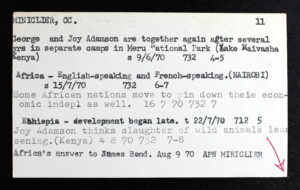

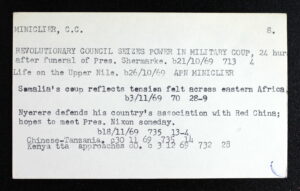

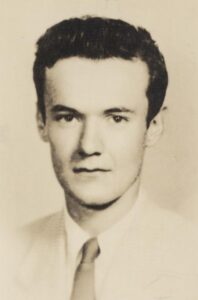

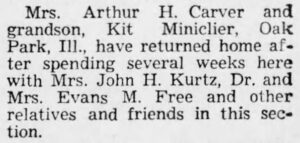

The coolest primary source find I came across while researching Christopher Miniclier ’57 was the Associated Press Name/Subject Card index, which organized the articles AP authors had written by date under their author. It was the key to figuring out Miniclier’s story. Reading through the article titles alone is enough to get an idea of what he experienced, but its research value is so much more than that.

It was a real cipher, both in the sense that it was like a code and in the sense that it symbolized his impact on the public perception of events. I decided to look deeper into the index as a case study of historical research: what did they represent? who saw them? what did they not say? what contradictions could they give up? More importantly, what conclusions could I draw from my analysis of them? (And most importantly, how much could I work on the project at the same time as doing research for my thesis?)

Being an index, the cards did not tell me nearly enough information to tell what was going on when Miniclier was writing his articles; they could only point me to other things. While I was organizing my database of evidence, I had to do some on-the-fly historical research: many of the titles in his Name/Subject index cards contained names with which I was unfamiliar. He had spent seven years as a foreign correspondent in Northern Africa and the Middle East in the late 1960s/early 1970s, and he’d written about coups, wars, tenuous alliances, drought and political assassinations—there was a lot going on.

Conclusion #1: The cards didn’t have all the information I needed to understand their full value. But that much was obvious. They did, on the other hand, often hint just enough at something that I could either look up the article in a newspaper database or look up the figures, places and events the subject titles referenced.

For example, Miniclier wrote several articles about George and Joy Adamson, who were European wildlife conservationists in Kenya. Both would later be murdered.1

I wanted to see what I could learn about Miniclier’s job as a reporter in general and a foreign correspondent in particular, so I used JumpStart to find some sources related to the Associated Press and foreign correspondents. Some parts of Ulf Hannerz’s Foreign News: Exploring the World of Foreign Correspondents were not relevant to my research, because they dealt with a later time period, but one passage particularly struck me:

On New Year’s Eve 2001, Leif Norrman (2001), in Cape Town, had a reflective piece in Dagens Nyheter, occasioned by a telephone call he had received from a young woman from a Swedish radio station. She was doing a program on foreign correspondent life (I was also on it) and asked him how his experience compared to that of foreign correspondents in the movies. He felt a bit embarrassed because it was not much like that. […] Yes, there were times of fright, and uncertainty, and the stench of dead bodies. But the most destructive part of a correspondent’s everyday life, he concluded, was emptiness: the emptiness that comes when one’s beat is out of focus, when nobody seems to care what happens there.2

The burden to “represent groups to spectators” who are quite far away is a heavy one.3 And as Hannerz points out, these representations often have to compete for primacy in the public sphere, shared by a public that may be interested in the goings-on around the correspondent, but not necessarily more so than they are the goings-on around themselves.4 Hannerz (and Norrman) articulate a tension between “communication” and “publicity,” where communication—what the foreign correspondent may wish to engage in—involves a transmission of information, and publicity involves a sense of shared spectatorship.5

This aspect of publicity is effected by the newspaper medium, which visibly and invisibly links acquaintances and strangers alike by creating “a collectivity consisting of strangers who realize each other as the spectators of the same thing,” because newspapers, and the “pieces” of news they contain, are understood to be distributed among the public.6

Conclusion #2: The index represents not just Miniclier’s story but an impression of his audience (including the AP) and their impact on him; it is the story of a negotiation between their expectations and his work.

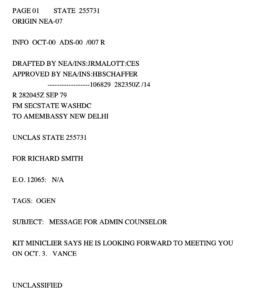

Skimming through the two databases that list articles Miniclier wrote—the Associated Press Name/Subject card index and Newspapers.com—I noticed that many of the articles I was finding in the newspapers were not the same ones listed in the AP index. Most of the ones listed in the AP index were published without a byline that named Miniclier, instead giving the location (“Nairobi, Kenya (AP)”). The hiddenness of the author contributes to the publicity of whatever event the article describes, and it obfuscates any personal bias or subjectivity on the part of the author.

