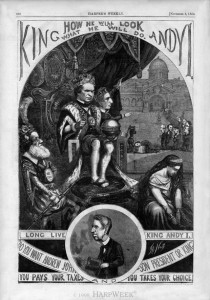

American politics has always been pretty rough, but perhaps no period was as bare-knuckled and partisan as the Reconstruction era. The confrontations involved more than just political combat between Democrats and Republicans. There were factions at odds with factions. Most notably, President Andrew Johnson waged war against Radical Republicans. These men had once been Unionist allies, but now found themselves in bitter disagreement over Reconstruction policy in the South. The result of this escalating conflict was the impeachment crisis of 1868. Thomas Nast, a leading cartoonist for Harpers Weekly depicted this crisis in a brilliant series of cartoons for the magazine. Please browse the selection of these cartoons and select one that seems to embody some of the most important insights from Eric Foner’s history of the period.

American politics has always been pretty rough, but perhaps no period was as bare-knuckled and partisan as the Reconstruction era. The confrontations involved more than just political combat between Democrats and Republicans. There were factions at odds with factions. Most notably, President Andrew Johnson waged war against Radical Republicans. These men had once been Unionist allies, but now found themselves in bitter disagreement over Reconstruction policy in the South. The result of this escalating conflict was the impeachment crisis of 1868. Thomas Nast, a leading cartoonist for Harpers Weekly depicted this crisis in a brilliant series of cartoons for the magazine. Please browse the selection of these cartoons and select one that seems to embody some of the most important insights from Eric Foner’s history of the period.

Eric Foner and Olivia Mahoney have created a web-based exhibition hosted by the University of Houston that is designed to accompany his published work on Reconstruction. Students in History 118 should browse the image gallery of the sections of the exhibit entitled “Meaning of Freedom” and “From Slave Labor to Free Labor” in order to immerse themselves in the images and stories of the formerly enslaved people fighting to establish themselves as free American citizens. These types of visual exhibitions sometimes are even more effective than print sources in conveying the experiences of ordinary people in the past. What does this exhibit reveal about the everyday life of Reconstruction for the freed people?

Prince Rivers (1822-1887)

The story of Prince Rivers embodies many of the insights which Eric Foner tries to convey in the opening chapters of his book, A Short History of Reconstruction (2015 ed.). Rivers was a “contraband,” a wartime runaway slave, who fled behind Union lines along the South Carolina coast in 1862. He joined the Union army, serving in one of the first all-black regiments, and became something of a wartime celebrity. Later, during post-war Reconstruction, he became a political figure in South Carolina. The sad ending to his career, however, suggests how, as Foner put it, Reconstruction truly became, “America’s Unfinished Revolution.” You can read about Rivers in the following two posts at the Emancipation Digital Classroom. Try to use his story to punctuate Foner’s analysis about “Wartime Reconstruction” and the various “Rehearsals for Reconstruction.”

The end of the Civil War brought about the restoration of the Union and the end of slavery, but were these two objectives really one and the same? If so, does Abraham Lincoln deserve the lion’s share of the credit for melding them together? These are the types of questions that historians argue over. So did nineteenth-century Americans. One way to engage a fresh perspective on that debate is to examine what a commercial printer in Philadelphia did with a popular image following Abraham Lincoln’s assassination in 1865. Here is what the image looked like that year:

Yet here is what the original illustration looked like in January 1863 when Thomas Nast first drew it for Harpers Weekly:

The difference is more than just color. Nast’s allegory for emancipation has now been subtly altered to give the martyred president a greater role.

The difference is more than just color. Nast’s allegory for emancipation has now been subtly altered to give the martyred president a greater role.

Below is a photograph taken at Fort Sumter on Friday, April 14, 1865. That was a special day for the Union coalition –a kind of “mission accomplished” moment as Col. Robert Anderson returned with a delegation of notables, including abolitionists like Rev. Henry Ward Beecher and William Lloyd Garrison, to raise the American flag once again over the fort in Charleston harbor where the Civil War had begun almost exactly four years earlier.

Note the cracked glass plate from this seemingly ruined photograph now in the collection of the Library of Congress. But look what happens to this image when it is digitized at a high resolution and then magnified.

Note the cracked glass plate from this seemingly ruined photograph now in the collection of the Library of Congress. But look what happens to this image when it is digitized at a high resolution and then magnified.

That’s Rev. Henry Ward Beecher speaking on the afternoon of Friday, April 14, 1865, from what he called “this pulpit of broken stone.” Originally, scholars, using magnifying glasses, thought that William Lloyd Garrison was perhaps seated on Beecher’s left.

But now we are confident at the House Divided Project that Garrison was actually seated in a special section on Beecher’s right, with other leading abolitionists and Lincoln administration notables.

But now we are confident at the House Divided Project that Garrison was actually seated in a special section on Beecher’s right, with other leading abolitionists and Lincoln administration notables.

It was obviously a moving, reflective moment for Garrison, one captured in this detail image above from right after the ceremony and by the little known story of his visit the following morning to see the grave of secessionist icon John C. Calhoun. You can read more about this episode here and here. Sometimes people are surprised by the stories that slip out of public memory and don’t make it into standard textbooks. The Garrison visit to South Carolina in April 1865 is certainly one of them, but another such lost tale involves a Dickinsonian named John A.J. Creswell, who was deeply involved in the final passage of the Thirteenth Amendment to abolish slavery, which occurred in early January 1865. Here is the image that appeared in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper to celebrate that moment.

You will notice the trio of men in the lower right hand corner, obviously prominent figures according to the illustrator. We researched them here at the college and were thrilled to discover that one of them was a Dickinsonian. It turns out that these are three congressman from the Mid-Atlantic (from left to right) Thaddeus Stevens, William D. Kelley, and John A.J. Creswell. We used a detail from that image for the cover of our first House Divided e-book, which profiles Creswell, a Dickinson graduate and Maryland politician who became one of the nation’s most important wartime abolitionists. Yet, he’s almost completely forgotten, not even mentioned in Steven Spielberg’s movie “Lincoln” (2012), which concerned passage of the amendment. You can download a free copy of Creswell’s biography, written by Dickinson college emeritus history professor John Osborne and college librarian Christine Bombaro, here. Ultimately, that might be the best way to rediscover the drama at the end of the Civil War –by seeing old stories from new perspectives.

By Matt Pasquali

Patricia Mackey was a college student at the State University of New York at Plattsburgh during the Kent State shootings, occurring on May 4, 1970. According to H.W. Brands book, American Dreams, on “hundreds of campuses across the country students boycotted classes and faculty suspended teaching in favor of discussions—which was to say, condemnation—of the war.” [1] Mackey remembers the immense cultural changes that took place on her campus after the shootings. “It was as though all hell had broken loose,” Mackey recalled about the day of the tragedy, “suddenly sleepy Plattsburgh campus became a hotbed of student unrest.” [2] Although Mackey’s experiences were common throughout American colleges and universities, her recollections during this time of turmoil are important because such memories can help show the drastic changes seen throughout American culture. However, memories from 40 years ago can become twisted over time. Ultimately, there were significant cultural changes seen post Kent State that Mackey lived through, keeping in mind that not everything was changed because of this event.

