“FM SECSTATE WASHDC,” the message read, “TO AMEMBASSY NEW DELHI.” Dated September 28, 1979, the telegram from the Office of the Secretary of State to Richard Smith contained only one line of message text: “KIT MINICLIER SAYS HE IS LOOKING FORWARD TO MEETING YOU ON OCT. 3.” It was signed merely “VANCE”—Cyrus Vance, then Secretary of State.1

Secretary of State Cyrus Vance’s message about Christopher “Kit” Miniclier. Courtesy of the National Archives.

When I first saw this telegram in the Central Foreign Policy Files database in the National Archives on my initial search through the archive databases available through Dickinson, all I knew about Christopher “Kit” Miniclier was that he had graduated from Dickinson two decades before the message was sent, in 1957, and that he had written an editorial in the Dickinsonian protesting the dismissal of Professor Laurent R. LaVallee the year before that, in 1956.2 How had the Secretary of State come to know him?

An Intriguing Story

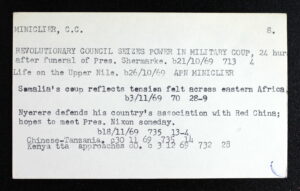

I had decided to do an preliminary search on Miniclier to see if there was any more to the LaVallee story from the perspective of students on campus, but my first stop—Ancestry.com—turned up a much more interesting story that held the key to deciphering the telegram. Among the passenger records detailing the travels of a teen-aged Christopher, his parents Louis and Lois, and other members of his family; the high school and college year books; the city directories; and the birth records were several Name/Subject index cards for the Associated Press, which list articles written by AP journalists. Under “Miniclier, C. C.” there were forty cards in all, from 1964 through 1978—a year shy of the telegram to New Delhi.

The first card has story titles like “Eric Goldman, the new idea man for Pres. Johnson” and “What’s a wife worth?” and the last lists “Institute for Religious Studies opens its doors (Peking),” but in between these are titles that reference places and political leaders in Burundi, Egypt, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Israel, Jordan, Kenya, Libya, Nigeria, Palestine, Somalia, Sudan, Tanzania, Uganda, Yugoslavia and Zambia.3 As I skimmed through the cards, I quickly realized that Miniclier’s life was a story in its own right, independent of the LaVallee case. Here was a sprawling story about journalism, international politics and interpersonal ties—from Fairfax County, VA (where Miniclier attended high school), all over North Africa, and then back to Denver, CO, and through the turbulent years of the Cold War.

One of Miniclier’s AP Name/Subject cards from October-December, 1969. Courtesy of the Associated Press.

And in the middle of all that, Dickinson College: first during his undergraduate days, and then in 1979, when he sent an article describing his impressions of China to the Dickinson magazine after he became “the first American news agency journalist to be granted a working visa, and permission to travel extensively without a delegation” in the People’s Republic of China.4

Dickinsonian Editor… and Mermaid Player

In order to find out more about Miniclier’s time at Dickinson, I browsed the digital collection at the Dickinson College Archives and Special Collections, which gave me an idea of what materials would be easy to find and what might be lurking under the surface, so to speak. In addition to Miniclier’s 1979 article on China, I found a few photographs, including one that does not seem to come from a yearbook (though it is not in his drop file). The close-up of his face (right) helped me identify him in other places, such as photographs in the Microcosm yearbooks.

The Microcosm yearbooks were a great way to find out what sort of things Miniclier had been involved in on campus. His senior portrait was accompanied by his oft-used sayings and a list of his on-campus activities, which included the Mermaid Players (started the year before he arrived to campus) and ROTC.5 Searching through the Dickinsonian for his name proved not as fruitful as I had hoped, because the editors, including him, were listed on multiple pages. However, I was able to find out that he had majored in political science and minored in economics.6

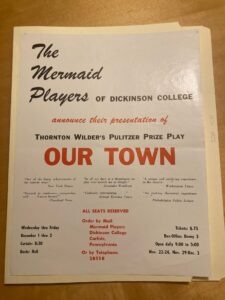

At the Dickinson Archives, archivist Malinda Triller-Doran helped me find out more about Miniclier. Although the drop file for “Miniclier, C. C.” only contained the magazine article about China, Malinda knew that he had been in a production of Our Town in 1954.

