“Twenty-four hours from the present writing the question will have been settled who is to be the President of the United States for four years from March 4, but during the interval between this time and that, when the result will be known, the American people will be in a state of excited expectancy.”

–National Republican, Nov. 7, 1876

When Republican Rutherford B. Hayes and his wife Lucy went to bed on the night of Tuesday, November 7, 1876, Hayes was resigned to the fact that he had lost the 19th presidential election. By midnight, the Democratic candidate, Samuel J. Tilden, was ahead by about 225,000 popular votes, with over 8.2 million votes cast. He was leading in the electoral vote with 184 out of the required 185 votes to secure the presidency,[1] and the Democrats were eager to pack their bags, evict the Republicans, and occupy the White House for the first time in 15 years. [2] Hayes stayed up to wait on returns from swing state New York, which he and advisors thought would decide the election. When a dispatch sent word that Tilden had a 50,000 vote lead in New York City, Hayes wrote, “from that point, I never supposed there was a chance for Republican success.” Rutherford Hayes wrote in his diary that night, “we soon fell into a refreshing sleep (…) and the affair seemed over.” [3]

19th President, 1877-1881. Courtesy of The White House, https://www.whitehouse.gov/1600/presidents/rutherfordbhayes.

However, within a few hours, controversial vote tallies came in from four states. Both the Democrats and the Republicans accused each other of fraudulent voting practices and a fierce battle for the presidency ensued, but predominantly between Democrat and Republican Party leaders and not between Hayes and Tilden themselves. With a reputation as an honest man, Hayes did not immediately contest the election, being more worried about the legitimacy of recounting the votes than winning. [4] Although Rutherford B. Hayes remained uninvolved in the election day voting fraud and subsequent recounts, both Republican Party leaders and Democrat leaders revealed intense party competition and corruption of the time period by prioritizing an 1876 party win over a just democratic election, and challenging the right to a fair vote.

While Hayes slept, convinced of his defeat, former Republican congressman Daniel Sickles, stopped at the Republican headquarters to check on the voting return numbers. He quickly realized that if Hayes secured the seven electoral votes from South Carolina, eight electoral votes from Louisiana, and four electoral votes from Florida, all of which had not come in yet, then Hayes’ count would increase from 165 to tie Tilden at 184. Seeing Zachariah Chandler, the Republican Party chairman, in a drunken stupor in his office, Sickles decided to send telegrams in Chandler’s name to several Republican leaders in South Carolina, Louisiana, and Florida to alert them of the importance of those states’ electoral votes. He received reply, “All right. South Carolina is for Hayes” from Governor Daniel Chamberlain at 3:00 am. [5] Sickles’ dishonesty marked the beginning of a duplicitous election day, although without his telegrams, Hayes may have had no chance at winning.

When Hayes awoke on the 8th, he wrote a letter to his son at Cornell reflecting on his loss. He graciously accepted the outcome, but was disappointed in not having a chance “to establish Civil Service reform, and to do good work for the South” as part of his campaign platform. [6] Both presidential candidates were popular because of their integrity and desire for reform. Hayes, the governor of Ohio, had supported Reconstruction efforts and the ratification of the 15th Amendment, and he wanted to continue to improve the conditions of African Americans in the South. He didn’t smoke, he didn’t drink, and was a volunteer during the Civil War. His opponent, Tilden, was the governor of New York, and known for helping to dissolve the corrupt Tweed Ring Democrat group. Both Hayes and Tilden were appealing presidential figures who contrasted President Grant’s administration, which was tainted with bribery and scandal. Ironically, the election day proceedings did not meet the virtuous standards of its candidates. [7]

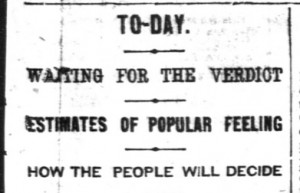

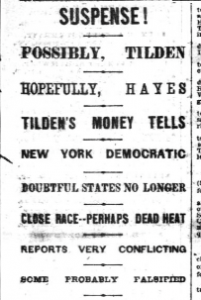

Not long after writing the letter to his son, Hayes was informed that he had won the West Coast and could still win the election. As the sun rose that morning, the president-elect was undetermined, and copies of the National Republican circulated in Washington DC shouting the headline, “Suspense! Possibly Tilden, Hopefully Hayes (…) Reports Very Conflicting, Some Probably Falsified.” [8] The hesitation in declaring a president-elect was due to inconsistent popular vote counts in South Carolina, Louisiana, and Florida, as well as a questionable electoral voter in Oregon. In the 1870s, voting ballots were actually “party tickets,” printed by political parties and containing a list of all candidates for that party. They might have been printed in a color to represent the party and to aid illiterate voters. These tickets made voting fraud simple, as multiple tickets could easily be folded up and submitted by one person. [9] In addition, Hayes believed that the election had been stolen from him through unconstitutional voting restrictions in the South, primarily through limiting African Americans’ and white republicans’ ability to vote by racist terrorist groups and registration requirements, but he was prepared to “accept the inevitable” with “composure and cheerfulness.” [10]

