded that the political aspect of the movement largely dissolved soon after the Mepham High protest when the war ended in ’73. [25] “I think generally speaking, somewhere between ’69 and ’70, there was a very big countercultural revolution that took place with anyone that was junior high school age or older where people kind of changed over and shifted over. By the mid-70s, I think, that effect was complete. The Vietnam War, when it ended, changed things a bit but it had already taken hold, and it slowly petered out in terms of the politics of it (…) by the late 70s, early 80’s it had pretty been done as far as it being a movement. There were people, you know, thinking it was groovy to do this or do that, but it wasn’t the same as when there was a political ideology attached to the marijuana smoking, to the wearing the jeans, to the wearing the t-shirt.” [26] It’s hard to say whether high school student activism had very direct influence on the Vietnam War or it’s ending. It can be hypothesized that protests in general influenced the decision making process of attempts to get out of the war. Either way, it’s clear that the work and attitudes of the counterculture population along with other anti-war activists in general impacted perceptions of the era of a whole.

Footnotes

[1] Phone Interview with Harlan Sparer, April 22, 2017

[2] Phone Interview with Harlan Sparer, April 22, 2017

[3] H.W. Brands, American Dreams: The United States Since 1945 (New York: Penguin Books, 2010), 153.

[4] H.W. Brands, American Dreams: The United States Since 1945 (New York: Penguin Books, 2010), 146.

[5] Phone Interview with Harlan Sparer, April 22, 2017

[6] Phone Interview with Harlan Sparer, April 22, 2017

[7] Dann, Dionne. Review: Young Activists: American High School Students in the Age of Protests by Gael Graham. History of Education Quarterly 47, no. 4 (2007): 510

[8] Dann, Dionne. Review: Young Activists: American High School Students in the Age of Protests by Gael Graham. History of Education Quarterly 47, no. 4 (2007): 510

[9] Dann, Dionne. Review: Young Activists: American High School Students in the Age of Protests by Gael Graham. History of Education Quarterly 47, no. 4 (2007): 510

[10] Phone Interview with Harlan Sparer, April 22, 2017

[11] H.W. Brands, American Dreams: The United States Since 1945 (New York: Penguin Books, 2010), 147.

[12] Phone Interview with Harlan Sparer, April 22, 2017

[13] Phone Interview with Harlan Sparer, April 29, 2017

[14] H.W. Brands, American Dreams: The United States Since 1945 (New York: Penguin Books, 2010), 170.

[15] H.W. Brands, American Dreams: The United States Since 1945 (New York: Penguin Books, 2010), 170.

[16] H.W. Brands, American Dreams: The United States Since 1945 (New York: Penguin Books, 2010), 170.

[17] Office of The Historian. “Ending the Vietnam War, 1969-1973.” (Last Modified????) https://history.state.gov/milestones/1969-1976/ending-vietnam

[18] Office of The Historian. “Ending the Vietnam War, 1969-1973.” (Last Modified????) https://history.state.gov/milestones/1969-1976/ending-vietnam

[19] Phone Interview with Harlan Sparer, April 22, 2017

[20] Phone Interview with Harlan Sparer, April 22, 2017

[21] “War Protests, Student Strikes Spread.” Newsday, April 20, 1972, 17.

[22] Phone Interview with Harlan Sparer, April 22, 2017

[23] Phone Interview with Harlan Sparer, April 22, 2017

[24] “War Protests, Student Strikes Spread.” Newsday, April 20, 1972, 17.

[25] Office of The Historian. “Ending the Vietnam War, 1969-1973.” (Last Modified????) https://history.state.gov/milestones/1969-1976/ending-vietnam

[26] Phone Interview with Harlan Sparer, April 22, 2017

Selected Transcript:

INTERVIEW 1: 4/22/2017

Now, I know that you were involved in sort of the countercultural movement in your high school years – can you just tell me more about what you were involved with?