A promotional poster for “Our Town.” Tickets cost $0.75. Courtesy of the Dickinson College Archives and Special Collections.

There was a drop file for the production, which contained photographs, as well as a file for the 1954-1955 Mermaid Players season. Although only one photograph was labeled, I was able to identify Miniclier in other photographs. It turns out he was only a named character in one production that season—he was the “First Dead Man” in Our Town (and credited as “Kit Miniclier”).7 Tickets were 75 cents apiece.

My visit to the Archives didn’t turn up much that aided me in figuring out what had happened to Miniclier after he’d left Dickinson, but it gave me some background on him. I’d gotten a general sense of his character—actor, journalist, smiling in nearly every photograph. It was time to dig a little deeper.

Organizing Evidence

The AP Name/Subject Card Index had given me a good starting point for analyzing Miniclier’s journalistic activities. I headed to Newspapers.com to see what I could dig up there. Searching “Christopher Miniclier” brought up hundreds of results, most of them about our man. He’d authored so many articles! I had to scroll through the repetitive ones—“What’s a wife worth?” must have been reprinted in at least thirty papers. There were a few that were credited to him that matched the ones in the AP Name/Subject Card Index. One thing I learned by browsing through those newspapers, though, is that articles weren’t always attributed to an author. One article would have “by Christopher Miniclier (AP)” printed at the top, but the next one would simply say something like “Nairobi (AP)” without crediting an author.

Being able to see not only the individual articles but also the whole pages on which they appeared helped me to see the context in which the articles might be read. Sometimes they appeared next to sensational stories of murder. Sometimes they were the sensational stories—Miniclier himself wrote about coups, wars, child murderers, famine and assassinations—and appeared next to advertisements for baby clothes. I guess not much has changed in that respect—the biggest differences between that kind of newspaper and Twitter are the time-frame and format—but a lot has changed in the world since Kit was acting in plays at Dickinson, and Miniclier was right there in the middle of it, documenting, analyzing and exploring.

How many articles did Miniclier actually write, and where did he actually go? To get a sense of the scope, I picked out some of the more interesting articles gleaned from Newspapers.com and put them in a database using Notion. I also input the headlines of the articles in the AP Name/Subject Card Index, as well as all the evidence I’d gathered so far. By noting the date of publication (or date of event) and tagging for region and source type, I would be able to organize the list of references in a timeline, or by region. For each entry, I included all relevant photographs and notes.

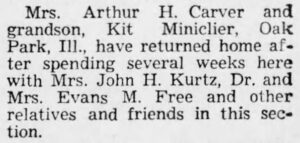

I didn’t only find articles written by Miniclier, though. Keeping in mind his nickname, I searched for both “Christopher Miniclier” and “Kit Miniclier” and found a few articles that mentioned him and his family. The earliest examples are from 1944, when he and his grandmother visited relatives in York County, PA. The “County” section of the September 6, 1944 Gazette and Daily included a segment “Brief News, Notes of Stewartstown,” which included the following paragraph:

Mrs. Arthur H. Carver and grandson, Kit Miniclier, Oak Park, ill., have returned home after spending several weeks here with Mrs. John H. Kurtz, Dr. and Mrs. Evans M. Free and other relatives and friends in this section.8

Twenty-four years later, on April 3, 1968, the same newspaper reported that Lois Carver Miniclier, Kit’s mother, was “fatally injured” in a car crash. Surviving her were her husband and three children, including Christopher, who was in Kenya for the Associated Press.9 I had collected the titles of the articles Miniclier had written during that year, but this new article put those in a new context. There was an emotional punch hidden in the puzzle of evidence that only revealed itself once I put the databases in conversation with each other.