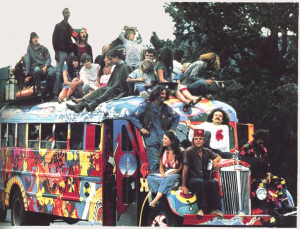

One of the most immediate changes seen during this era was among the nation’s youth. “People learned to question everything” after the shootings at Kent State. [3] “Students who had been quiet, reserved in their actions…lost the majority of their social inhibitions,” Mackey remembers. Changes in music, TV and the newly acquired drug culture became a “stronger force for expressing the public’s dissatisfaction with the status quo.” [4] The newly acquired drug culture affected everyone even if they didn’t partake in such activities. “You might not actually use marijuana or PCP…but they affected you,” recalled Mackey. Mackey noted how the drug culture caused people to “discard the traditional suit or dress of the past” and trade it in for a “psychedelic tie-dye T-shirt, bell bottom pants and sandals of the era.” She also claimed to witness her roommate “passed out in the dorm’s elevator,” an “over-drugged” student leap out of his dorm room on the sixth floor, and she claimed that the new trend of smoking marijuana caused her clothes to “smell of marijuana” regardless of if she participated in the usage or not. [5] Drug culture was everywhere and it started having effects on the entertainment business. “By way of TV at Woodstock” and “through the anti-war songs,” civilians started turning into hippies, who demonstrated their disapproval of the current wartime and aftermath of the Kent State shootings through this new type of music [6] Such rapid changes even affected athletics, where the largest impact was seen through “postponement of practices and contests.” [7]

The ongoing effects of the Kent State shootings and the Vietnam War left an impact on civil rights issues pertaining to women and blacks. “Widespread protests and the televising of the process became the norm,” Mackey noted. “Those who protested the war combined their efforts with those who protested in favor of increased rights for Blacks and women,” Mackey added. Campuses, such as Mackey’s, turned into “chaos” while students became “crazily radicalized over night.” [8] However, such chaos helped campuses across the United States become less strict about the rules regarding female students. “Young women no longer had to stay in separate dorms; they could live in co-ed dorms and use co-ed bathrooms.” [9] Mackey also notes how “no one kept track of their schedules or their whereabouts any longer” and “there was no longer a curfew for girls.” With fewer restrictions on females, there was an increased opportunity created for women after more and more people began protesting for what they believed in. As for blacks, changes were seen during the Vietnam War era, but were not as substantial as the progression seen in the movement for women’s rights. The first war blacks were allowed to enter the army was World War II, and by Vietnam times, “Blacks were drafted in higher proportional numbers than whites” but “were often required to do the most dangerous work.” [10] Blacks got what they wanted but were treated poorly. “Blacks also could not serve as officers,” Mackey adds. Even though “Blacks gained rights, at least in terms of the law” they were still treated with unequal and unfair opportunities in American society. [11]

Education was another visible cultural change seen throughout this era. One of the most immediate changes seen on Mackey’s campus after the shootings was that “no one went to class” and students attended “teach-ins” to learn about the United States’ involvement in the Vietnam War. SUNY Plattsburgh President George Angeil even allowed students to use “his office for strike-coordinating activities.” [12] Nationwide, “detrimental” effects were seen on 18% of college campuses, according to historians Richard Peterson and John Bilorusky, and “academic standards could be said to have declined or academic integrity to have been comprised” after the Kent State debacle. [13] Classes at SUNY Plattsburgh “were officially cancelled” and students were given the option to “take the grade [they] had when everything had fallen apart” or contact their professors to discuss their grades. [14] This was a nationwide effect and Peterson and Bilorusky note that in as many as one in four colleges, classes were brought to an abrupt end. [15] In the following semester, drastic changes in course content changed, as well as policies regarding dropping courses. Mackey explained how you could now “drop/change courses without a penalty” and questioning the professor “about the grade you received” was now common. [16] She also explained how by her recollection, courses “suddenly changed.” Courses started incorporating content regarding “Africa and Asia, current events, civil rights” and the “women’s liberation movement.” Courses also started incorporating “Chinese and Indian classics, world religions…and courses on what other cultures are like and…what they thought of America.” [17] Schools, such as Mackey’s, “began to study and analyze the cultures of Africa and Asia because our ignorance of such things in Vietnam.” [18]

Antiwar movements and strikes swept the nation after the Kent State shootings and the ongoing war in Vietnam. Peterson and Bilorusky state that “significant impact” was portrayed at 57 percent of American colleges after the Kent State shootings. [19] Peterson and Bilorusky also report “essentially peaceful demonstrations” on 44 percent of the American colleges. [20] Such demonstrations included “sit-ins, parades, picketing, mass meetings, rallies…and so forth.” [21] However, these peaceful protests led to threats of violence at schools such as Mackey’s. “There was a sense of urgency—a feeling that we had to get involved,” explained Mackey. “Someone came up with the idea of a march on the Air Fore Base…they were met at the gate of the base by servicemen with loaded guns who told them in no uncertain terms that if they came closer, they would be shot.” [22] The amount of student participation in antiwar movements “had exactly doubled” from January 1970 to June 1970. [23] There was such a high demand for locations to hold protest meetings that “universities bent over backwards to provide students with office space.” [24] Antiwar movements and strikes became more and more common.

During times as vulnerable as they were in the late 1960s and early 1970s, it only takes one dramatic event to spark change. The Kent State shootings created “a new wave of arson” and can be looked upon as a pivotal turning point in American culture. [25] Changes in all aspects of culture were seen: education, women’s rights, black rights, and the increased participation in antiwar movements and protests. Without the unfortunate event at Kent State University on May 4, 1970, we may not have seen such important changes in American culture.

[1] H.W. Brands, American Dreams: The United States Since 1945 (New York: Penguin Books, 2010), 170.

[2] Email interview with Patricia Mackey, March 20, 2015.

[3] [Mackey] interview.

[4] [Mackey] interview.

[5] [Mackey] interview.

[6] [Mackey] interview.

[7] Husar, John. “Big 10 Coaches Feel Effect of Campus Riots.” Chicago Tribune. 18 May 1970: c2. [Historical Newspapers].

[8] [Mackey] interview.

[9] [Mackey] interview.

[10] [Mackey] interview.

[11] [Mackey] interview.

[12] Linda Charlton, “Activity Stepped Up Here: Students Move Off Campus to Widen Protest Here,” New York Times, May 7, 1970 [ProQuest].

[13] Peterson, Richard E., and John A. Bilorusky. May 1970: The Campus Aftermath of Cambodia and Kent State. (Berkeley: Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, 1971), 25.

[14] [Mackey] interview.

[15] Peterson and Bilorusky. 16.

[16] [Mackey] interview.

[17] [Mackey] interview.

[18] [Mackey] interview.

[19] Peterson and Bilorusky. 15.

[20] Peterson and Bilorusky. 15.

[21] Peterson and Bilorusky. 15.

[22] [Mackey] interview.

[23] Beggs, Daniel C., and Henry A. Copeland. “Opinion on the Campus: Students Become More Willing to Support Beliefs with Action.” Chicago Tribune. 01 August 1970: w2. [Historical Newspaper].