“… my involvement with the counterculture began when I started smoking pot…when I started to actually buy and sell drugs, which is the best way, I figured out, to have them on hand whenever I wanted, I began getting involved with the counterculture. At that point, I started hanging out with my friends, who we later called ourselves “United Mutations” unlike all the other kids in high school back then who were all really interested in the grateful dead, or were interested in cars- those were the greasers, the hippies were involved with the grateful dead – and then the jocks were involved with athletics, of course, and the geeks were the ones that persisted – all they did was do math basically and hang out. And of course, I used to do some interesting stuff. We would get together periodically and get together in the band room- that was kind of a fun thing I would do (…) we would invent songs, and write and have lots of fun- playing music and inventing music and jamming (…) In the lunch room, I met my friends Mark and Scott and later Jeff and we ended up finding out that we each liked Frank Zappa (…) we started a garage band. This is because, in the 1970s, everyone had a garage band. And one of the things you did in the 70s was you’d get together with your friends and the notable time we’d get together with our friends was, of course, when our parents weren’t home, and then we’d have everyone leave just as the parents, just before the parents would arrive, hopefully, although in some cases that didn’t happen. So, we used to hang out with a group of people, we used to hang out, alternatively, at Jones Beach in the summer and at this park called Eisenhower Park, which used to be called Salisbury Park. This is in Nassau County, of course. And we would get together with these people, and, you know, we’d gradually got involved with both our rock band and our friends which were called the “Jones Beach Bums” which were a combination of groups like “the wheat chips” and “united mutations” and various other sort of little gangs of itinerant, strange, hippie-type people that were countercultural in nature (…).

Later on in school, we had the infamous lunch protest – that was the first protest we did. What they decided was that they didn’t want to let us go hang out in the music room after we were done eating lunch. (…) We got a bunch of people together and we just stared down the lunch ladies – we just stood around them and surround them and just gaped and stared. (…) After a while, with 30 kids surrounding them, they got uncomfortable and walked away and we went to the band room and that was the end of that rebellion, it worked pretty well. Drunk with our power, of course, later on, something else happened – Kent State happened, and, you know, four college students got shot by national guardsman in Ohio and Nixon announced that he was going to Bomb Cambodia. This is during the Vietnam War, and we decided kind of had enough of Mr. Nixon and we kind of had enough of all this BS, so we got together at this guy John’s house (…) of course with proper lubrication with the correct amount of marijuana, we decided we were going to have a protest. We were going to organize a protest for the next week and we were going to have seven converging marches. So, we got people in each of three high schools and four junior high schools and we got them all to plan this march with us. And of course one high school we’d march to, so they just were involved with shutting down the school (…) we ended up meeting at (…) Wellington C Mepham High School, which was the most centrally located school – so all these different marches converging. Now, we knew, as we were getting high, that the cops didn’t want us to close down the school and they were gonna try and stop us. So, we devised a plan: what we were gonna do was surround them, ‘cause we figured there was going to be around a thousand of us at least and they would only be around 10 or 20 cops. Well, we weren’t surprised: turns out there were about 20 or 30 cops and of course they bravely stood by the lawn in front of the school -We were all gathered kind of in a loosely aggregated group in the street – saying “you can’t get on the lawn, you have to go back”. We, of course, had our plan, so we did with this particular school (…) an old 1940’s built school – it had this big sidewalk surrounding the school and then it had these grassy fields surrounded by sidewalk (…). We went in a single file, a thousand of us and we surround the grassy field on the sidewalk and then when we gave the word (…) everyone rushed the grass and there were only 20 cops to try and stop us. Needless to say, they couldn’t physically stop the rush of a thousand high school and junior high school kids. So, we all sat on the lawn and the cops took out their bullhorn and said “You must disperse immediately, you’re all going to be arrested!” and a thousand kids, in unison, just broke into spontaneously “hell no, we won’t go, hell no, we won’t go.” And we kept saying that, of course. Needless to say, our disruption in the high school worked and everyone started hanging out the windows wondering what the heck was going on, because they knew what was going on, because they had been told – they’re like “Oh cool! It’s a demonstration!” and the cops took us aside – they said “you’re obviously the leader of this group, come over here, we want to have a talk with you.” And so this cop paternalistically says to me and my friend Mark and my friend Jeff – “you guys! You can’t be on this school, we’re going to have to arrest all of you! Why don’t you just gather at the end of that cul-de-sac over there and we won’t bother you and you can have your demonstration over there.” It’s a dead-end street, they wanted to let us sit on the concrete. And I said to the cop, I said “listen”, I said “what jail are you gonna put a thousand high school students in and how is that gonna look for you? You’re gonna have to book a bunch of underage kids, you know, you’ll have to deal with all the laws around arresting a minor. Where are you gonna put minors? You can’t put them in the jail. You don’t know what you’re talking about, you can’t incarcerate us. Now, we’re gonna go back to our demonstration. Have a great day.” And we walked back over and sat we down. We had our demonstration and we closed down the school.

