After a few weeks of archival research, I considered myself to be a proper history detective, though admittedly only in training. My experience remained limited, however, and it became clear that before I could fully understand the scope of historical research I would have to decipher the mystery of microfilm. As is often best practice when learning a new skill, I started by doing something I know well: asking my friendly neighborhood archivist for help. He provided me with a finding guide for both physical newspapers kept in the archives and the reels of microfilm, and with guidebook in hand I got to work.

Step One: Basic Training

The first thing one sees when entering the microfilm section of the Dickinson College Library is the expanse of cabinets in which reels are kept. Luckily for me, these reels are organized in the finding guide alphabetically by newspaper title and chronologically by publication date. I wrote down three newspapers which had the year 1840 within their range and got to work.

The downside of venturing into the microfilm section is that my beloved archivists, Jim Gerencser and Malinda Triller-Doran, don’t have jurisdiction there. As such, I had to make new connections, and thus began with the receptionist at the basement circulation desk. She sent me upstairs to the main desk, where a supervisor and student worker were excited to try their hand at the machine. With their guidance, I was able to learn some of the basics, and once we had the first reel in the rest was more or less intuitive.

The reels of film resemble VHS tapes removed from their box, and the process of playing and rewinding them was very tactile and satisfying. Being able to physically see the little pictures moving on the tape was far more engaging than scrolling through digitized archives online, even if it did take a little more skill and finesse.

Step Two: Finding the Reels

The three newspapers I identified in the finding guide were The Carlisle Herald and Expositor, The American Volunteer, and The Republican. Unfortunately, the run of The Republican, though listed as ranging from 1835-1891, actually had a gap during the time I was interested in studying, but with the information in the guide the first two newspapers were easy to find in the cabinets. Microfilm takes some patience, especially when trying to move through a lot of data at once. For example, the tape for The American Volunteer began with the 1833 editions, but I didn’t intend on using any issues published before 1838. As such, I was overjoyed to find a button on the reader’s interface which fast-forwards the film without the user having to keep their finger on the button, allowing me to do further research while the tape wound.

During one of these breaks I decided to finally uncover more about the mysterious Locofoco party, which I had never encountered in my earlier education but whose name had appeared multiple times in my reading. After a quick search in the Dickinson Online Databases, I found an article by Carl N. Degler, a history professor at Vassar, entitled “The Locofocos: Urban ‘Agrarians.’”[1] From this piece I learned that the Locofocos were a faction of the Democratic party which aimed to curry favor with the poor and pulled from the same voting groups as Democratic president Andrew Jackson.

Step Three: The Expositor

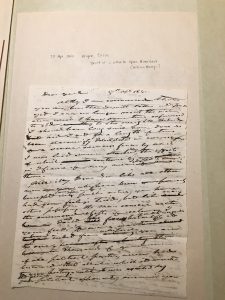

With this information in mind and the microfilm finally wound to the correct year, I looked first at the May 1, 1838 edition of The Carlisle Herald and Expositor. This newspaper was far more clearly organized than some others of its time, and I was thrilled to find that it had in fact a whole column dedicated to political issues[2]. On this date, some time before the presidential election, the paper instead covered the upcoming 1838 gubernatorial election in Pennsylvania. It was a point-by-point takedown of Democratic candidate David R. Porter and, while it said little about the nature of the presidential election to come, it did establish the Expositor as a solidly Whig-leaning paper and laid out the views of Whig Carlilians of the time. Far more telling than the first headline which caught my eye was in fact an advertisement[3] on the second page which clearly endorsed the Whig William Henry Harrison for president fully two years before the election. The seemingly interminable election cycle which repeats itself every four years in the United States has been oft-bemoaned as tiring and unnecessary, so it was interesting to see its roots as far back as 1838.

Intrigued by what I had found in the Expositor, I attempted to do more outside research on these small tickets, which my professor informed me could actually be used as ballots. Starting with a broad google search, I combined many term clusters such as “william henry harrison,” “newspaper,” “ballots,” and “1840 voting system.” I didn’t find very much about the ballots, but I did discover that the campaigns actually each had their own newspapers in addition to the already partisan local weeklies, so I would be eager as a I continue my research to explore these documents further and investigate how they influenced the election.

Moving forward, I skipped to the next year’s issues and found an article entitled “The Next President”[4] on page two of the May 8, 1839 edition. At this point, the gubernatorial election had still not taken place: the paper continued to endorse incumbent Anti-Masonic Joseph Ritner. Their man would go on to lose to Democrat David R. Porter whom the paper had so lambasted the previous May, but at the time of printing the paper was eagerly awaiting Ritner’s re-election, predicting that the Democratic party would “sink forever, with its misdeeds.”4By the time of this publication, with the presidential election about a year and a half away, the Expositor wished to focus on the task at hand: “We go first for the re-election of Joseph Ritner–Then we go for General Harrison…because we belive [sic] him to be the most available candidate for Pennsylvania.”4 These mentions of the presidential race so long before it actually occurred show how this was to be a different game altogether, but only with further research will I uncover how the newspapers handled the campaign itself.

Step Four: The Volunteer

Though I will be sure to return to the later issues of the Expositor, during this first visit to the microfilm machine I was eager to see another political point of view. To that end I next fed in the reel for The American Volunteer, a Democratic paper which covered a “Great Democratic Meeting”[5] on October 8, 1837. This issue was also discussing the gubernatorial election, an event which seems to have sown the seeds of inter-party animosity in Pennsylvania leading up to the polarizing 1840 presidential election. The Volunteer saw the gravity of the situation and described the battle to come: “We are on the eve of an election of the most important character; an election in which the question whether the people or a local aristocracy will rule.”5Having seen how the local writers of both parties viewed one another before the presidential election, I am anxious to visit the Cumberland County archives to see later articles and determine how they dealt with the unique campaign and eventual result.

Footnotes:

[1] Carl N. Degler, “The Locofocos: Urban ‘Agrarians,’” The Journal of Economic History, 16, no. 3 (1956): 322-333

[2] The Carlisle Herald and Expositor (Carlisle, PA), May 1, 1838, pg 1 col. 7

[3] The Carlisle Herald and Expositor (Carlisle, PA), May 1, 1838, pg 2 col. 6

[4] The Carlisle Herald and Expositor (Carlisle, PA), May 8, 1839, pg 2 col. 7

[5] The American Volunteer (Carlisle, PA), October 8, 1837, pg 1 col. 4