[24] Oliphant, Thomas. “Universities Feel Compelled to Restrict Anti-War Activities on Campus.” Boston Globe. 19 July 1970: 1. [Historical Newspapers].

[25] Brands. 170.

By: Jordan Forry

H.W. Brands devotes three chapters of his book, American Dreams, to the early Cold War era. As the primary purpose of his book appears to be to provide an overview of modern American history in narrative form, most of these chapters focus on big picture trends. Brands does an excellent job of conveying the major events that occurred in that time period and the formal policies set out by the government. However, this big picture approach leads to many generalizations, especially regarding the home front. In this essay, I will use information gained from an interview with a woman who lived through the early Cold War (Lois Shaffer), as well as, other primary and secondary sources to both confirm Brands’ observations regarding the home front and also elaborate on parts of Brands’ story which may have been over-generalized.

Brands spends a decent amount of space describing the Berlin blockade by the Soviets and the corresponding airlift conducted by the U.S. in 1948-1949. He describes Truman as being determined to “not be pushed out of Berlin by Soviet pressure” and points out the incredible logistics required to coordinate “Hundreds of American and British cargo planes… landing and taking off as frequently as once per minute.” [1] What is lacking in this analysis of arguably the first major showdown between the U.S.S.R. and the U.S. is the attitudes of Americans on the home front. Lois Shaffer recalls that after following the situation on the radio, she and her husband became impressed with the feat that the U.S. military was able to accomplish, but she was also quick to point out that they did not necessarily follow the progress of the airlift on a day to day basis. [2] Part of the support for the airlifts on the home front undoubtedly came from national pride for what the U.S. could accomplish, but it did help that the U.S. military proclaimed its military prowess openly in the news. One example of this includes a Boston Daily Globe article from 1948 in which The Globe reported on the Air Force’s claim that it had the capacity to continue the airlift operation for as long as public support existed for the program. [3] With guarantees from the military that the U.S. could continue indefinitely with the airlifts, Americans had every reason to be optimistic with and support the airlifts under Truman’s leadership.

Brands also describes the Korean War within a policy-oriented framework that leaves out much of the story from the perspective of the home front. He describes the aggression of North Korea against South Korea as follows: “Communism was on the march and the forces of freedom needed to stop it. Korea was a test; if the United States and its allies exhibited resolve, the fighting might go no farther.” [4] Brands does get around to stating that the war, “grew unpopular,” but fails to further elaborate on the complexities of public opinion. [5] Shaffer, whose brother Lester Degroft fought in Korea, expressed conflicting opinions of the war. On one hand, she recalled that the war almost seemed like a continuation of WWII, being that the country had been at peace for only a few years between the wars. On the other hand, she claims that she and other Americans understood the significance of the war and supported Truman. [6] Others, such as Pierpooli Jr. better delineate the stages of American support and rejection of the war effort. Pierpooli claims that in the early stages of the war, Americans largely supported the war effort, but after intervention by communist China in November of 1950, widespread fear and defeatism crept in. [7] The public further lost confidence in the war effort after President Truman’s attempt to seize the striking steel mills ended in public embarrassment with a Supreme Court repudiation of his actions. [8] In sum, Pierpooli concludes that the Korean War “reflected a house divided. It engendered bitter rhetoric… (and) fostered a poisonous atmosphere of paranoia and fear…”[9] These conflicting stories of initial public support for the War and then partial to total rejection of the effort are lost in Brands’ broad overview of the War.

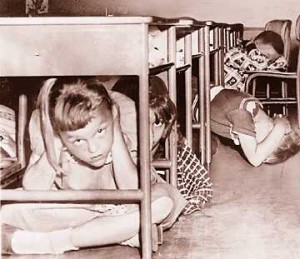

Another important aspect of life on the home front during the early Cold War was the constant threat and psychological toll of a nuclear attack. Brands suggests that Americans were comforted by the slight, but apparent, military advantage the U.S. held in the early years of the Cold War, but “the reassurance could be no more than fleeting, for the nuclear arms race continued, and the shadow across the American future-and the future of the world-grew ever longer.”[10] This quote from Brands suggests three things: that Americans were in grave danger of nuclear attack, that they accurately sensed this danger, and that they felt fear in response to these facts. However, fear may not have been as prevalent as suggested. Russell Baker recalls that just days after the first atomic bombs exploded over Nagasaki and Hiroshima, he and his mother had exchanged letters in which neither of them “indicated that we even realized anything very extraordinary had happened.” [11] Shaffer recalls that the threat of an atomic attack was always on the back of her mind, but it was not something that consumed her on a day-to-day basis or caused her to lose sleep at night. Rather, it represented a dinner conversation piece depending on the news that night. [12] This general nonchalance is reflected by the fact that polls during this period only showed a little more than half of all Americans (53%) thought there was a good or fair chance that their hometowns would be attacked. [13] This means that half of all Americans believed they faced only slim odds of experiencing a nuclear disaster, which seems to be a far less dire situation than which Brands paints. Perhaps individuals instead, as Elaine May hypothesizes, put their efforts into building a family, instead of fearing for the future, as the “home represented a source of meaning and security in a world run amok.” [14]

Students demonstrating “Duck and Cover” Circa 1950. Photo Credit: http://undergroundbombshelter.com/news/w….

On the other hand, Americans did have things to fear and did take actions and altered their lifestyles in significant ways to combat the threat of a nuclear attack. For example, Shaffer remembers schools started to have bomb drills and the government encouraged citizens to consider building bomb shelters, even as she and her neighbors did not build them for lack of money.[15] The bomb drills Shaffer recalls are most likely the “Duck and Cover” program that the U.S. government started running in schools that instructed kids to seek shelter under desks, chairs, or against walls whenever they heard an explosion or saw the flash of the bomb. [16] Also, while Shaffer never built a bomb shelter for her family, some cities, such as New York, petitioned the federal government for money to construct such facilities. In 1950, the City Planning Commissioners from New York City determined the cost of building bomb shelters for New York City would total $450,000,000, and that this project represented something “that is practical, can be completed within a reasonable time, and that is needed in view of the world situation.” [17] Finally, in addition to bomb shelters, some individuals also took steps to ensure that they and their families would be ready to survive a nuclear disaster after the initial blast. This would require having enough food stocked to last through the apocalypse. As more and more people sought to prepare themselves for the worst, guides, such as “Grandma’s Pantry to Nuclear Survival,” arose that provided recommendations for how much water, food, and other essentials to have on hand.[18]

In conclusion, life on the home front during the early Cold War was complicated. One of the drawbacks of writing a seventy year narrative of U.S. history like Brands does is it forces one to focus on the overarching themes and policies in American history and can cause one to overlook the complexities of certain times or the effects of certain historical events on the lives of ordinary Americans. By exploring other primary sources from the time, by interviewing a historical witness of the period, and by analyzing other secondary sources, a more complex picture of the U.S. home front during the early Cold War develops; one in which people are allowed to have differences in opinion and experiences. Through this analysis, it becomes evident that although the Cold War weighed heavily on everyone’s minds, it did not completely consume the day-to-day lives of all Americans. In these ways, life on the home front was more complicated than Brands is able to convey in American Dreams.