Would you say the main motivation for that was the Kent State shooting?

Yeah, it was that and the Cambodia bombing.

What were your opinions, specifically, about the Vietnam War at that point?

Well, you know, it started a while back when they first started the Vietnam war in the 60s and I noticed that my mother had a plan – she had this plan for me to go to medical school in Canada when I got drafted, so that I would instantly become a Canadian citizen (…). As I’m watching the Vietnam War unfold I realize there’s really no logical reason for us to be there – and this was before I had become politically active in any way at all. And as time went on it became more of a focal point as I realized I was coming to an age where they would actually want to include me in their lovely war and I realized I really kind of didn’t want to die. Dying wasn’t me, as Woody Allen would say. That’s just not me. And so, I realized that I didn’t like this idea of a war and as time went on and I became a little more politically astute – although in 1968 in the student election I had voted for Richard Nixon, by the time 1969 came around, I started listening to what was happening with Eugene McCarthy and with the countercultural movement and I became infinitely more sympathetic as I titled more in that direction from just the media, my surroundings, my peers and it moved me to the point where after I started smoking marijuana, you know, everyone that I hung out with was against the war pretty much. Everyone pretty much came of a political nature. We all wanted to wear t-shirts and blue jeans and, you know, not be dressed up and, you know, not be like everybody else was. We wanted to be countercultural and I think generally speaking, somewhere between ’69 and ’70, there was a very big countercultural revolution that took place with anyone that was junior high school age or older where people kind of changed over and shifted over. By the mid-70s, I think, that effect was complete. The Vietnam War, when it ended, changed things a bit but it had already taken hold, and it slowly petered out in terms of the politics of it. The marijuana smoking, of course, continued for a while afterwards. But by the late 70s, early 80’s it had pretty been done as far as it being a movement. There were people, you know, thinking it was groovy to do this or do that, but it wasn’t the same as when there was a political ideology attached to the marijuana smoking, to the wearing the jeans, to the wearing the t-shirt.

(… )the war pretty much wound down and ended. Pretty much as that went on. It wound down… basically it wound down because we lost. So, people didn’t make as big a deal out of it because they realized it was gonna end anyway. But it was upsetting to everybody because there were all these people getting killed and why? What were we gaining out of that?

(…) There was a special handshake we had. Oh yeah, if you were in the counterculture, you gripped the other person’s thumb. It was a different handshake, and you knew someone was cool when they gave someone that handshake. So there was that. Clothing was really important too. There was a dress code. It was funny because Burnt Weenie Sandwich, that first album I had? This guy is screaming at this cop and says “you’re wearing a uniform, take off your uniform!” and Zappa makes fun of the guy. He says, “everyone in this room is wearing a uniform and don’t kid yourself.” Because it was the uniform at the time was a t-shirt and a pair of jeans – and the jeans had to be kind of raggedy- like not new. Worn jeans and a t-shirt – that was the uniform. Or a pair of cutoff shorts, it had to be denim. So that was the uniform. There were bellbottoms too. But see, the thing is that everyone wore bellbottoms after the fact. But in 1970 and 71 it was a statement to wear bellbottoms.

