If you’ve never found yourself immersed in the world of academic book reviews, you would probably assume that they are all boring, apathetic, criticisms of other boring, apathetic volumes. I was apt to think the same at first, but after reading more than fifty reviews from The Journal of American History (March 2018), I realize that they have a style of their own and forcing upon them the expectations of pop culture reviews is not only unfair but also misses the nuance and elegance of the academic historian’s book review.

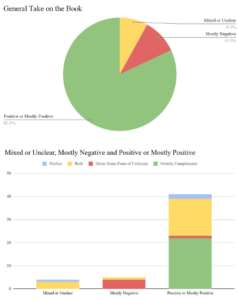

Firstly, not all of the reviews are negative. In fact, most are positive. Eighty-two percent of the reviews I looked at for this project were positive or at least mostly positive. This is not to say that they aren’t critical in some way: twenty-two percent of reviews criticized the writing and thirty-eight percent pointed out a gap in the historical narrative of the book in question. Roughly two-thirds of the reviews with either or both forms of negative criticism were still overall positive reviews. Often the reviewers use the criticism to emphasize how impressive another aspect of the work is. One reviewer noted that a work had “more typographical errors than a reader can ignore, but [that] it has much to teach about the New Negro movement.”[1] To say a work “has much to teach” seems kind, but bland. To say a work is a typographical mess but is still more than worth reading is far higher praise and better prepares the audience for what they are about to encounter.

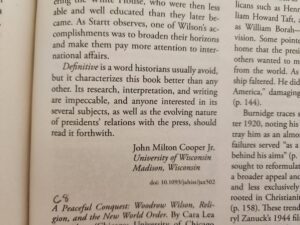

As for apathy: I heartily deny its existence. I thought the tone was cold, until I came to John Milton Cooper Jr.’s review of James D. Startt’s Woodrow Wilson, the Great War, and the Fourth Estate (2017). In the final paragraph he says “Definitive is a word historians usually avoid, but it characterizes this book better than any other.”[2] Definitive is not a word you would likely use to describe your favorite book or movie, certainly not a word you would use to compliment a friend, a good meal, or most things you generally find yourself applauding. For Cooper, though, he is bestowing some of the most incredible praise. He is saying that the book addresses all the relevant topics, is well researched and well written, draws appropriate conclusions, and overall contains all the information one wants or needs on that topic. Definitive doesn’t sound warm and fuzzy, but in context, it is the warmest praise possible.

With that realization, I looked back at the other compliments and commentaries. Compliments were seldom about how interesting a volume or topic was, with only twelve percent calling something interesting, or more often “fascinating,” despite eighty percent of reviews giving some form of praise.[3] Most compliments emphasized what the author did that was impressive be it “…meticulous and revelatory archival work,” or writing in an “enticing” or “accessible” style.[4] In the same way critiques focus on what the authors neglected, such as paying “inadequate attention to racial differences” or leaving questions unanswered.[5]

From this we see what reviewers value. Different reviewers prefer different styles of writing; different books have different goals. However, all historians share certain values as they recognize the effort that goes into research and writing and the importance of accuracy and honesty in these endeavors. In The Princeton Guide to Historical Research (2021), Zachary Schrag identifies these values as curiosity, accuracy, judgement, empathy, gratitude, and truth.[6]

These values are why reviewers write reviews with the book open in front of them, taking the time to quote the authors and often other scholarship on the same topic as well. Its why reviewers don’t write streams of accolades for the books, even when they really enjoyed reading them: they want to describe what the author did and let that stand as praise in and of itself. A good volume of history answers questions and brings to light new information and understanding—it strives to be definitive, to analyze all the aspects of a topic with the evidence to support that analysis. When a volume cannot be definitive, it seeks to build a strong foundation for future research or to add new perspectives to a topic that has yet to be fully fleshed out.[7] Reviews outline a volume’s success in this endeavor. The reviewer acknowledges the work of previous historians and shows where this work diverges and treads new ground. They show why the work is worth reading by showing the curiosity of its author, the accuracy of their research, the truths they bring to light. What looks like just a two-page summary can just as easily be read as a two-page list of achievements. That hardly sounds cold or apathetic.

So now I have only “boring” to disprove. Unfortunately, “boring,” being subjective, is difficult to disprove. Book reviews have a specific purpose: to describe a book and what it’s about, what it does, who it’s for, how it’s written, etc. The reviews are most often written by and for academics. They are meant to be informative, not entertaining, so, no, they are not particularly riveting, but that does not necessarily make them “boring.” It just means that they should be read in context.

If you were looking for a good book on equal rights and the Declaration of independence, the title and Michal Yan Rozbicki’s first line on Richard D. Brown’s Self-Evident Truths (2017) would tell you plenty: it “is a rewarding volume—carefully written, balanced, and well documented.”[8] However, if you stopped there, you would never know how passionate and excited about the book Rozbicki really was. You would miss the way he describes the arguments of the work and highlights the complexities within it—the subtlety with which one historian tips his hat to another, recognizing his colleague’s hard work. You would miss the real art of a book review.

Evangeline Clausson, 2/10/2025

[1] Koritha Mitchell, review of Colored No More: Reinventing Black Womanhood in Washington, D.C. by Treva B. Lindsey, Journal of American History 104, no. 4 (March 2018): 1031.

[2] John Milton Cooper Jr., review of Woodrow Wilson, the Great War, and the Fourth Estate by James D. Startt, Journal of American History 104, no. 4 (March 2018): 1050-1.

[3] Ashley Carse, review of Water: Abundance, Scarcity, and Security in the Age of Humanity by Jeremy J. Schmidt, Journal of American History 104, no. 4 (March 2018): 995.

Mitchell, review of Colored No More, 1031.

[4] Kimberly Johnson, review of States of Dependency: Welfare, Rights, and American Governance, 1935-1972 by Karen Tani, Journal of American History 104, no. 4 (March 2018): 1082.

Etsuko Taketani, review of Strange Fruit of the Black Pacific: Imperialism’s Racial Justice and Its Fugitives by Vince Schleitwiler, Journal of American History 104, no. 4 (March 2018): 1045-6.

Lane Demas, review of Separate Games: African American Sport behind the Walls of Segregation, Ed. by David K. Wiggins and Ryan A. Swanson, Journal of American History 104, no. 4 (March 2018): 1054-5.

[5] Sarah E. Chinn, review of Get Out of My Room! A History of Teen Bedrooms in America by Jason Reid, Journal of American History 104, no. 4 (March 2018): 1041-2.

Anders Stephanson, review of Understanding and Teaching the Cold War Ed. by Matthew Masur, Journal of American History 104, no. 4 (March 2018): 994.

[6] Zachary M. Schrag, The Princeton Guide to Historical Research (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2021), 24-36. [JSTOR].

[7] Schrag, Princeton Guide: 90-1 [JSTOR].

[8] Michal Jan Rozbicki, review of Self-Evident Truths: Contesting Equal Rights from the Revolution to the Civil War by Richard D. Brown, Journal of American History 104, no. 4 (March 2018): 1014.