Footnotes:

1. H. W. Brands, The United States Since 1945: American Dreams (New York: Penguin Books, 2010), 40-41.

2. Interview with Lois Shaffer, Spring Grove, PA, March 12, 2015. (Interview was conducted face-to-face, but not recorded. As such, all material used in the paper is a close approximation of responses given unless quotations are provided).

3. Carlyle Holt, “Lemay Declares U.S. can Maintain Berlin Airlift as Long as Necessary,”Daily Boston Globe, September 14, 1948 (Pro-Quest).

4. Brands, American Dreams, 56.

5. Ibid., 58.

6. Interview with Lois Shaffer, March 12, 2015.

7. Paul G. Pierpaoli, Jr., “Truman’s Other War: The Battle for the American Home Front, 1950-1953,” OAH Magazine of History 14, no. 3 (2000):16-17 (JSTOR).

8. Ibid., 18.

9. Ibid., 19.

10. Brands, American Dreams, 67.

11. Russell Baker, Growing Up (New York: Penguin Books, 1982), 292.

12. Interview with Lois Shaffer, March 12, 2015.

13. Elaine Tyler May, Homeward Bound: American Families in the Cold War Era (New York: Basic Books, 2008), 25 (eBook).

14. Ibid., 26-27.

15. Interview with Lois Shaffer, March 12, 2015.

16. “Duck and Cover,” U.S. Federal Civil Defense Administration Video,9:15 (1951), posted by Archer Productions Incorporated, 2004. https://archive.org/details/DuckandC1951.

17. “Atomic Bomb Shelters?,” The New York Times, August 7, 1950 (Pro-Quest).

18. May, Homeward Bound, 100-101.

By Caly McCarthy

2020 Preface Written By Author

Recently, I was on Facebook and saw a post from the Dickinson History Department regarding the Pinsker Student Hall of Fame. I followed the link and was tickled to see my oral history from 2015 there. However, as I was re-reading it, to be honest, I was cringing at how I framed things.

When I wrote this narrative five years ago I thought that it was a fine piece of oral history, but I no longer hold this position. I failed to acknowledge even once that “riot” is a loaded term that frequently gets employed along racial lines. I should not have used the phrase “young blacks.” I should have contextualized my dad’s comment about “smoldering resentment” to emphasize the inequality that Black people face living amid racist systems. I should not have leaned on a superficial understanding of MLK’s commitment to nonviolence to decry the looting and arson that followed his assassination. I should have questioned the use of the National Guard and martial law in DC.

I thought I was being neutral. I thought that I was simply portraying my dad’s experience. Instead, I unwittingly dismissed the chronic reality of racism in our country by centering this moment in history on property damage and white fear. I offer this preface as an invitation to accountability. Because the way we frame stories about race, violence, fear, and property damage have very real implications for whether we amplify or delegitimize Black lives, cries, and calls for change.

Original 2015 Oral History

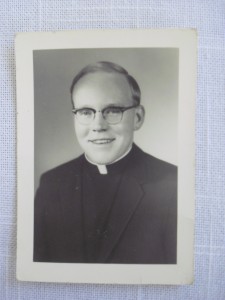

Photograph of Father Joe in 1969, one year after McCarthy was ordained a deacon.

On the day that James Earl Ray assassinated esteemed civil rights leader, Martin Luther King Jr., Joseph McCarthy was ordained a sub-deacon of the Catholic Church in Washington, D.C.[1] Historian H.W. Brands argues that word of Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination “flashed across the continent and triggered the largest wave of riots to date.”[2] Though cities throughout the nation erupted into riots, civil unrest in Washington, D.C. was especially strong. McCarthy remembers climbing on the rooftop of Catholic University, surveying the city, and observing that “[w]hole blocks were on fire.”[3] McCarthy’s recollections of the riots in Washington, D.C. illustrate the fear and confusion of the time immediately following MLK’s assassination. His recollections of this single uprising offer a vivid account of the race riots that dominated America in the late 1960s.

In preparation for his ordination, McCarthy had attended Montford Prep, a boarding school in New York state. He later attended St. Mary’s College in Kentucky for his undergraduate degree, where he majored in philosophy and minored in classical languages. After graduation he continued study at Kenrick Seminary of St. Louis, Missouri, and Catholic University of Washington, D.C.. On April 4, 1968, McCarthy was just shy of 28 years old. He had lived in Washington, D.C. for three years, and the violence that erupted did not come as a total surprise. He recalls identifying a feeling of “smoldering resentment” among young blacks whom he encountered while walking and taking the bus day after day.[4] Although no one was explicitly hostile towards him, there was a palpable sense of tension, evident by glares and body language. He posits that, unlike previous generations, young blacks had exposure to television. This medium regularly showcased a white standard of living unattainable for blacks and broadcast news of urban violence based on racial tensions. It made injustices more visible, and McCarthy suggests, fed frustration among the black community.[5]

The race riots that plagued the 1960s were manifestations of frustration over slow progress. Brands comments, “The promise of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, and the rest of Johnson’s Great Society seemed distant and often irrelevant to the trials of everyday life on the streets.”[6] Fueled by immense frustration regarding high unemployment, low-quality schools, and inadequate housing, small disputes with police escalated into urban riots. Such was the case in Watts, a neighborhood of Los Angeles, California in 1965, and in Newark, New Jersey and Detroit, Michigan in 1967. Hallmarks of the riots included looting businesses (especially, though not exclusively white-owned), setting fire to the city, and strong response by the National Guard. The riots always yielded loss of order, property, and life.[7]

The riots that followed MLK’s assassination were notable in both frequency and magnitude. Scholar Peter B. Levy asserts that “during Holy Week 1968, the United States experienced its greatest wave of social unrest since the Civil War.”[8] Nearly 130 cities in over 36 states experienced violence in the wake of MLK’s death.[9] Washington, D.C. witnessed twelve days of rioting. By the end, 13,600 troops, “more than were used in any other riot in the nation’s history, occupied the city and regained control.”[10] Before the rioting ended, 13 people died, 7,600 were arrested, and $24 million’s worth of property damage was incurred. Washington D.C. boasted 1/3 of the nation’s insurance claims for destruction that followed MLK’s death.[11]

McCarthy recalls that amid all of this unrest, his family managed to get into the city and attend his ordination. He says that they left immediately after, and that “the streets were absolutely bare. You were not allowed out on the streets. No buses. It was eerie, and sad, and frightening.”[12] In noting that no one was allowed on the streets, McCarthy references the official state of emergency that President Johnson and Mayor Walter Washington declared over the city.[13] City officials had prepared emergency measures in advance of MLK’s Poor People’s March, set for April 22, 1968. They had cause to use them earlier than planned, in light of the rioting that followed MLK’s assassination. The city trained police officers in mob psychology and urged them to have few visible officers and to avoid unnecessary use of sirens, so as to reduce targets for violence. Additionally, the training instructed officers to make arrests quietly. With regards to emergency measures, a curfew was enacted and the sale of gasoline, firearms, and alcohol was prohibited.[14] City officials enacted these policies in hopes of eliminating magnifiers of aggression. Even so, rioters disrupted the city a great deal. McCarthy remembers, “One of my friends and his wife got stopped at a red light, and a whole group of people went out and rocked their car, and this woman was like 8…8 ½ months pregnant, and it was pretty upsetting.”[15] Emergency measures may have helped minimize further physical damage to the city, but its inhabitants were rattled nonetheless.