(…)It was all nonviolent protests. No one was hurting anyone no one was advocating hurting anyone we were just expressing ourselves in a nonviolent fashion. (…) I think we should all be able to express our opinion no matter what it is. As long as we’re not advocating harming another person. Now, when you wanna advocate harming somebody, its no longer non-violent protest. But, you know, we took a page out of Gandhi’s work and later Martin Luther King’s work by what we did and I think that nonviolent protest to this day is a very effective means of protest. (…) So, yeah, there’s nothing wrong with nonviolent protest. We did a lot of that. And that was a hallmark of the countercultural movement. It was that, it was marijuana and it was music. Those were the three big things that happened together, along with our dress code – and free love. (…) no harm to anybody – just fun and enjoyment and pleasure.

INTERVIEW 2: 4/29/17

I know that you had organized an underground newspaper. Can you tell me a little more about that?

“We had this band at the time, and we had just started, it was a little garage band called ‘The Magic Lepers”. And we were really enjoying having the band. And we decided one day that it would be fun to have an underground newspaper (…) and we wanted it to be political, too – against the war. So we got a hold of this woman, Irma Zeigus (spelling?), who we had run into from our anti-war activities, from my political activities. And Irma Zeigus was the local head of this organization called Women Strike For Peace, which was an antiwar organization of adults. And they happened to have a Gestetner stencil machine (…) and that’s how you printed things back then. (…) and so we seriously began writing, and we had several of us all writing together and having a good time with it. (…). We got the copies fresh off the presses from Irma, and it had dried out properly and we went right to the parking lot where all the students at the high school were and everyone knew it was coming and they were all anxious to read it. And in the morning, right before school, we just started giving it out to everybody. (…) At one point, I had built up enough of a reputation at Mepham High School that the vice principle there, who wasn’t the tall, broad shouldered type, but he was kind of a hatchet guy – his name was Thomas McQuillan and he was their enforcer – so we went to some program and I went there with my cabbie’s cap and my long pigtails to “Rap ‘n’ Rec” it was called – it was like, you know, for teenagers to hang out, it was an anti-drug thing. So of course we would all smoke lots of pot and then go to Rap ‘n’ Rec. It wasn’t exactly working as they thought. Bu, anyway, so I go in there and McQuillan says to me, “take your hat off!” and I said “no”. He said “I want you to take your hat off! You’re in a public place, take your hat off!” and I said “ No! I don’t have to take my hat off, it’s a free country.” And I proceed to walk. So he calls over his janitor – his name was Bumpy. Bumpy got a hold of me and started beating up on me, threw me out of the Rap ‘n’ Rec and threw my hat, which fell off, after me. Needless to say, we had the power of the press. So the next day I wrote an article called “Hats off to you, McQuillan!” (…). We had a good time with the underground newspaper and people enjoyed reading it and it was kind of goofy and kind of silly and kind of absurd. And there was always something about draft counseling and anti-war in it. So, that’s kind of how we rolled back then in the underground newspaper world.

(…) “My mother got a phone call (…) he said “you realize your son organized this demonstration! And he’s a communist!” She said “I’m proud of what my son did and I support what he did! So, you know what? I don’t care! And she smashed down the phone on “The Cobe”. And “The Cobe” probably didn’t know what to do at that point, because his terror program was not going to succeed.”

Do you think that there was a cultural gap there generationally generally?

I think there was one of them with the hippie movement (…) that was a massive generational change. (…) I think you see the very beginning of that change in the 60s when, you know, people were watching TV a lot and TV started to influence them. Music started to influence them and you know music was a massive influence in the late 60s. The use of marijuana also had a very very significant effect, in my opinion because I know for me, culturally, when I started smoking pot with everybody, that’s when I started to change my attitude. And it wasn’t the marijuana itself that was doing it, frankly, because if it were, it would continue to make changes. But it was the coupling of the countercultural movement with that and the fact that it was illegal. And you know even though we were protesting against the marijuana laws in the 1970s, you don’t really see the impact of those protests in the 1970s. but when those people grew up now you start to see the impact of those people. Those people now are in a position where there are a lot more of us and we’re more in a position of influence.