Yet, some people obviously knew which articles Miniclier had written. The AP Name/Subject Card index, then, is the site of a power differential between the author (Miniclier), the Associated Press and the two groups—his countrymen/reading public and the people he wrote about—for which Miniclier was, in a way, responsible.7 It is a removed site, placed out of reach of the general public, and even out of reach to those who have access to archival databases, because deciphering the story still requires effort. Removed sites, though, are still accessible.

Conclusion #3: The index disrupts the publicity/passive spectacle of current events/history built up by the uncredited AP articles by assigning subjects to their authors, grouping titles together by author and date to create a subjective narrative.

That’s what the work of history is about: it’s the grouping of facts that counts more than the finding.

If journalists manipulate time, lists that put the events journalists write about right next to each other condense it even further, creating a strange temporality.8 Events just keep on happening. Or, if one pays attention to the dates next to each subject listed in the index, sometimes there are gaps between articles that last months. Did nothing happen? Were the events put on hold for a bit? Because newspapers report on things of note, descriptions of the everyday are likely to be only incidental to setting the scene.

The subject lines for 1971-74, during which years Miniclier was in Egypt, reference the 1973 war between Egypt and Israel. They don’t mention what was doubtless another topic of much discussion among the residents of Cairo: the monthly radio concerts by Egyptian singer Umm Kulthum that were broadcast all over the Arab world, and that singer’s illness and death in the latter half of Miniclier’s stay.9 Did Miniclier and his family listen to these concerts? How immersed were they in the culture of the countries he reported on? The articles don’t tell us very much.

Conclusion #4: By grouping together all the articles in a (relatively) full list, the index betrays what storylines were privileged over others, and gestures toward the ways public perception is shaped by the intersection of political agendas.

I knew Miniclier’s time as a correspondent had to have been characterized by the Cold War. Although he was not near Vietnam, he probably felt its impact as a journalist: the New York Times and the Washington Post published the “Pentagon Papers,” documents about that war, in 1971, in a move that declared their control of public information against government interests.10

That wasn’t the first time a news company had used news as leverage or as property. Miniclier himself was employed by one of the organizations that worked to “establish control over news reports through contracts that excluded other providers,” a strategy that “shaped the business of news and competition” and put the investigation and dissemination of information firmly under the yoke of capital.11

Conclusion #5: Even if certain storylines are privileged over others, the index reminds us researchers to be compassionate to the author of the source and to consider all nuances, no matter what the storyline is.

[1] “Joy Adamson,” Britannica Academic, Accessed April 3, 2023, https://academic.eb.com/levels/collegiate/article/Joy-Adamson/485.

[2] Ulf Hannerz and Anthony T. Carter, Foreign News: Exploring the World of Foreign Correspondents (Chicago: University of Chicago Press), 213.

[3] Ari Adut, “A Theory of the Public Sphere,” Sociological Theory 30, No. 4 (December 2012): 244.

[4] Hannerz, 213.

[5] Adut, 244.

[6] Adut, 244.

[7] James L. Baughman, “The Decline of Journalism Since 1945,” in Making News: the Political Economy of Journalism in Britain and America from the Glorious Revolution to the Internet, ed. Richard R. John and Jonathan Silberstein-Loeb, first edition (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015), 169.

[8] Hannerz, 208.

[9] Virginia Danielson, “The Voice of Egypt”: Umm Kulthūm, Arabic Song, and Egyptian Society in the Twentieth Century (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1997), 1.

[10] Baughman, 169.

[11] Heidi J. S. Tworek, “Protecting News Before the Internet,” in Making News: the Political Economy of Journalism in Britain and America from the Glorious Revolution to the Internet, ed. Richard R. John and Jonathan Silberstein-Loeb, first edition (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015), 198.

Bibliography

Adut, Ari. “A Theory of the Public Sphere.” Sociological Theory 30, No. 4 (December 2012): 238-262. [JSTOR]

Associated Press File Drawers of National, International, News Feature Name/Subject Cards, 1937–1985. Microfilm, 1114-1154. Associated Press Corporate Archives, New York, NY. [Ancestry.com]

Baughman, James L. “The Decline of Journalism Since 1945.” In Making News: the Political Economy of Journalism in Britain and America from the Glorious Revolution to the Internet. Edited by Richard R. John and Jonathan Silberstein-Loeb. First edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015. [EBSCO]

Danielson, Virginia. “The Voice of Egypt”: Umm Kulthūm, Arabic Song, and Egyptian Society in the Twentieth Century. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1997.

Hannerz, Ulf, and Anthony T. Carter. Foreign News: Exploring the World of Foreign Correspondents. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004. [ProQuest]

“Joy Adamson.” Britannica Academic. Accessed April 3, 2023. https://academic.eb.com/levels/collegiate/article/Joy-Adamson/485. [BRITANNICA ACADEMIC]

Tworek, Heidi J. S. “Protecting News Before the Internet.” In Making News: the Political Economy of Journalism in Britain and America from the Glorious Revolution to the Internet. Edited by Richard R. John and Jonathan Silberstein-Loeb. First edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015. [EBSCO]