Arson was a primary source of damage to the city, in addition to looting and rioting. Schaffer notes that when the rioting was most intense, D.C. fire stations received twenty-five to thirty calls per hour, reporting arson and requesting assistance. Upon arriving at the scene, however, fire fighters found hostile crowds who denied them access to the buildings, rendering them incapable of eliminating the fire. Although white-owned businesses were especially targeted, black-owned businesses were not immune from damage. As a strategy to minimize damage, some black-owned businesses posted signs marking themselves as “soul brothers.” While the signs may have prevented further destruction, fire damage still created two-thousand homeless and five-thousand unemployed.[16]

Martin Luther King Jr. was a national icon for non-violence. When he was assassinated, Americans around the nation mourned his death. Yet some responded to this tragic loss in a most violent manner. In doing so, rioters caused immense damage through the acts of looting and arson. They spread a spirit of fear and confusion, as is apparent from the recollections of Joe McCarthy, ordained a deacon in Washington, D.C. amid the MLK riots of April, 1968.[17]

[1] Interview with Joseph McCarthy (audio recording), Hackettstown, NJ, March 10, 2015.

[2] H.W. Brands, American Dreams: The United States since 1945 (New York: Penguin Books, 2010), 159-160.

[3] Interview with Joseph McCarthy (audio recording), Hackettstown, NJ, March 10, 2015.

[4] Interview with Joseph McCarthy (phone conversation), April 27, 2015.

[5] Interview with Joseph McCarthy (phone conversation), April 27, 2015.

[6] Brands, American Dreams, 148.

[7] Brands, American Dreams, 148-150.

[8] Peter B. Levy, “The Dream Deferred: The Assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. and the Holy Week Uprisings of 1968.” Maryland Historical Magazine 108, no. 1 (2013): 57-78.

[9] Eric Juhnke, “A City Awakened: The Kansas City Race Riot of 1968.” Gateway Heritage: The Magazine of the Missouri Historical Society 20, no. 3 (1999): 32-43 [America: History and Life].

[10] Schaffer, “The 1968 Washington Riots”: 15 [JSTOR].

[11] Schaffer, “The 1968 Washington Riots”: 5, 12 [JSTOR].

[12] Interview with Joseph McCarthy (audio recording), Hackettstown, NJ, March 10, 2015.

[13] Schaffer, “The 1968 Washington Riots”: 12 [JSTOR].

[14] Schaffer, “The 1968 Washington Riots”: 9-10, 16 [JSTOR].

[15] Interview with Joseph McCarthy (audio recording), Hackettstown, NJ, March 10, 2015.

[16] Schaffer, “The 1968 Washington Riots”: 17, 19 [JSTOR].

[17] Music clip: http://www.freesound.org/people/nicStage/sounds/1906/

By Sam Drabkin

Catherine Drabkin began working as the director of the Charlottesville AIDS support Group when she was 26. Fresh out of graduate school, Drabkin started in 1989 and would act as the director there for there years. “In the fall of 89 I started…it was my first real job out of college” Drabkin explained “the position was the first staff position that they hired, they had gotten a grant from the state of Virginia…It was really at the time when federal funding was becoming available for AIDS organizations.” [1] This memory of federal involvement in the struggle against the HIV epidemic helps document historian H.W. Brand’s insights about the evolving struggle over AIDS funding. Brand describes how President Reagan broke his silence on the issue in the mid 80’s explaining “Reagan’s administration had tried to ignore the disease….But as the gravity of the disease became undeniable, Reagan changed his position. He increased the federal budget for AIDS research, to half a billion dollars over 5 years.” [2] Drabkin however also provides more detailed information about the crisis in its later years, and thus provides a narrative of the changing of the disease for the federal government and in the public eye.

While it certainly existed in the 1970’s it was not until 1981 that AIDS was identified as disease in itself. Victoria Hardin documents this in her book AIDS at 30 explaining ” In December 1981 two physicians at Duke University reported a case of the new disease in The Lancet and proposed the name ‘gay compromise syndrome’…the first reported cases all described gay males and indelibly linked AIDS in the minds on many as a disease of homosexual men” [3] This connection between AIDS and the gay community, despite the disease’s ability to affect any demographic, would shape the federal and social response to the disease in the coming years. The equivalence of AIDS with the gay community made the conservative Reagan administration sluggish in its response to say the least. According to James Gillet, “The institutional response to AIDS in the early 1980’s was essentially nonexistent given the gravity of the epidemic, despite an awareness of AIDS among those in the CDC and the mass media”[4] However despite the silence people were getting sick people were getting sick, and dying. By the end of 1982 an estimated 618 people had died. By the end of 1983 that number had more than tripled [5] Despite the rising death tolls and media coverage at this point Drabkin didn’t pay much attention to AIDS during these first years. “I didn’t think about AIDS very much before I started working there [The AIDS Support Group]” said Drabkin “I was still in college”[6] The victims of this disease however did not sit idly as this new threat ravaged their community. Soon AIDS victims, or as they preferred people with AIDS, began marching and forming the support groups that would be precursors to ones like the one Drabkin directed. In 1984 the death toll rose by another 3000 more than doubling the deaths in 1983.[7] The enormous casualties combined with the death of famous movie star, and friend of Reagan, Rock Hudson finally became too much for the institution to ignore. Hudson’s death marked a turning point in federal policy on AIDS and funds were made available for research and treatment. The battle however was far from over, as Brands notes. “Answers came slowly. The causative agent was identified…,” he writes, “but an effective treatment, let alone a cure, was elusive. The death toll mounted to 12,000 per year in 1986 and 20,000 in 1988.”[8]

This was the climate in the U.S. when Drabkin began working as director of the AIDS Support Group. In fact, this new attention by the Reagan Administration was what allowed Drabkin to begin working at the support group. “I came in on one grant but we applied for others and suddenly we had, actually a good bit of money that we could use to do, not only services to people with AIDS but also educational outreach for prevention.” Drabkin recalled “The organization ended up growing really fast so I moved from a volunteer coordinator position to a executive director position and hired additional staff members.”[9] The mid to late 1980’s also brought another sign of hope: AZT. In 1987 an anti-HIV drug called AZT was approved by the Food and Drug Administration to use in America. [10] However the drug, while effective, was expensive and often unavailable. The price for AZT in 1989 was nearly $200 days for a seventeen day supply and to be fully effective it had to be taken at that rate for the rest of the patient’s life. The cost amounted to nearly $10,000 a year. This price made it nearly impossible for many people with AIDS. One scholar notes, “AIDS activists protested that Burroughs Wellcome was ‘profiteering’ on the misery and death the disease caused…Perhaps the most galling aspect of Burroughs Wellcome’s price tag for AZT was that taxpayers had essentially funded development of the drug but had no control over the pricing.” Eventually the tireless actions of the activist group ACT UP applied enough pressure on Burroughs Wellcome that they were forced to significantly lower the prices in 1989 to “approximately $6500.”[11] Even with these lower prices however the prices remained out of reach for many people with AIDS “I remember when it came out,” Drabkin stats. “You know I think it was still considered pretty experimental. I think there was probably a sense of relief that, you know, you had more than 18 months to live but it wasn’t really seen as a cure. It was certainly something people fought eagerly to get a hold of…It was really expensive and the organization would sometimes try to help people get the funds,” but she adds, “I remember that it was very hard to get.” [12] This moment highlights an interesting dichotomy within the anti-AIDS movement between local support groups and more action oriented activist groups. Drabkin recalls, “You know there was a big AIDS group up in Washington D.C. and they did marches where the organizers would intentionally get arrested and you know that’s not really in my personality [laughs] I don’t know think it probably did make a difference, especially for funding that came through but I felt like I could serve better by keeping my head down and just working in the local community” [13]