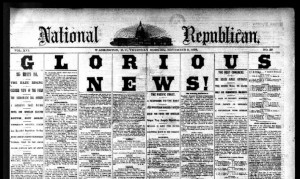

Both parties certain that they had won the states, they each submitted separate vote tallies to Congress. In Florida, out of 47,000 votes, Republicans reported a 922 vote margin with Hayes ahead, and denounced the Democrats for restricting African Americans’ voting rights through intimidation tactics and bribery [11] in addition to tricking illiterate voters by printing Democratic ballots with a Republican symbol. [12] So convinced that they had won the election, by November 9, the Republican newspaper National Republican proclaimed that Hayes had won with the full page headline “Glorious News!” [13]

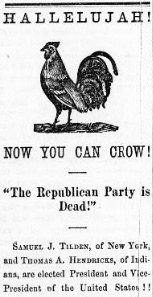

On the other hand, Democrats were just as confident that Tilden was the winner. In Florida, they claimed that there was a 94 vote margin in favor of Tilden, and contended that Republicans had smeared ink on ballots in a pro-Tilden county to discredit those votes. [14] Voting officials accused opposing parties of stuffing ballot boxes with false votes, and that in some counties, the number of votes surpassed population. To add to the already high level of deception, allegedly the Democratic National Committee in LA claimed that the Republicans suggested that there would be a guaranteed Democratic popular majority in exchange for $1 million. [15] In Oregon, the Democrat Governor La Fayette Grover noticed that one of the Republican electors was federally employed at a post office, and therefore ineligible to be an elector. He appointed a new Democrat elector, and although Hayes still won the electoral votes for Oregon, the Democrats responded by crying fraud. [16] In Louisiana, citizens were informed that Democrats won the election. A Democrat newspaper, the Louisiana Democrat, printed on November 15, “The Republican Party is Dead!” in celebration of a Tilden majority. [17] A week after election day, inconsistent reports announced either Hayes or Tilden as the president-elect, and both parties unequivocally advocated for their own candidate.

The level of cheating on both sides was undoubtedly high. To attempt to reach a verdict, Republican officials under Grant set up “returning boards” in South Carolina, Louisiana, and Florida to recount disputed votes. Besides sorting through problems related to voter activity, bribery, and other depravities, there was the issue of how to count the controversial votes. Hayes told friend US Senator Carl Schurz that he was concerned that “in the canvassing of results there should be no taint of dishonesty,” and wrote to John Sherman, who was a Republican statesman dispatched to Louisiana, “we are not to allow our friends to defeat one outrage and fraud by another…there must be nothing crooked on our part.” [18] Hayes was dismayed at the amount of underhanded political dealing contributing to the election, and acknowledged that the democracy set up by the Founding Fathers was failing; he wrote in his diary on December 7, 1876, “A contest ruinous to the country, dangerous, perhaps fatal to free government may grow out of [the fraud]. I would gladly give up all claim to the [presidency], if this would avert the evil without bringing on us a greater calamity.” [19] Hayes soon realized that his protests were in vain; party leaders were determined to amass as many votes as possible and the Republican Party was adamant about winning the election by any means necessary.

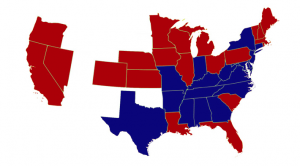

Map of Electoral Votes in 1876 Presidential Election. Red represents votes for Hayes and blue represents votes for Tilden. Courtesy of the American Presidency Project.

Not until 4:10 am on March 2, 1877 was election day truly over. [20] Ultimately, Rutherford Hayes won the election. Republican candidates Hayes and running mate William Wheeler were given 4,033,497 popular votes, or 48%, and 185 electoral votes. Democrats Tilden and Hendricks were given 4,288,191 popular votes, or 51%, and 184 electoral votes. In spite of losing the popular vote, all disputed electoral votes from South Carolina, Louisiana, Florida, and Oregon were awarded to Hayes. [21]

Fraudulent votes and political party intervention at the state level corrupted the election and made it effectively impossible to determine a true winner, and Democrats started calling Hayes “Rutherfraud” and “His Fraudulency” because they were furious at how he “stole” the election. [22] Hayes expressed in his inaugural speech on March 5 that he, “owed his election to office to the…zealous labors of a political party” because it was due to the interventions of his party’s supporters that he was eventually elected. [23] The election day events of 1876 exposed the democratic-republican government experiment as an imperfect system. The election demonstrated that election day voting needed continual adjustment to avoid biased votes and false votes from political parties, and set the stage for later constitutional debates over the right to vote and the right to have a vote counted.

[1] Richard Wormser, “Hayes-Tilden Election (1876),” The Rise and Fall of Jim Crow, PBS, 2002. Retrieved Oct. 30, 2016 from http://www.pbs.org/wnet/jimcrow/stories_events_election.html

[2] S. Mintz and S. McNeil, “The Disputed Presidential Election of 1876,” Digital History, 2016. Retrieved Oct. 30, 2016 from

http://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/disp_textbook.cfm?smtID=2&psid=3109.

