The 1948 election presented a new opportunity for the United States. After Franklin Roosevelt had won four consecutive elections, there was now a clean slate, so to speak, and not just with two major party candidates. While Democrat Harry Truman and Republican Thomas Dewey (and to a lesser extent Dixiecrat Strom Thurmond and Progressive Henry Wallace) vied for the country’s future, a well-known American political custom was falling apart.

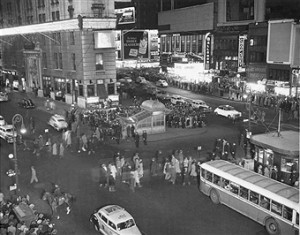

In the November 3rd New York Times Meyer Berger wrote, “Times Square saw the death of a tradition yesterday. For the first time on a national election night, the Square was comparatively thinly populated. Such crowds as did assemble were voiceless, and without spirit.”[1] While the forecast had cooperated, described as “just enough nip in the night wind with the mercury in the forties”[2] the crowds “never did more than mutter or utter the weakest of cheers.”[3] The new election could have presented the public an opportunity to usher in a new American era but instead it was nothing more than a footnote in the story of the election. Berger wrote “Veteran election night observers seemed inclined to attribute the decline in open-air election night celebrations to the fact that more and more persons take their returns over the radio and over television. They figured the holiday tradition on election night is about dead.”[4] With the growing influence that media played on the American public, something FDR had helped usher in with his fireside chats, Truman’s victory celebrations were confined to private residences. However the crowd in the center of New York had chosen a candidate. The attitudes were described as “What noise there was—and it was never more than a murmur—seemed to be for President Truman. A few horn blasts heard around midnight, the one brief flurry of confetti at the same time came at announcement of the President’s lead.”[5]

The above description shows the beginning of a shift in American politics. As the culture changed from mass events and gatherings to smaller, more private gatherings in households the country was shifting in general. Moving on, past FDR itself brought new challenges, as Truman’s victory and continuance of his predecessor’s policies was uncertain. Instead Thomas Dewey or Strom Thurmond or Henry Wallace could bring about change that the U.S. hadn’t seen in 16 years. However the ideas of change also created negative kinds of uncertainty. On the actual Election Day only 53% of the population came out to vote, the lowest since 1924 (and would be the lowest until 1980)[6]. The combination of low voter turnout and shifts in American attitudes about how to view the election created the scene described in Times Square, a scene that Berger painted as a disappointment about a dying tradition. The election itself and the reaction created a pivotal election in American history, even if the victor and victory was the least pivotal aspect.

Of course, the election of 1948 is best known for the botched Chicago Daily Tribune headline “Dewey Defeats Truman” that was released well before the actual returns. The photo went on to become the sole image that most people remember from the election. In his book Battleground 1948: Truman, Stevenson, Douglas, and the Most Surprising Election in Illinois History Robert Hartley wrote “Truman’s upset victory stunned the nation, as it still does today. He received a little less than 50 percent of the popular vote to 45 percent for Dewey, 2 percent for Strom Thurmond, and 2 percent for Henry Wallace.”[7] When describing what Truman did during the election, Philip White wrote, “Now on November 2, after giving his all, there was nothing more he could do. He had spoken his mind, in his own way, at every stop, whether addressing eighty thousand people at the National Plowing Match or a handful at one of the many stations well off the main line. If his efforts had been sufficient to pull off the unlikeliest of comebacks he would be delighted”.[8] The idea of Truman simply being forced to wait around is not unlike what many of his supporters did in Times Square the night of his election. The uncertainty in the election itself contributed to the idea that Truman had done all that he could. Gone were the opportunities to reach out to voters and instead Truman had to wait for “a few horn blasts” and a “brief flurry of confetti.”[9] However while waiting, instead of standing outside Truman rested “taking a Turkish bath and then consuming a supper that was as straightforward as the man himself: a ham and cheese sandwich and glass of buttermilk. He then retired for the evening at 9:00 p.m., the earliest bedtime he had allowed himself in months.”[10] In an interesting urn of events, Truman himself represented the shift in American culture. The president himself brought forward the new idea of staying inside on election night. Instead of even what current day candidates do, throwing elaborate Election Day parties, Truman chose to remain solitary and removed. There is no coincidence that most of the American people also chose to stay out of any possible limelight.

Those who were actually in Times Square in early November 1948 still had a lot to say about the election, even if en masse they were silent. One old man said “These political experts, they’re like the weatherman. The weatherman predicted rain tonight and the political experts picked Dewey. There’s no rain and it looks like it might not even be dewy.”[11] As Times Square was deflated, a few streets over in Rockefeller Plaza the old Election Night festivities were getting a facelift. Much of the crowd to seems to have migrated to the Rock as “almost 5,000 persons assembled to watch the results as shown on a screen 15×20 feet. Images of the candidates in action, and of nation-wide returns were shown. It was an improvement on Election Night in the old tradition.”[12] The shift away from mass movements to watch the election was not yet complete as changing technology also improved the large-scale watch parties. Even with the crowd in Rockefeller Center, the lack of enthusiasm in Times Square was a larger indication of American’s attitude change. Slowly more and more of the public began to replicate President Truman’s Election Day plan of staying inside, an attitude that still defines how the country views the voting results.

[1] Meyer Berger, “Election Night Crowd in Times Sq. Is Thin, Silent and Without Spirit.” New York Times (New York, NY), Nov. 3, 1948

[2] Berger

[3] Berger

[4] Berger

[5] Berger

[6] The American Presidency Project

[7] Robert Hartley, Battleground 1948: Truman, Stevenson, Douglas, and the Most Surprising Election in Illinois History (Southern Illinois University Press, 2013) 194.

[8] Philip White, The Election of 1948 (ForeEdge, 2014) 236.

[9] Berger

[10] White 237.

[11] Berger

[12] Berger