One of the largest obstacles facing Drabkin’s local work was the stigma that had been attached to AIDS since its discovery. Homophobia had long been mixed with fear of the disease and many spoke of the epidemic as if it were god willed. Brands reports, “By the time the disease had a new name-AIDS-it had been labeled the ‘gay disease’. Christian conservatives pointed the finger of blame at the regnant liberalism. ‘Aids is God’s judgement on a society that does not live by His rules,” Jerry Falwell intoned.” [14] These feelings was the first thing Drabkin addressed when interviewed in a 1989 newspaper article saying “All people are possible AIDS victims — when you rely on a stereotype you think you’re safe from the disease, but you aren’t.” 26 years later in 2015 Drabkin gave a more complete explanation aboiut the stigma suffered by people with AIDS. “I think in the public view, at least in our community, was that it was something that happened to ‘those’ people. So there really was a stigma. When we ran our support groups we never revealed the location where they were meeting because we didn’t want someone to, you know, come into either spy on who was coming in to the support group and broadcast the members or sort of harass them…I think certainly in the three years I was there was less of a stigma, and within another 3 to 5 years it [acceptance] became much more prevalent as the disease spread outside of the gay community.”[16]

When asked what it was like to work in AIDS relief Drabkin admitted that, while rewarding, it was exhausting work. “We were constantly working with people who were dying…there was the pressure there, that was always there….I was pretty young, I guess i didn’t appreciate what sort of toll that could take on a person, or a staff. So when I quit I had the excuse that I was pregnant and that I was going to stay at home and have the baby but I think there was a certain amount of relief because it had been a stressful job, and that wasn’t something you really acknowledged.” [17]

[1] Phone interview with Catherine Drabkin, March 25, 2015.

[2] H.W. Brands, American Dreams: The United States Since 1945 (New York: Penguin Books, 2010), 255.

[3] Victoria Hardin, AIDS in 30 (Dulles, Virginia: Potomac Books, 2012), 23.

[4] James Gillet, A Grassroots History of the AIDS/HIV Epidemic in North America (Spokane, Washington: Marquette Books LLC), 9.

[5] “Thirty Years of HIV/AIDS: Snapshots of an Epidemic.” AmfAR. Accessed May 1, 2015. http://www.amfar.org/thirty-years-of-hiv/aids-snapshots-of-an-epidemic/.

[6] Drabkin

[7] AmfAR

[8] Brands. 255.

[9] Drabkin

[10] Brands. 256.

[11] Hardin. 135-136

[12] Drabkin

[13]Ibid.

[14] Brands. 254.

[15] Clarke, Christy. “Education Provokes Community AIDS Awareness.” The Cavalier Daily [Charlottesville] 11 Apr. 1989: 6. Print.

[16] Drabkin

[17] Ibid

By Matthew Ferry

John Ferry was ten-years old when he left his mother’s West Philadelphia home in 1961. That year, he began studying at Girard College–a boarding school endowed by the will of Stephen Girard, and established as an institution for “poor, white, male orphans.” [1] The forty-three acre property surrounded by a ten-foot tall wall was established in North Philadelphia, a neighborhood that became predominately African-American during the 1940s and 1950s as whites left for the suburbs. [2] H.W. Brands described the inner city as a place where “blacks lived in substandard housing, attended substandard schools, and worked at substandard wages.” [3] For residents of North Philadelphia, Girard’s wall was a symbol of exclusion, inequality, and racism. Behind these walls Ferry spent eight years of his life until he graduated in the spring of 1969. Reflecting on his youth and the city’s struggles to integrate, Ferry vividly recalls how West Philadelphia changed from when he “was born–from all white, to all black,” and the gang violence and protests that were prevalent just beyond Girard’s wall. He also recalls when times were different. Ferry fondly remembers hot summer nights in West Philadelphia when “all the families [in the neighborhood] would sleep outside on their front porches.” [4] Ferry’s recollection reveals how Philadelphia struggled to integrate and the implications that white’s resistance to reform had for race-relations.

The rise of mass suburbs in the 1950s proved a haven for white residents who sought to escape the crowding, conditions, and cultural differences that were prevalent in the city. World War II left Philadelphia with a massive housing shortage. Over seventy-thousand houses in the city lacked a bath or were run-down, and roughly fifty percent of homes were built in the nineteenth century. [5] The Philadelphia Housing Authority attempted to improve living conditions and spearhead integration by developing high-rise public housing projects in white communities. However, residents were resistant to the introduction of poor African-Americans in their neighborhoods. The Authority could not address the demand for affordable housing or accommodate the thousands of families displaced in the city. [6] Outside of Philadelphia, thirty-six new homes were being erected daily–fitted with two bedrooms, one bathroom, a living room, and a kitchen. Known as the Levitt model, these homes sold for $7,990 and were an attractive option for former GIs or middle-class families eligible for low interest rate federal loans. [7] Irish and Ukrainian residents of North Philadelphia moved to the suburbs as blacks moved in. Similar patterns emerged in Ferry’s West Philadelphia neighborhood. As whites left the city for suburbia, blacks came to occupy the homes that were the oldest and hardest to maintain, and their high rents and mortgages provided only the worst shelter. [8]

Police activity during the Columbia Avenue riots. Courtesy of Temple University Libraries, Urban Archives.

For African American communities across the city, the North Philadelphia, Columbia Avenue riots of August 1964 instilled a new spirit of militancy and determination to challenge the pace and goals of integration. During the 1960s, around half of Philadelphia’s five-hundred and thirty-thousand African Americans lived in North Philadelphia. Residents typically only completed eight years of school and the average income was thirty percent below the city. [9] As civil rights leaders failed to address these inequalities tensions built across the city. Black’s frustration with their circumstances erupted on August 28, 1964, when a rumor circulated that police had killed a pregnant black woman on Columbia Avenue. [10] Thousands of residents took to the streets, clashed with police, broke storefronts, and looted. Rioters dramatically outnumbered the police patrolling the area, and the city deployed fifteen hundred policemen to control the crowds. Philadelphia NAACP President Cecil B. Moore and other civil rights leaders pleaded to the crowd to stop but were dismissed. To Moore’s requests, one woman responded “this is the only time in my life I’ve got a chance to get these things,” signifying that the absence of progress and circumstances blacks faced provoked the riots. [11] In the end the riots lasted three days and left two people dead, three-hundred and thirty-nine injured, and nearly three million dollars in property destroyed. [12] The Columbia Avenue riots demonstrated the frustration of African Americans with the white establishment and their desire to establish for themselves the pace and aim of integration.