[3] Rutherford B. Hayes, Diary of Rutherford B. Hayes, Volume III, The Disputed Election–Electoral Commission–Selection of Cabinet, 1876-1877, Nov. 11, 1876, Ohio History Connection. Retrieved Nov. 4, 2016 from http://apps.ohiohistory.org/hayes/results.php?page=4&ipp=20&&searchterm=election

[4] Ari Hoogenboom, “Chapter 17: Disputed Election,” Rutherford B. Hayes: Warrior & President (University Press of Kansas, 1995). Retrieved Oct. 30, 2016 from http://www.rbhayes.org/hayes/disputed-election-by-ari-hoogenboom/

[5] “The Political Situation,” Finding Precedent: Hayes vs Tilden, HarpWeek, 2008. Retrieved Oct. 30, 2016 from http://elections.harpweek.com/09Ver2Controversy/Overview-1.htm.

[6] Rowland L. Young, “The Year They Stole the White House,” ABA Journal 62 (1976): 1460. [Google Books]

[7] Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. “Rutherford B. Hayes: Campaigns and Elections.” Miller Center. Accessed Oct. 30, 2016 from http://millercenter.org/president/biography/hayes-campaigns-and-elections

[8] The National Republican, (Washington DC), Nov. 8, 1876. [Library of Congress] Retrieved Oct. 30, 2016 from http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn86053573/1876-11-08/ed-1/seq-1/

[9] “The History of the Paper Ballot,” Fair Vote. Retrieved Oct. 30, 2016 from http://archive.fairvote.org/righttovote/pballot.pdf

[10] Rutherford B. Hayes, Diary of Rutherford B. Hayes, Volume III, The Disputed Election–Electoral Commission–Selection of Cabinet, 1876-1877, Nov. 12, 1876, Ohio History Connection. Retrieved Nov. 4, 2016 from http://apps.ohiohistory.org/hayes/results.php?page=4&ipp=20&&searchterm=election

[11] S. Mintz and S. McNeil, “The Disputed Presidential Election of 1876,” Digital History, 2016. Retrieved Oct. 30, 2016 from

http://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/disp_textbook.cfm?smtID=2&psid=3109.

[12] Ari Hoogenboom, “Chapter 17: Disputed Election,” Rutherford B. Hayes: Warrior & President (University Press of Kansas, 1995). Retrieved Oct. 30, 2016 from http://www.rbhayes.org/hayes/disputed-election-by-ari-hoogenboom/

[13] The National Republican (Washington DC), Nov. 9, 1876. [Library of Congress] Retrieved Nov. 6. 2016 from http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn86053573/1876-11-09/ed-1/seq-1/.

[14] S. Mintz and S. McNeil, “The Disputed Presidential Election of 1876,” Digital History, 2016. Retrieved Oct. 30, 2016 from

http://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/disp_textbook.cfm?smtID=2&psid=3109.

[15] Gilbert King, “The Ugliest, Most Contentious Presidential Election Ever,” Smithsonian.com, Sept. 7, 2012. Retrieved Oct. 30, 2016 from http://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/the-ugliest-most-contentious-presidential-election-ever-28429530/?no-ist.

[16] S. Mintz and S. McNeil, “The Disputed Presidential Election of 1876,” Digital History, 2016. Retrieved Oct. 30, 2016 from

http://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/disp_textbook.cfm?smtID=2&psid=3109.

[17] The Louisiana Democrat [Alexandria, LA], Nov. 15, 1876. [Library of Congress] Retrieved Nov. 6, 2016 from http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82003389/1876-11-15/ed-1/seq-2/.

[18] Quotes in Ari Hoogenboom, “Chapter 17: Disputed Election,” Rutherford B. Hayes: Warrior & President (University Press of Kansas, 1995). Retrieved Oct. 30, 2016 from http://www.rbhayes.org/hayes/disputed-election-by-ari-hoogenboom/

[19] Rutherford B. Hayes, Diary of Rutherford B. Hayes, Volume III, The Disputed Election–Electoral Commission–Selection of Cabinet, 1876-1877, Dec. 7, 1876, Ohio History Connection. Retrieved Nov. 1, 2016 from http://apps.ohiohistory.org/hayes/results.php?page=5&ipp=20&&searchterm=election

[20] Ari Hoogenboom, “Chapter 17: Disputed Election,” Rutherford B. Hayes: Warrior & President (University Press of Kansas, 1995). Retrieved Oct. 30, 2016 from http://www.rbhayes.org/hayes/disputed-election-by-ari-hoogenboom/

[21] John Woolley and Gerhard Peters, “Election of 1876,” The American Presidency Project, 2016. Retrieved Nov. 1, 2016 from http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/showelection.php?year=1876

[22] Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. “Rutherford B. Hayes: Campaigns and Elections.” Miller Center. Accessed Oct. 30, 2016 from http://millercenter.org/president/biography/hayes-campaigns-and-elections

[23] Rutherford B. Hayes, “Inaugural Address of Rutherford B. Hayes,” March 5, 1877. Yale Law School Lillian Goldman Law Library, 2014. Retrieved Nov. 1, 2016 from http://avalon.law.yale.edu/19th_century/hayes.asp

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.