A note on searching

With databases at our fingertips, it’s easy to get bogged down in the weeds of newspaper articles, passenger lists and duplicate records. Taking a step back can be helpful: big-picture stuff, things that wouldn’t be in an archive but are still primary sources for a biography. To get a sense of what was “out there” on the Internet, I asked Professor Google, and found a few more items of note, including an interview with Miniclier’s daughter and a 2020 death notice for his wife, Olga, whose photographs appear in the 1979 Dickinson magazine article about China.

[1] Department of State to Embassy New Delhi, Telegram 255731, September 28, 1979, 1979STATE255731, Central Foreign Policy Files, 1973-79/Electronic Telegrams, RG 59: General Records of the Department of State, National Archives (accessed April 3, 2023). [AAD]

[2] “Without Due Process Can There Be Unity?,” Dickinsonian, 23 March, 1956.

[3] Associated Press File Drawers of National, International, News Feature Name/Subject Cards, 1937–1985, Microfilm, 1114-1154, Associated Press Corporate Archives, New York, NY. [Ancestry.com]

[4] C. C. (Kit) Miniclier, “No Fortune Cookies Here,” The Dickinson College Magazine 56, no. 2 (May 1979): 2.

[5] “Christopher Carver Miniclier,” Microcosm (1957): 67.

[6] “Miniclier heads 1956 ‘Dickinsonian,'” Dickinsonian, 13 January, 1956.

[7] Mermaid Players, Our Town program, 1 December, 1954, Mermaid Players, 1954-1955, Archives and Special Collections, Dickinson College, Carlisle, PA.

[8] “Brief News, Notes of Stewartstown,” The Gazette and Daily (York, PA), September 6, 1944, Newspapers.com.

[9] “Former Resident Of Stewartstown Killed in Crash,” The Gazette and Daily (York, PA), April 3, 1968, Newspapers.com.

Bibliography

Alesbury, Elizabeth. “What’s in a Name? Giving the PA Counterpart a Global Connection.” PAEA, August 25, 2015. Accessed April 3, 2023. https://paeaonline.org/resources/public-resources/paea-news/giving-the-pa-counterpart-a-global-connection.

Associated Press File Drawers of National, International, News Feature Name/Subject Cards, 1937–1985. Microfilm, 1114-1154. Associated Press Corporate Archives, New York, NY. [Ancestry.com]

Department of State to Embassy New Delhi, Telegram 255731, September 28, 1979. 1979STATE255731, Central Foreign Policy Files, 1973-79/Electronic Telegrams, RG 59: General Records of the Department of State, National Archives (accessed April 3, 2023). [AAD]

Fairfax High School. “Fair Facts.” Fair Fac Sampler. Fairfax, VA: 1952. Internet Archive. https://archive.org/details/farefacsampler1952fair/page/92/mode/2up. Accessed on April 3, 2023.

Mermaid Players. Our Town program, 1 December, 1954. 1954-1955, Mermaid Players, Archives and Special Collections, Dickinson College, Carlisle, PA.

Microcosm (1957).

Miniclier, C. C. “No Fortune Cookies Here.” The Dickinson College Magazine 56, no. 2 (May 1979): 2-4.

“Olga Johanna Miniclier.” Starks Funeral Parlor. Accessed April 3, 2023. http://www.starksfuneral.com/obituary/2389-v0nipvhxys.

Photograph of Christopher Carver Miniclier, 1957. Photograph Archives, Students, Archives and Special Collections, Dickinson College, Carlisle, PA.

“Brief News, Notes of Stewartstown.” The Gazette and Daily (York, PA), September 6, 1944. Newspapers.com.

“Miniclier heads 1956 ‘Dickinsonian.'” Dickinsonian, 13 January, 1956.

“Without Due Process Can There Be Unity?” Dickinsonian, 23 March, 1956.

“Former Resident Of Stewartstown Killed in Crash.” The Gazette and Daily (York, PA), April 3, 1968. Newspapers.com.

Leave a Reply