Seven months after the riots, Cecil B. Moore promised to “rededicate Philadelphia’s civil rights campaigns to improving the conditions of African-Americans.” [13] Moore directed his attention to Girard College. The school’s entirely white study body and ten-foot high walls–located in the midst of North Philadelphia, were symbols of the city’s failure to address the needs of poor and working-class blacks. On May 1, 1965, the NAACP protest against Girard began with twenty demonstrators and eight-hundred police officers. The picketers demonstrated outside of Girard day and night for seven months, and the size and intensity of the crowd grew over time. Ferry recalls how teachers at Girard told him that protestors would scale the wall at night and kill him in his sleep. [14] One of the most powerful moments of the demonstrations occurred on August 3, 1965, when Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. addressed a crowd of five-thousand protestors outside of Girard’s walls. Dr. King told the crowd that Girard and its walls were “symbolic of a cancer in the body politic that must be removed before there will be freedom and democracy in this country.” [15] The Reverend reminded the demonstrators to neither fault nor wane in their efforts to reform an institution symbolic “of the rejection and deprivation inflicted on the Negro people.” [16]

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. attends rally at Girard College. Courtesy of Temple University Libraries, Urban Archives.

Moore’s campaign to integrate Girard College forced Philadelphia to realize its own dark history of discrimination and segregation at the same time the nation celebrated the end of enforced segregation in the South. While Girard’s trustees refused to concede to protestors demands, trustees President John A. Diemand met with Governor William Scranton and May James James Tate in July of 1965 to discuss legal and judicial solutions to Girard’s racial ban. In December 1965, city and state officials filed suit in United States District Court, and Moore postponed the NAACP protest campaigns against Girard College. The case moved through the court system and in March of 1968, the U.S. Court of Appeal for the Third Circuit ruled that Girard had violated the constitutional rights of seven African American applicants by refusing them admission. Girard’s board of Trustees appealed this decision to the U.S. Supreme Court, which declined to hear an appeal of the lower court ruling. [17] In the fall of 1968, four African American boys entered Girard. However, integration did not mean the school’s white students were welcoming of their new, non-white classmates. The first African American graduate of Girard, Charles Hicks, recalled how a classmate regularly threatened to kill him in his sleep. [18]

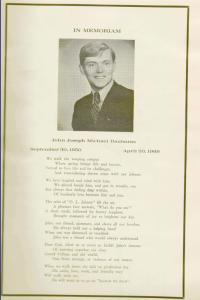

As African American communities grew agitated with the pace of progress made through nonviolent demonstrations, black youths felt compelled to take their grievances to the streets. For North Philadelphia youths in particular, their aggression was directed to the well dressed and well groomed students behind Girard’s walls–the epitome of everything the white establishment prevented blacks from being. Whenever Ferry stepped outside of Girard’s main gate he ran the risk of being attacked by local boys affiliated with a gang called the Moroccos. When a Girard College student ventured beyond the wall, there was no assurance of their safety. Even at church one Sunday, Ferry and his classmates were involved in a physical altercation against black youths. Forty-one Philadelphians were killed in gang-related conflicts in 1969. [19] That year Girard student John Daubaras was shot to death right outside of Girard’s walls in front of his two sisters and two friends. Daubaras’ death deeply shocked his classmates. Some Girard students left the school armed the day of his slaying, seeking revenge for their fallen friend. [20] Integration did not resolve relations between Girard’s white student body and North Philadelphia’s black residents. The long drawn court battles had left both North Philadelphia residents and Girard’s students resistant to cohesion beyond that required of the law. The tragic killing of Daubaras signified that North Philadelphia’s disdain towards Girard College and its white community had reach its zenith.

In the Girard College yearbook for the 1968-1969 school year, a poem written by a member of the school community is dedicated to the life of John Daubaras. In its penultimate stanza, the author wrote “Dear God, allow us to strive to fulfill John’s dreams; Of knitting together our class, Girard College and the world, Free from revenge, or violence of any means.” [21] John’s dream–his vision for the world–was exactly what civil rights leaders across the nation fought for; a world where individuals, regardless of skin color, could come together and coalesce as a single community. White communities across Philadelphia and the nation resisted efforts to integrate their neighborhoods, schools, and the workplace. The social-mobility and opportunities found in white society were lawfully denied to African Americans, who were restricted to substandard conditions. The concessions blacks gained through the courts and legislation put an end to de jure segregation and other forms of institutional discrimination. However, Institutional racism while no longer lawful, has continued to exist in every facet of society. Through reflecting on the battles won and loss during the Civil Rights Movement, it is possible to see both how far we have come and where we need to go. In better understanding the progress that has yet to be made, we may one day make Daubaras’ dream for our world a reality.

[1] “Supreme Court upholds admission of Negros to Girard College,” Observer-Reporter, 21 May 1968.

[2] Russell F. Weigley, eds, Philadelphia: A 300-Year History, (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1982), 669.

[3] H.W. Brands, American Dreams: The United States Since 1945 (New York: Penguin Books, 2010), 148.

[4] Interview with John Ferry, Philadelphia, PA, March, 14, 2015.

[5] Weigley, Philadelphia: A 300-Year History, 669.

[6] Jon C. Teaford, Review of “Public Housing, Race, and Renewal: Urban Planning in Philadelphia, 1920-1974,” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography

Vol. 113, No. 1 (Jan., 1989), 97 [JSTOR].

[7] H.W. Brands, American Dreams: The United States Since 1945, 78.

[8] Weigley, Philadelphia: A 300-Year History, 669.

[9] Sara A. Borden, “Columbia Avenue,” Civil Rights in a Northern City: Philadelphia, accessed April 28, 2015, <http://northerncity.library.temple.edu/people-and-places/columbia-avenue?civil_rights_popup=true>

[10] Matthew J. Countryman, “Why Philadelphia,” Civil Rights in a Northern City: Philadelphia, accessed April 28, 2015, <http://northerncity.library.temple.edu/content/historical-perspective/why-philadelphia>

[11] Hillary S. Kativa, “The Columbia Avenue Riots (1964),” Civil Rights in a Northern City: Philadelphia, accessed April 28, 2015, <http://northerncity.library.temple.edu/content/collections/columbia-avenue-riots/what-interpretative-essay>

[12] Weigley, Philadelphia: A 300-Year History, 676.

[13] Kativa, “The Columbia Avenue Riots (1964).”

[14] Interview with John Ferry.

[15] Carl E. Sigmond, “Community members campaign for integration of Girard College in Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1965-68,” Global Nonviolent Action Database, accessed April 29, 2015, < http://nvdatabase.swarthmore.edu/content/community-members-campaign-integration-girard-college-philadelphia-pa-usa-1965-68>

[16] John F. Morrison, “Cecil Moore vows to act united with King,” Philadelphia Evening Bulletin, August 2, 1965, George D. McDowell Philadelphia Evening Bulletin Collection, Urban Archives, Temple University Libraries, Philadelphia, PA, accessed April 30, 2015, < http://northerncity.library.temple.edu/content/cecil-moore-vows-act-united-ki>

[17] Carl E. Sigmond, “Community members campaign for integration of Girard College in Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1965-68.”

[18] Juan Williams, “The Gradual Integration of Girard College,” National Public Radio, March, 5, 2005, accessed April 29, 2015, <http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=4786582>

[19] Weigley, Philadelphia: A 300-Year History, 677.

[20] Interview with John Ferry.

[21] “In Memoriam John Joseph Michael Daubaras,” Corinthian (1969), 7.

- Police activity during the Columbia Avenue riots. Photo courtesy of Temple University Libraries, Urban Archives.

- Looting during Columbia Avenue riots. Photo courtesy of Temple University Libraries, Urban Archives.

- Civil rights demonstrators at Girard College. Photo courtesy of Temple University Libraries, Urban Archives

- Civil rights demonstrators at Girard College. Courtesy of Temple University Libraries, Urban Archives.

- Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. attends rally at Girard College. Courtesy of Temple University Libraries, Urban Archives.

Professor Todd Wronski

When Dickinson College Theatre Professor Todd Wronski was a thirteen year old boy, he witnessed an odd sight: coming silently down the steps of his family’s Mankato, Minnesota home to begin his paper route for the day, he spotted his parents huddled around a small television set. This was strange to Todd; not only were his parents not supposed to be awake this early, but they rarely watched the television that Wronski’s father had bought expressly to “watch Adlai Stevenson lose to that Eisenhower.”[1] The house ought to have been silent and dark in the comfort of the brisk summer morning, and yet here his parents were, their eyes raptly focused on the screen. It was just before six o’ clock on the morning of June 6th, 1968; Robert F. Kennedy had just been assassinated.

The murder of Bobby Kennedy set a marker for the beginning of a period of civil unrest in American history practically unmatched by any other. Coming shortly after the assassination of Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., as well as in the midst of the controversial Vietnam War, the attack seemed to solidify many Americans’ belief that society was destabilizing before their very eyes. Historian H.W. Brands illustrated this frightful atmosphere in his assertion that the political murders, widespread rioting, and demoralizing war made the liberal vision of peaceful conflict resolution “impossible to maintain.” Yet the stirring testimony of Professor Wronski regarding the social climate in his hometown following the assassination through the Cambodian bombing campaign in the spring of 1970 adds a new dimension to the turbulent period – the perspectives of average, small-town Americans and their reactions to these larger events. Wronski’s teenage years, which stretch across the most violent periods of the Vietnam War and its subsequent protests, help to represent the development of an American cynicism which followed what Brands called the effective death of the liberal vision.[2]

Wronski perhaps captured the transition from the carefree attitude of the 1967 “Summer of Love” to the chaos of 1968 in his personal comparison between the two years; whereas in ’67, protesting was “a cool thing to do” in line with the hippie movement, by the time King and Kennedy had been assassinated in June of 1968, the popular and originally peaceful movement had begun to take on a violent air. “Real extensive and hugely damaging riots,” Wronski recollected, “These people just being beat, just being clubbed.”[3] Some of the worst of these riots took place in Chicago, during the 1968 Democratic National Convention. The heart of the conflict was a deep mistrust between the United States government, which was conducting a largely unpopular war, and the rising counterculture movement, which began to straddle the line between peaceful activism and violent protest. Historian Frank Kusch argues that the brutal crackdown on the protesters stemmed from the law enforcement belief that “anyone donning counterculture dress was a threat.”[4] Little distinction was made between the hippie activists of 1967, who pleaded for peace, and the aggressive anti-war demonstrators that took to the streets in the wake of the assassinations of King and Kennedy. Brands paints the situation as a result of the “police [deciding] they’d had enough of the lefties”; in this instance, the lefties were anybody who associated themselves publicly with the activists that incited the violence.[5] Government and constituents clashed in a battle of ideals, and both sides came out the loser in a bloody struggle that left many unsure of what either had stood for in the first place.

This uncertainty caused by the breakdown of traditional social structures left many with a bad taste in their mouths. In this excerpt from the interview with Wronski, he describes the realization that he as a young teen shared with a great many American citizens witnessing these chaotic events:

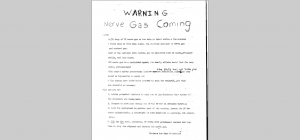

The Chicago riot was by no means a conclusive engagement; in fact, quite the opposite. As the war raged on, so did the protests, though in the wake of the excess violence many of the protesters began to question what it was they were trying to achieve. When President Nixon ordered the extension of the war into neighboring Cambodia, however, the antiwar movement once again took up arms in what Brands described as “the largest protests of the war”.[6] Many students who objected to the campaign took to criminal acts, including arson and destruction of property, while the police continued to retaliate in typical fashion. Other groups took alternate approaches, such as one student organization that tried to spread awareness of the chemical weapons they believed the US Government to be transporting through the country.[7]

However, what might have been the largest-scale protest was not necessarily the most involved on the part of the protesters. “I won’t say it was a dying gasp,” Wronski pontificated, “but it was a flare up of the protest which was beginning to wane.” Wronski recalled a high school baseball game he participated in shortly after the beginning of the bombing campaign, which was interrupted by a group of eighty to one hundred protesters. “I thought it was funny,” Wronski said of the event. “These ‘conforming non-conformists’…were just out in search of something.”[8] That the protesters found nothing more significant than a high school baseball game to break up in response to the government’s bombing of Cambodia may have tickled Wronski, but it proved to be a substantial indicator of the cynicism that had developed and festered among the American public between 1967-1970.

Even this minor altercation, however, had larger implications. “The protest movement got to be a fashion,” Wronski admitted. “But the other thing that was going on…was that the war seemed a lot closer than the wars now.”[9] The storming of the baseball game may have seemed trivial and uninspired, but the reality of the war served as a constant driving force in propelling people to action. Most everybody in small towns like Mankato knew of at least one or two people in their community who had been sent off the war, and many of those had died in the conflict. It seems understandable that in the wake of disastrous political tumult and culture clashes, all amidst the horror of a far-off yet very looming war, Americans would seek to take matters into their own hands. “You can’t be too cynical,” Wronski concluded as the ultimate takeaway from the chaotic period. Even if it means understanding why a group of people would become enraged over something as trivial as a junior varsity baseball game.

[1] Interview with Todd Wronski, Carlisle, PA, March 23, 2015.

[2] H.W. Brands, American Dreams: The United States Since 1945 (New York: Penguin Books, 2010), 162

[3] Interview with Todd Wronski, Carlisle, PA, March 23, 2015.

[4] Frank Kusch, Battleground Chicago: The Police and the 1968 Democratic National Convention (Greenwood Publishing Group, 2004) excerpted by University of Chicago Press, http://press.uchicago.edu/Misc/Chicago/465036.html

[5] Brands, American Dreams, 164

[6] Brands, American Dreams, 170

[7] “Warning! Nerve Gas Coming!,” May 1970, Steve Ludwig Photograph Collection, Harry Bridges Center for Labor Studies, University of Washington.

[8] Interview with Todd Wronski, Carlisle, PA, March 23, 2015.

[9] Interview with Todd Wronski, Carlisle, PA, March 23, 2015.